Image description: Water cannons on protestors in HOng Kong. Source: Photograph by Studio Incendo under Creative Commons LIcense

The current wave of protests in Hong Kong and the limited feminist engagement with them need to be set in the context of the city’s longer struggle for democracy and autonomy and the relative weakness of its local feminist organisations. Hong Kong was a British colony from 1842 until 1997, when it was handed back to China on the basis of a Sino-British joint declaration signed in 1984. This agreement was supposed to guarantee Hong Kong a large degree of autonomy under the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ model, which gave its citizens far more freedom than their counterparts in China. It was also expected that Hong Kong people would be able to elect their own leaders under a fully democratic system. Not only have these promises of democracy not been realised, but the Beijing government has progressively tightened its control over Hong Kong and intervened more and more in its internal governance, threatening the freedoms of its citizens. These freedoms have made it possible for feminists to organise and to make some progress on limited basic rights, but the feminist movement is neither strong nor particularly radical. LGBTQI+ organisations and activism also exist but have made even less progress given the government’s promotion of heterosexual family values. Feminists and LGBTQI+ activists have been active in the campaign for democracy, which has been ongoing for several years, but have rarely promoted their own agendas within these wider campaigns so that issues of gender and sexuality have largely been ignored and seen as irrelevant to the movement’s goals.

The Beijing government has progressively tightened its control over Hong Kong and intervened more and more in its internal governance, threatening the freedoms of its citizens.

The biggest pro-democracy event prior to the current protests was the Umbrella Movement of 2014, which involved a 79-day peaceful mass occupation of main roads in three central districts of Hong Kong. In the summer of 2019, the introduction of a bill allowing extradition from Hong Kong to mainland China sparked mass demonstrations in Hong Kong that quickly developed into a wider, pro-democracy anti-government movement resulting in months of protests. In the face of government intransigence and police brutality, the protests have become more confrontational and violent, and have been met with increased use of force by the police. How can and should feminists respond to this escalating cycle of violence? What interventions are feminists making within the movement? What concerns cannot be voiced? It is obviously very necessary to condemn the excessive use of force by the police and their sexual harassment of and assaults on women protesters. We also, however, need to go beyond this to think about the wider effects of the culture of violence on women and on marginalised individuals and communities and break through the silences imposed by the prevalence of the Valiant ideology in the movement. Young people, including young women, are risking their health, lives and futures in facing the forces the police unleash against them, and you have to admire their courage and feel outraged at the injuries they are suffering. In this context raising any doubts about movement tactics and their wider social effects is hard. Moreover, feminist issues can – and often are – seen as inconsequential in the context of fighting for the future of Hong Kong, as an unnecessary distraction from the main struggle against the authoritarianism of the Chinese regime. One consequence of this is that authoritarianism within the democracy movement goes unchallenged.

Moreover, feminist issues can – and often are – seen as inconsequential in the context of fighting for the future of Hong Kong, as an unnecessary distraction from the main struggle against the authoritarianism of the Chinese regime.

Authoritarianism of the pro-democracy camp

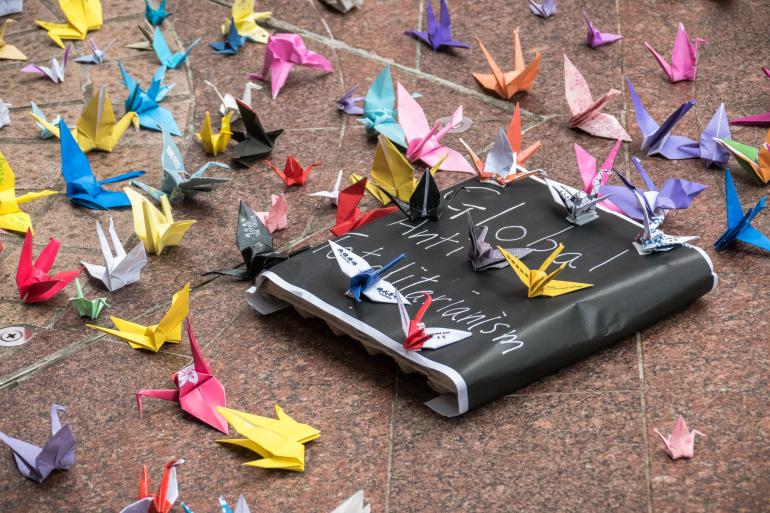

Online platforms and electronic communication have facilitated the spontaneous, dispersed, democratic forms of protest characterising the movement in Hong Kong. A variety of different forms of protest can thus be promoted and organised from the grassroots of a leaderless movement. Thus on any given weekend in Hong Kong, while those trashing symbols of ‘red capital’ (Chinese banks and companies) and ‘blue’ (pro-government) businesses and engaging in running battles with the police hit the headlines, other democracy activists will be peacefully making paper cranes or holding singing protests. This decentred online organising, however, also has a darker side in that the same platforms and means of communication can be used spread fake news, promote hatred and to harass others – not only opponents of the movement but also those who break with the ethos of unconditional support for the Valiant ideology. The movement does not have identifiable leaders but it does have a hegemonic ideology so that supporters of the movement who oppose violence are left without a legitimate voice. This has particular consequences on the kind of feminist interventions that can be made.

This decentred online organising, however, also has a darker side in that the same platforms and means of communication can be used spread fake news, promote hatred and to harass others – not only opponents of the movement but also those who break with the ethos of unconditional support for the Valiant ideology.

Feminists can and have spoken out against police brutality and sexual assaults on and harassment of women protesters. Some have appropriated traditional feminine roles, for example as mothers positioned as protecting the young, as housewives demonstrating that they are part of society and have a political voice. Young women on the front lines can also, of course, be seen as a valuable part of the struggle; they are among the Valiant, no longer materialistic ‘Kong girls’ but brave fighters.[1] In these respects women in general and feminism in particular can be seen as useful to the movement, as helping to advance the struggle.

There are, however, more uncomfortable issues on which feminists keep silent, particularly about violence and misogyny within the movement. Feminists should be able to develop a critical stance on this – not necessarily one of outright pacifism or opposition to any political violence – but it ought to be possible to raise questions about violence and its wider gendered effects as well as its consequences for disadvantaged minorities and society as a whole. Using sexist and sexual slurs against political opponents and to police women has become almost routine. Police women are called whores and receive threats of rape. Shouldn’t feminists have something to say about this? Is it acceptable, for example, for the justifiable anger towards the police to be extended to threats against the wives of policemen? (Note that the husbands of police women seem to escape this). Isn’t this to treat wives as mere appendages of or property of men? Is it feminist to accept or even endorse this? Is a slogan threatening death to the families of police, positioning them, again, as mere property, acceptable to feminists?

Image description: Back of woman with bow and arrow. Source: Source: Photograph by Studio Incendo under Creative Commons LIcense

Intersectionality in the movement (or Multiple inequalities within a democracy movement)

Intersectional analysis has become mainstream within feminism, which implies that axes of inequality other than gender should be of concern. So why, when visually impaired people complain that protesters’ destruction of traffic lights makes it impossible to cross the road safely and are then told that this is not a priority. Shouldn’t feminists support them? Racism is another issue. The ultimate enemy is the Beijing government, but this has been extended to racialized hostility towards individual mainlanders. This racialization was evident in Hong Kong before the movement, but has become much worse, leading mainland Chinese living in Hong Kong to fear for their safety. Inspiring such fear is somehow seen as advancing the movement. How can it be? Even if vandalising Chinese-owned business is important to send a message to Beijing, the way we treat individual Mainlanders and have private execution of provocateurs including stripping them and beating them up seems to be going too far. Do feminists pretend that they do not see?

What has become impermissible is voicing anything critical of any aspect of movement tactics. Those who do dare to speak out, become targets of sustained online harassment – and again of threats of violence couched in misogynist terms. Few dare to support them in public internet forums, further exacerbating the culture of silence.

In a leaderless movement with no big stage, it is almost exceptional that we do not have to be bothered by prominent male leaders doing all the talking and pointing us in the right direction as if they have superior knowledge of the bigger picture.

In a leaderless movement with no big stage, it is almost exceptional that we do not have to be bothered by prominent male leaders doing all the talking and pointing us in the right direction as if they have superior knowledge of the bigger picture. Young protesters and their multiple telegram groups and the LIHKG forum[2] have created a new ethos for the movement. This democratic participation seems to make us insensitive to the masculine norms behind it. With a new articulation on solidarity - the integration of Valiant and Pacifist, there may be more space for collaboration rather than struggles to compete for leadership. People with different political orientations are supposed to join hands rather than sever the mattress that we both sit on (meaning unfriending each other). What cannot be talked about is what this new solidarity really means. In fact, it means that there is only one thing we should all do and that is to protect the young protesters, the Valiant. The Pacifists can never sever the mattress. We have to defend the movement at all cost. Otherwise, we will lose the battle against authoritarian rule. How is this solidarity possible? It comes at a cost. We are not allowed to talk about issues that will divert attention away from the broader movement. As the Chinese saying goes, we should all endure all disgrace to bear a heavy burden even if it involves swallowing humiliation in order to carry out an important mission – to liberate Hong Kong, the revolution of our times. So where is feminism in this? Should we just sell our souls to the movement? Can’t we at least promote a feminist ethic of care and acknowledge the hurts inflicted within and beyond the democracy movement, not just to women but also other marginalised sectors of society?

What is the “revolution of our times”? what kind of revolution do we want?

Feminists in Hong Kong do have analyses of sexual violence, justice and equality, but there is little public understanding of this, of why it is unacceptable to use sexual threats against women who are political enemies or those within the movement who are deemed to be less than wholehearted supporters of the valiant camp. Feminists in other countries where feminist discourse has become more mainstream have been able to push back against such behaviour, but this is less possible in Hong Kong as even its more progressive citizens seem unable to see a problem. Thus any feminist who does speak out is open to attack from Hong Kong’s netizens. Feminist concerns more generally, are seen as either irrelevant or not pressing given the urgent need to fight for democracy and freedom. Yet if this is "a revolution of our times" (a key slogan of the protests) there should be a place for feminism within it – otherwise it is not a revolution, merely a shift in power from one sector of society to another. Any struggle for democracy and freedom should be concerned with wider issues of social justice and equality for all, where a feminist perspective is essential.

Yet if this is "a revolution of our times" (a key slogan of the protests) there should be a place for feminism within it – otherwise it is not a revolution, merely a shift in power from one sector of society to another.

Image description: Paper cranes on text saying Global anti-totalitarianism. Source: Source: Photograph by Studio Incendo under Creative Commons LIcense

Footnotes

[1] "Gong Nui" come from the phrase "Hong Kong’s girl". Many Hong Kong internet forum users use this word to describe the females they met in Hong Kong which are materialistic, snobbish, superficial, bad-tempered, self-centered and selfish. Sometime, "Gong Nui" is used to mention women who are "gold worshipper" (money-minded) and have "Princess Sickness” (they act as if they were princesses waiting for others to serve them)

[2] LIHKG Forum (連登) is a multi-category forum website based in Hong Kong. The website is well-known for being the ultimate platform for discussing the strategies for the leaderless anti-extradition protests in 2019. The website has gained popularity since the launch in 2016, and is often referred to as the Hong Kong version of Reddit.

- 16765 views

Add new comment