Image description: Text in Korean on notebook. Author's Facebook post in 2017. Source:Soo Ryon Yoon

Me Too movement in South Korea has exploded since 2018 with prosecutor Seo Ji Hyun’s interview on major news network JTBC. She testified against her superior and senior prosecutor, Ahn Tae-geun, who had sexually assaulted her in public.[1] Her interview was powerful not only because of her intrepidity to expose her own perpetrator; it was her uncovering of how the Supreme Prosecutors’ Office of the Republic of Korea, the towering presence that has a significant impact on the South Korean legal and judicial system, was trying to cover up the assault case and then retaliate against Seo by demoting her.[2]

Seo’s interview resonated powerfully, especially with those of who had been under the impression that women in the upper echelon of the society, especially a prosecutor, would be relatively more safe from sexual violence in the workplace. As was somewhat expected, a series of other high profile sexual harassment and assault cases both in and beyond the political offices and government bodies would soon follow, similar to the way in which #MeToo had started a chain of reactions in the US where the hashtag movement first became mainstream. Seo’s interview, however, prompted a series of posts shared on Facebook and other online platforms against sexual assault perpetrators by an unexpected group of people amidst the explosion of high-profile Me Too cases: theatre actors.

As was somewhat expected, a series of other high profile sexual harassment and assault cases both in and beyond the political offices and government bodies would soon follow, similar to the way in which #MeToo had started a chain of reactions in the US where the hashtag movement first became mainstream.

The fact that theatre actors’ Facebook posts were met with a complete surprise and that they sent a shock wave throughout the entire nation is partly shaped by the general public’s skewed perception: somehow, theatre as an artistic genre and a form of community is considered to be detached from the real world, and that theatre world has just recently come to reckon with its own history of sexual violence only after the initial #MeToo circulation. This stereotype, or what one might call antitheatrical prejudice, tends to treat theatre as exceptional space and overlooks the fact that theatre actors have had to deal with sexual violence, but only internally due to the potentially fatal risks associated with speaking out. This prejudice has had an impact on performing arts not just in South Korea but globally. As a result, theatre actors’ efforts to bring justice to the field of performing arts received widespread media coverage.

However, how online and digital cultural practices have enriched, if not enabled, the movement deserves more attention. Describing what could only be considered as decades-long serial rape and sexual harassment cases, several actors chimed in on Seo Ji-hyun’s interview by publicly posting on Facebook and one of the biggest South Korean online forums DC Inside about their own experiences with artistic directors and producers Lee Youn-taek, Yoon Ho-jin, Oh Taeseok and Ha Yong-bu, to name a few. These internationally acclaimed artists, whose works focus on nationalized decolonial theatre-making by adapting and rewriting well known dramatic canons of Shakespeare and other European playwrights, have been much studied and praised in South Korea and abroad in the field of performing arts and regarded as champions of theatre innovation.[3] The actors’ posts struck many readers as shocking, not simply for the fact of sexual assault perpetrated by respectable artists, but more because the entire performing arts industry had been able to normalise rape culture for as long as several decades.

What has partly shaped this normalisation is that performing arts troupes in South Korea often function like a tightly-knit clan or a closed network of fictive kinship (many of the accused artists were leaders of theatre collectives and communes, where they would live, train and rehearse with actors for months in preparation for large scale productions and international tours), where leading male directors are regarded as “masters” and father figures to young actors and directors in training. This hierarchical relationship relies on a constant performance of intimacy and emotional labour, often sustained by what is infamously known as gapjil, bullying and intimidation by someone who abuses their power and privilege, and wiryeok, a form of power that one may wield using their position especially in a workplace. Unwanted physical contact, verbal abuse and sexualisation of actors have been tolerated and inherited from a generation of theatre-makers to another all under the guise of teaching theatre methods, practising pedagogic relationality, and building a stronger community.[4]

This hierarchical relationship relies on a constant performance of intimacy and emotional labour, often sustained by what is infamously known as gapjil, bullying and intimidation by someone who abuses their power and privilege, and wiryeok, a form of power that one may wield using their position especially in a workplace.

Theatre actors are also bound by the legal hurdles and risks specific to the South Korean context, which often act as a silencing mechanism for victims, activists and whistleblowers. Some point out that the cartel-like culture amongst powerful perpetrators, like that of the theatre community, feeds on the gaps in the existing legal and institutional structure. For instance, sexual offenders have used a defamation and libel suit to retaliate against victims, who may then feel the pressure to retract their statement or drop an ongoing lawsuit. The withdrawal potentially affects the accusing victims adversely, for the offender can then file a criminal complaint against them for having made a false statement in the first place. Thus, anti-sexual violence activists and legal experts criticize the relative convenience and expediency in bringing a defamation suit against accusing victims. For example, an offender may simply submit a screenshot of texts on a social media platform posted by an accusing victim as a piece of evidence of defamation. In such a case, victims will be summoned by the police to “disprove” the offender’s claim. Compared to this, accusing victims must often endure a long, arduous and often traumatizing process, at various levels of which they must rehearse their statement of experiences and details of sexual assault over and over again until they are proven truthful enough.

#MeToo movement in South Korea has thus brought the public’s attention to the vague expressions in the existing Article 307 of the Criminal Law, and many have called for a revision of the article to protect sexual assault victims against further victimization and legal liability. The existing clauses may as well be abused to mean that simply making public statements about the “facts” of sexual assault will constitute a criminal offence. Indeed, defamation suits were swiftly filed against activists and victims in high-profile #MeToo cases involving Kim Ki-duk, internationally acclaimed and award-winning film director, and Ko Un, poet and Nobel Prize front runner. The court found that their defamation complaints had no grounds, and both Kim and Ko lost their cases. However, cases like these have a long-lasting impact, which continues to haunt not just the victims but also the involved activists, journalists and lawyers. Anti-sexual violence activist groups and victims in the arts now demand that the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism implement measures to protect and support sexual assault victims threatened with legal actions.

While the theatre Me Too movement gained traction thanks to the wave of support through successful albeit difficult legal battles and anti-sexual violence public discourse, there has been little to no serious attention paid to how digital culture and its practices actually affected and enabled the movement beyond the more general impact of the #MeToo circulation, with regard to the theatre Me Too movement and the broader anti-sexual violence movement online. To be sure, hashtag activism like the #MeToo movement is not without its own limits, especially considering its potentially colonising effect. At times, it seems to undermine and flatten out complex and nuanced discussions within an ongoing political discourse unique to a local context, and capitalises on what Khoja-Moolji calls the “affective intensities” that often rely on outdated and hegemonic understandings of survivors and various agents involved (such as the young women in the Nigerian Boko Haram kidnapping case, the concerns around which were shared through #BringBackOurGirls).[5]

To be sure, hashtag activism like the #MeToo movement is not without its own limits, especially considering its potentially colonising effect.

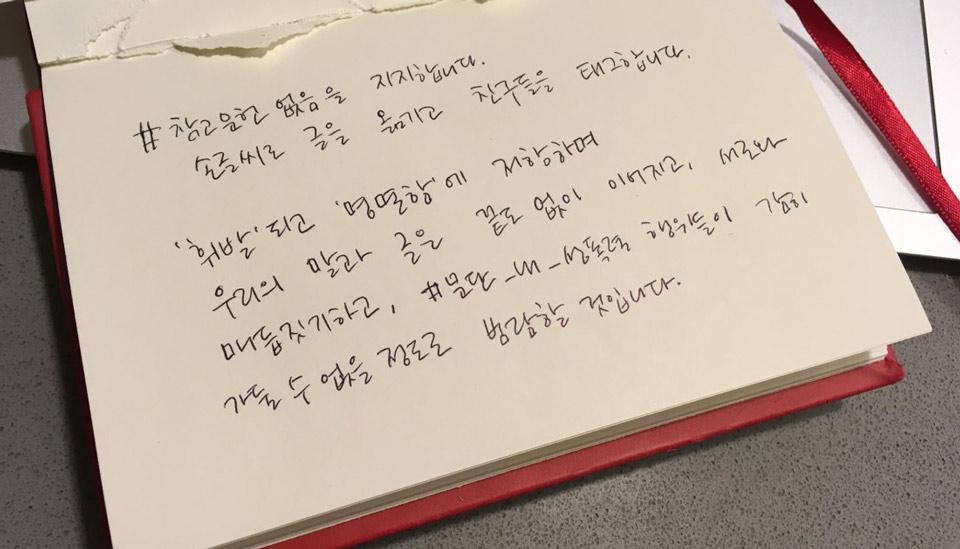

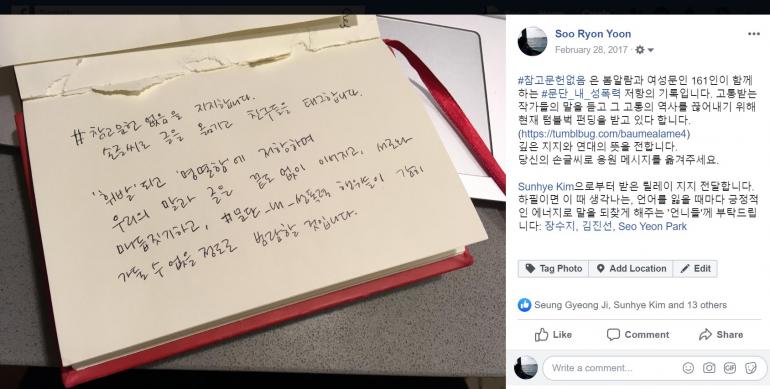

Nevertheless, it is equally important to recognise that, in the South Korean context, #MeToo also builds upon and is in dialogue with ongoing uses of hashtags such as #연극계_내_성폭력 (“#sexualviolenceintheatre”) or #예술계_내_성폭력 (“sexualviolenceinthearts”), which had been circulating since 2016, predating Seo Ji Hyun’s interview and the actors’ public posts.[6] This calls for more engaged and digital culture-specific discussions around how #MeToo, in return, has had an impact on the existing online spaces where other forms of hashtagging were already calling out perpetrators and various fields of the arts and culture in 2016.[7] Some of these hashtags include #__내 성폭력 (“#sexualviolencein___”), which Facebook and Twitter users filled with “literature,” “filmmaking,” “dance” and so on.[8] Facebook users like myself participated in a “relay tagging,” or what is more widely known as a hashtag challenge, to call attention to sexual violence in South Korean literature and publishing industry by using #참고문헌없음 (“#withnoreferences”) and #문단_내_성폭력(“sexualviolenceinliteraryworld”) in 2017. The hashtag was in reference to the women writers’ refusal to be part of the tradition and legacy of the literary world dominated by male writers and their normalisation of sexual violence within literary circles. The campaign was initiated by women writers, who contributed to an anthology, <참고문헌 없음> (With No Reference) as a result of this hashtag movement.[Fig1] The anthology was funded through a crowdfunding campaign, which collected over sixty million Korean won (the equivalent of sixty thousand U.S. dollars) from over two thousand donors.

Figure 1. My Facebook post in 2017, where I tagged friends to join the #withnoreferences campaign

Taking this context into consideration, what I suggest here is that the long-term, sustained online cultural practices by the theatre fandom have given much-needed support and momentum for the theatre actors in the 2018 Me Too movement. At the same time, the theatre Me Too movement has, in turn, prompted the fandom to renew their interests in and sense of belonging to the field of performing arts. These have evolved into a series of collective actions that demand more accountability and self-reflexivity from both theatre-makers and audiences.[9] This dialogue between various old, new, and extant online communities of people also signals a new way of producing, sharing, disseminating and archiving knowledge of sexual violence in performing arts, in which “insider knowledge” and the interior workings of the artistic prerogative of the select few “masters” have always remained somewhat opaque to a general audience. For example, the theatre Me Too movement was unique in that the fandom mobilised theatregoers primarily on online platforms and fan forums to boycott productions staged by the accused directors. They then expanded this and took to streets to stage sit-ins, rallies and audience-led post-show gatherings, during which they used a hashtag, #With_You, as a response to #MeToo.

Theatre and Musical Gallery (연극뮤지컬갤러리), a public subgroup within the popular online forum DC Inside, played an especially crucial role in helping both actors and fans’ interests and concerns coalesce. DC Inside, which originally opened in 1999 as an online forum where users exchanged information about digital cameras (hence the name, “DC”), has produced a wide array of subcultures and grown to host around two thousand open boards, or “galleries,” where users discuss topics ranging from cars to K-pop idols to current political affairs. Despite the rampant culture of misogyny and radical right-wing politics within DC Inside, Theatre and Musical Gallery remains to be a rich deposit of news clippings, video documentations, diverse user remarks and survivors’ accounts of sexual assault cases posted and compiled by the frequent posters. The site was a place where, in addition to Facebook and Twitter, a number of actors and university students majoring in acting came forward to call out their teachers, directors, playwrights, choreographers and senior members of performing arts troupes. Theatre and Musical Gallery and the theatre Me Too movement erupted into what could be considered a unique way of sharing narratives of and assembling fragmented information about gender and sexual politics in performing arts.

Theatre and Musical Gallery and the theatre Me Too movement erupted into what could be considered a unique way of sharing narratives of and assembling fragmented information about gender and sexual politics in performing arts.

These instances partly illustrate how both online cultures and “offline” mobilization continue to synergize one another. Rather than understanding online data to be simply feeding the “offline” movement or merely mirroring what happens physically “on site,” online communities and digital cultural practices associated with the theatre Me Too movement show us how a new network of previously disparate individuals can emerge, connecting feminist activists, legal experts, theatre actors and theatre audiences together. This also calls for an initiative to theorize how the linkage between online cultural practices, discursive circulation, theatre stage and pre-existing activism is sustained or challenged in an unexpected direction compared to the non-North American and non-European context, where consent, theatre-making and terms of labour conditions may be defined and applied very differently.[10] A case in point is also demonstrated by one of the theatre Me Too survivors, Park Younghee, who wrote that the theatre Me Too movement, which had started with a series of separate, individual survivor stories online, quickly grew to help form a group of twenty-three plaintiffs and a coalition of legal and academic experts who brought down Lee Yountaek in a legal battle.[11]

These initial cases of online mobilization and hashtag circulation have also resulted in Theater with You, an online coalition of theatre actors against sexual violence on Facebook, which organizes online petitions, seminars, workshops, press conferences and group visits to trial hearings to name a few of its various activities. One of its achievements is its online distribution of a handbook about how to challenge and survive an exploitative situation on stage, in rehearsals, in practice spaces and on backstage as actors or junior staff members. Modelled after the Chicago Theatre Standards (CTS) and the hashtag campaign, #NotInOurHouse, the handbook becomes a toolkit for actors and creative staff to imagine and map a creative space that protects and allows for a more ethical and democratic relationship among the theatre community as a whole. Despite how some of the mainstream think pieces characterize the Me Too movement as having only just arrived in South Korea, the sustained engagement of the actors, activists and theatre fandom with a series of culture-specific online practices, online community spaces and offline mobilizing urges us to reconsider the ways that the Me Too movement maps a different geography in the South Korean context.

Despite how some of the mainstream think pieces characterize the Me Too movement as having only just arrived in South Korea, the sustained engagement of the actors, activists and theatre fandom with a series of culture-specific online practices, online community spaces and offline mobilizing urges us to reconsider the ways that the Me Too movement maps a different geography in the South Korean context.

[1] I refer to both the hashtag (#MeToo) as a circulating reference point, and the label “Me Too movement” to specifically recognise the local context, in which protests as well as legal and political acts have been part of mitu undong (미투운동 The Me Too movement) in South Korea.

[2] This piece follows the Korean naming convention, in which the last name comes first, followed by the first name.

[3] See, for example, Global Shakespeares: Video and performance archive. https://globalshakespeares.mit.edu/director/oh-tae-suk/; Lee, H. (2015). Performing the Nation in Global Korea: Transnational Theatre. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; Modern Korean theatre. In K. J. Wetmore, Jr., S. Liu, & E. B. Mee (Eds.), Modern Asian Theatre and Performance 1900-2000. London; New York: Bloomsbury.

[4] Lee Youn-taek, the internationally renowned theatre artist and sexual assault perpetrator who led theatre company Yeonheedan georipae (Yeonhee Street Theatre Troupe) and theatre commune Milyang Theatre Village, reportedly said that he was being punished for doing what the theatre world had always considered its tradition, and that the general public did not seem to understand the prerogative of theatre artists.

[5] Khoja-Moolji, S. (2015). Becoming an ‘intimate publics’: Exploring the affective intensities of hashtag feminism. Feminist Media Studies, 15(2), 347-50. See also https://www.hashtagfeminism.com/research.

[6] See also, Kim, M. (2017, 28 April). 가해자가 기록한 #예술계_내_성폭력 (#Sexualviolenceinthearts documented by a perpetrator). 문화플러스서울 (Culture plus Seoul). https://brunch.co.kr/@sfac/233

[7] The phrase itself had been introduced by Tarana Burke in 2006 on MySpace before it spread globally in a hashtag form primarily prompted by the women who spoke out against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein in 2017. See Abby Ohlheiser, “The woman behind ‘Me Too’ knew the power of the phrase when she created it - 10 years ago.” The Washington Post 19 October 2017.

[8] Kim, B., & Kim, B (Eds.) (2019). 그것은 연기가 아니라 성폭력입니다 (It is not acting; it is sexual violence). 스스로 해일이 된 여자들 (Women who have become tidal waves). 서울(Seoul): 서해문집(Seohaemunjip). 128-51.

[9] Recent studies on the uses of hashtags in online feminist activism and progressive social activism commonly point out how the personal/private narratives of survivors of sexual assault and workplace harassment have taken to online where their voices are amplified, and where they can share the sense of solidarity with a mass group of sympathetic yet anonymous users. See 김효인 Kim, H. (2017). SNS 해시태그를 통해 본 여성들의 저항 실천 - ‘#00_내_성폭력’ 분석을 중심으로 (Women’s resistance action seen through SNS hashtags -- Focusing on ‘sexual violence in 00’”). 미디어, 젠더 & 문화 (Media, Gender, and Culture), 32(4), 5-70; 김희정 Kim, H. (2016). 우리는 모두 ‘사건’에 응답해야 한다 -- ‘00 내 성폭력’ 해시태그 운동에 부쳐 (We all have to respond to the ‘incident’ -- on ‘sexual violence in 00’ hashtag campaign). 진보평론 (The Radical Review), 70, 278-88; 조서연 Cho, S. (2016). 남성 연대의 구성과 균열 - 성폭력 폭로 해시태그와 박근혜, 최순실 게이트에 부쳐 (Construction and fissures in male solidarity – on anti-sexual violence hashtags and the Park Geun-hye-Choi Soon-sil scandal). 문학과 사회 (Literature and Society), 29(4), 35-49.

[10] See the forthcoming issue of Performance Paradigm, in which co-editors Caroline Wake and Emma Willis critique how research on feminism of the Southern Hemisphere in theatre and performance studies has provided “raw data” to the studies in “metropole,” notwithstanding the continued regional differences as well as consistent efforts to theorize feminist theatre and performance. https://www.performanceparadigm.net/index.php/journal/announcement.

[11] 박영희 Park, Younghee. (2018, 8 October). 기울어진 극장 미투 이후, 건강한 예술계를 위해 싸우는 여성들 (Unlevel stage After the Me Too movement, women fight for a healthier world of the arts). 여성신문 (Women News). http://www.womennews.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=144899.

- 6586 views

Add new comment