This is an attempt to narrate the speak-out movement led by the Dalit-Bahujan women in Kerala. It is a social media-based (particularly through Facebook) campaign, that is still ongoing in Kerala, to narrativise the experiences of sexual harassment faced by Dalit-Bahujan women. These attacks had happened in their work place, within friends’ circles and political spaces. Surprisingly, the women faced attack and criticism from their Malayali upper caste and Dalit male friends, who are known for their political activism and progressiveness. These women used social media as a platform to reveal their experience in order to get support and solidarity from the public. Kerala has never before witnessed such a movement initiated by Dalit-Subaltern women before, and it continues to be widely discussed and debated in social media.

These attacks had happened in their work place, within friends’ circles and political spaces.

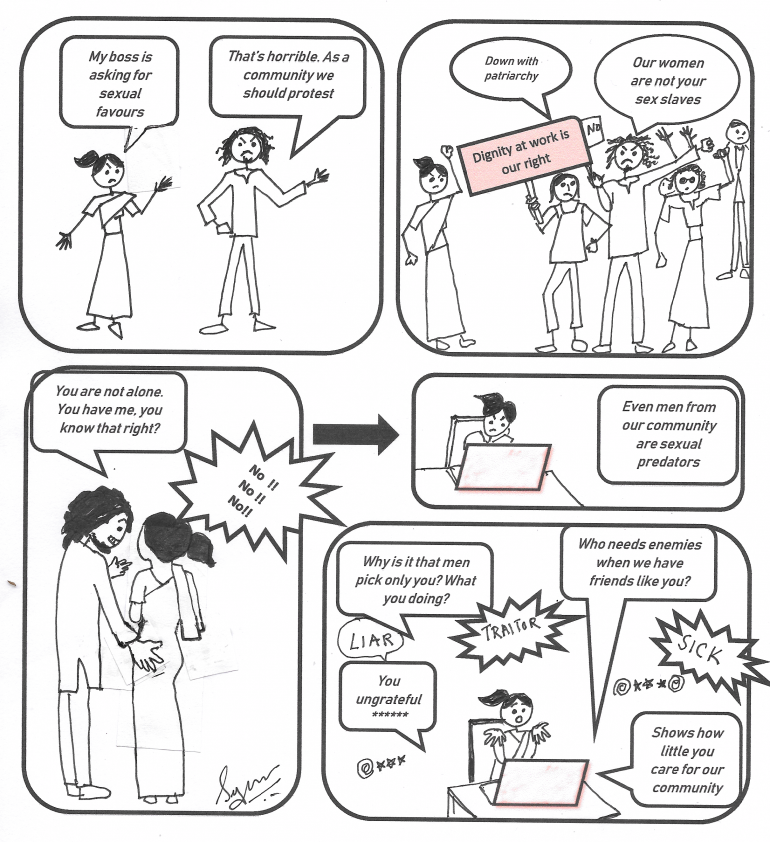

Initially, a Bahujan woman student from the University of Hyderabad posted on Facebook about the slut shaming and rape threats she was subjected to by her friend. Many Dalit women extended their solidarity to her and eventually some other Dalit women also came forward and spoke about similar experiences. A Dalit woman journalist wrote in detail about the sexual harassment she had faced from the Dalit documentary activist Rupesh Kumar, when she was travelling with him to report on the Thoothukudi, Tamilnadu police firing incident. Her Facebook posts were widely shared and sparked off a massive discussion in online spaces. Following this, another woman came out with a statement saying that she was molested by a savarna activist Rejesh Paul when she was a minor. Prominent Dalit feminist and writer Rekha Raj also openly expressed her solidarity and offered legal support to these women. She wrote a detailed note on Facebook regarding the various sexual assaults done by Rejesh Paul and Rupesh Kumar to many Dalit and Bahujan women. Following this, many other women including trans people from all social locations came out with Facebook posts on their experience.

Dalit-Bahujan women and Social Media

Dalit-Bahujan women, particularly Dalit women, do not consider social media as a space merely for entertainment. Instead they use it as a platform to articulate their lived experiences and place important political questions. To access physical public spaces and to be audible in them is a challenging task for marginalised women, since the public, whose consciousness is casteist, sexist and gendered, always tries to mute them. Nowadays, a tiny group of educated Dalit–Bahujan women who have access to the internet respond often and swiftly to political issues. This certainly guarantees public attention. Also social media offers the possibility of articulation of unheard voices without outside mediation. The self-reflexive engagements of Dalit women are getting wider visibility in the cyber space, which was only available till now to privileged women with access. Dalit women also become opinion-makers in online spaces as representatives of their own life struggles - transforming their lived experiences into political articulations. As a result of their relentless efforts and intervention in social media, the mainstream media has also been forced to seek out the opinions of Dalit women.

Dalit-Bahujan women use social media as a platform to articulate their lived experiences and place important political questions.

A majority of the Facebook posts by Dalit-Bahujan women are either in the form of social criticism or express their dissatisfaction with the dominant discourse(s). Dominant caste women have the privilege to express their opinions using sarcasm. Thus Dalit women are portrayed as fighters and hate-mongers, and overly emotional by the larger public even on Facebook. In addition to that, a few Dalit-Bahujan people have branded the engagements of these women in online spaces as “elite”, and have then further demanded that they should work at the ground level, even though these women have the experience of ground level activism and their own life experiences. Therefore the ongoing speak-out campaign in Kerala is very relevant since it breaks the conventional imagery of Dalit-Bahujan women.

Dalit women are portrayed as fighters and hate-mongers, and overly emotional.

No More Victims: The Politics of ReveAling

This campaign has totally rejected victimhood when the survivor revealed their identity through social media. A 24 year old Dalit woman journalist gave a detailed account on Facebook of the sexual harassment she had faced and said she wants to be known as a survivor of it. Some Dalit- Bahujan women from Kerala took a sharp stand against sexual assault by rejecting victimhood. Dalit feminist Rekha Raj observes “it is not a campaign for claiming the victim status but an assertive movement by survivors of sexual assault who politically articulate their experience and expose the abusive men in the progressive public spaces”.

A 24 year old Dalit woman journalist gave a detailed account on Facebook of the sexual harassment she had faced and said she wants to be known as a survivor of it.

Another woman from dominant caste background says that Jeevan Thomas, a painter-cum-culptor, tried to sexually abuse her after their “intellectual” discussions on painting that he then made about “liberating women’s bodies. A Dalit Christian woman student also shared a similar experience of moral policing from Rejesh Paul, when she resisted his violence. These “progressive men” used to mock their young women friends as “moralistic” for not cooperating with their sexual fantasies. All the women in the speak-out campaign have experienced this bogus politics from these “liberal", "intellectual", "activist” men.

The women who are involved in public platforms for women’s rights, Dalits and anti-fascist human rights activism need to work, travel and stay with their male colleagues. The engagements of these women in the public were regarded as consent for sex or sexual availability, because they have crossed the socially permissible limits (of spaces they can go to, timings etc.) for women. The accused men use the well known progressive circles that they are part of to abuse young women who are drawn to and want to engage in these social activities.

The accused men use the well known progressive circles that they are part of to abuse young women who are drawn to and want to engage in these social activities.

These men are considered to be different from ordinary males because of their “intellectual” positions and their subculture of followers, and so on. They however understand women’s friendship or companionship as consent for sex and this has been the experience of all women in the speak-out campaign. These instances provide a clear image of the double-stand of these abusive men who have also used social media often for their own activism. Consequently the speak-out movement brilliantly resisted and exposed them in public through the Facebook campaign.

Comic by Sylvia Karpagam (full)

Social Media and the Speak-Out Campaign

Though social media has played an important role in giving visibility, this does not mean that it is always supportive of Dalit-Bahujan women’s causes; rather this is contextual and issue oriented. The campaign began as one involving revelations on Facebook about sexual harassment incidents that happened in progressive circles and activist spaces. Dalit-Bahujan women came out to speak using various methods such as detailed Facebook statuses, live video and so on, and they shared detailed narrations and evidences about the instances of molestation along with the identity of the predators. Mainstream media further covered this movement and this received a lot of attention amongst the politically sensitive public. This moment of revelation on social media was termed as a second #metoo campaign; however it was different from that. The Indian academic #metoo campaign revealed the names of predators and subsequently the details of the incident in the public, while not revealing the identity of the survivors.

Dalit–Bahujan women came out to speak using various methods such as detailed Facebook statuses, live video and so on, and they shared detailed narrations and evidences about the instances of molestation along with the identity of the predators.

One of the important aspects of this campaign is that these women assert themselves as survivors because victimization is a normalised thing under due process. Generally, in India women suffering from sexual harassment face long-term trauma since justice is normally delayed, or never provided in the case of Dalit-Bahujan women. These women expressed that the brief and momentary support they received from social media was quite relevant, and also functioned as a relief to overcome the stressful time that followed the act of revelation. It can be read as a form of social justice provided by a sensitive public through Facebook, though it is relative.

The brief and momentary support they received from social media was quite relevant, and also functioned as a relief to overcome the stressful time that followed the act of revelation.

Kerala has recently witnessed two prominent sexual harassment cases, one is of the rape of a nun by a Catholic Bishop and another is that of the sexual assault of a woman activist by a member of legislative assembly from the Communist Party of India (Marxist). In both of these cases, the Catholic Church and the Marxist party used their mechanisms of power to suppress the women and tried to settle it within the system. In fact, these institutions, that function in many ways as parallel to the state, mute the voices of women and deny them public access to talk about these issues. Compared to this the Dalit-Bahujan women in this campaign have reached the public through social media without mediation and advocacy, which shows the courage to unmask the progressive masculine spaces of Kerala.

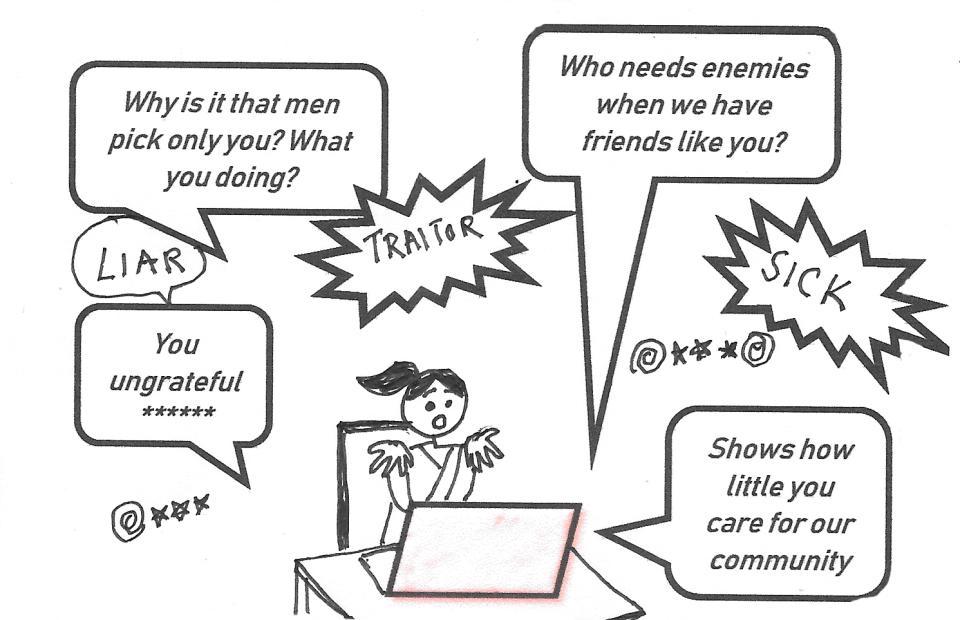

Unfortunately the harassers also get support through social media by alleging that the campaign itself is a lynch mob. The supporters of the accused say that they must be produced before law, but their social location and identity must be considered. Thus, social media also protects the culprits by defaming the women who came forward.

Social media also protects the culprits by defaming the women who came forward.

The campaign to protect the sexual preadators has emerged because the Brahminical value system of India has always seen Dalit-Bahujan women as morally suspect. Practices like the Devadasi system and sexual slavery are still prevalent in many parts of India to assure impunity for upper caste men and their access to the Dalit woman’s body. The Brahminical value system legitimises rape as part of the Hindu patriarchy, and consequently rape and any other sexual assault on Dalit-Bahujan women have been normalized in India. Groups with varying vested interests to maintain status quo in relation to caste and gender would counter this movement by Dalit-Bahujan women against Hindu patriarchal culture. Normally individual struggles of Dalit women hardly get any public support and media coverage. However, surprisingly this movement was widely accepted by the social media and the public. Moreover, this speak-out campaign influenced women from the dominant castes and they also started to reveal their experiences.

What this campaign sought to do was to visibilise sexual assault that is usually erased within movements that stand for “larger” political causes. Dalit-Bahujan women are claiming individuality by making their complete identity known and coming together in a collective struggle, refusing to be marked as Victim or as a nameless mass.

Dalit-Bahujan women are refusing to be marked as Victim or a nameless mass.

Footnotes

Surya, J. (4 August 2018). Poda Vedi: Women give it back. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kochi/poda-vedi-women-give-it-…

This article is based on the Facebook posts of women who revealed their experience of sexual assault.

I thank Rekha Raj, Gee Semmalar, Ria De and Joby Mathew for discussion and comments.

- 6618 views

Add new comment