Conversations around the platform economy are usually centred around ride-hailing and food delivery. Building on prior work on domestic work, we focused our attention on Urban Company (UC): The largest online platform for domestic work in India with over 32000 workers registered with the platform, and an estimated valuation of over $2BN.

UC Worker sign-up page: “Be your own boss. Work according to your time”. Source: Report

To workers, UC promises more clients and a substantial raise in their income while being able to control their time. Our research shows otherwise. During the course of our research titled, Designing Domestic Work Platforms: A Case Study of Urban Company, we talked to Ananya, who worked as a chef for urban homes in a large metropolitan area. Like other workers, she had lost most of her income in the last 2 years due to COVID-19. When UC started the ‘Home Chef’ segment in early 2022, she was excited to get back to work.

Initially, when Ananya joined Urban Company, she was hopeful that the unpaid ‘professional’ training she was required to attend and the uniforms she had to buy would lead to consistent work. Over time, however, her optimism turned into exhaustion as clients became rude, salary payment was delayed, and the company started forcing her to work longer hours, leaving little to no time for her family.

This experience isn’t unique: prior studies and the recent waves of protests have shown workers that the promises of comfortable and consistent platform work seldom materialise. Instead, they mostly lead to lower wages, overwork and poor working conditions for workers.

While the customer end of platforms is regularly discussed through the lens of human-centred design, the literature available on the design of the workers’ end is limited. The study of worker interaction with platform design is important for worker rights as previous work has shown the extent of psychological tricks, and algorithmic control that platforms attempt to impose on their workers.

In our research, we studied the platform design of UC to understand the experiences of workers in dealing with the platform, organisational values and the platform’s goals.

Standardisation and its costs

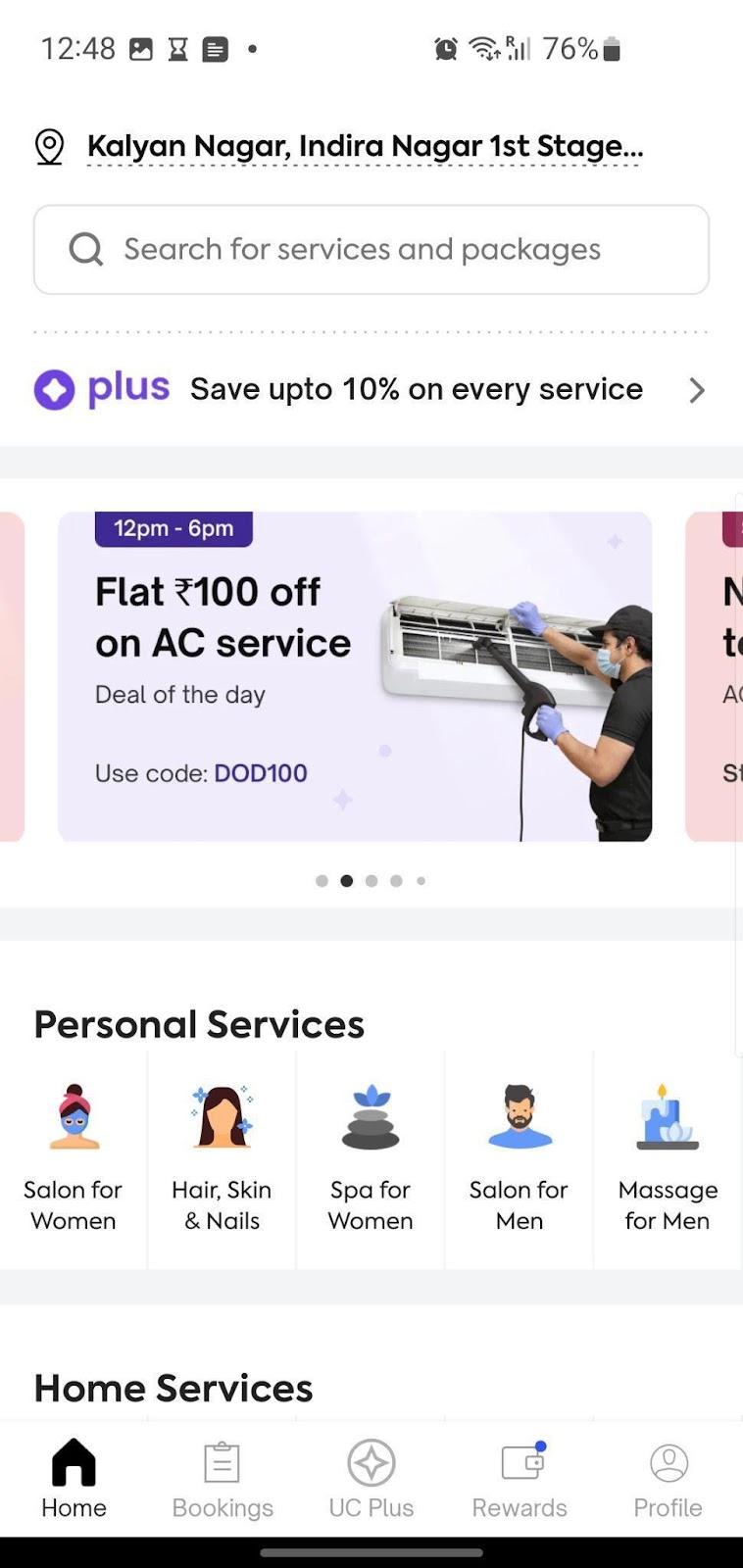

UC attempts to standardise domestic work in an effort to deliver uniformity to its customers. While standardisation allows the work to be measurable and reproducible, it is unsuccessful in capturing the personalised nature of services provided by workers. The UC interface lists tasks in each category like a salon, spa etc, with details of what to expect, how much it will cost and how long the service will take. However, each service is naturally different since each client has personalised needs. Artificially setting process and time expectations without consulting with workers sets them up for overwork. Further, the cost of carrying out this standardisation has to be fully borne by the worker in form of unpaid training, uniforms and materials, and not by the platform.

UC customer ends home page and haircut services page. Source: Report

To deliver a standardised customer experience, we found UC makes workers go through a mandatory yet unpaid training program before sending them any leads. The rigid and unpaid nature of the training impacts gender and caste-oppressed workers most, adding undue pressures on top of domestic care responsibilities.

“The training was supposed to start at 9 am and go till 6.30 pm. I didn’t know how I would manage my house or my work. I took leave for 15 days from two houses that I used to work at [to be able to attend the training].” -Ananya, home chef.

Standardisation further leads to an unrealistic expectation of temporal uniformity from workers. They get fixed time durations to travel, complete the task, and are asked to fill a minimum number of slots every day. All of this without accounting for the transit traffic, the complexity of tasks and the personalised nature of services. This temporal rigidity adds to lost wages, unmet customer expectations and penalties on workers for not meeting unreasonable targets set by the platform.

“Company tells you have 45 minutes and that’s it. We asked during [the] training how it’s possible [to cook] in 45 minutes. If they have taken [a] subscription for breakfast and lunch for five members, then how is it possible to do it in 45 minutes for five people? It’s not possible.“ - Ananya, home chef.

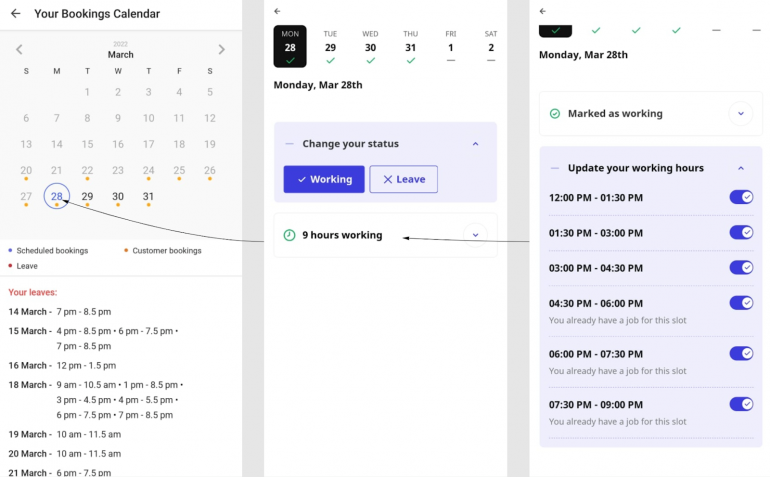

Here each slot is 90 minutes out of which 45 is assigned for travel, and 45 for the task. Source: Report

Metrics & Gamification

We found that worker targets and expectations are set through aggressive gamification. Converting tasks into metrics allows for these metrics to be optimised forcing workers to perform labour unrelated to the job they were hired to do.

The rating system is one example of a single number with far-reaching consequences for workers. UC uses a 5-star rating system to manage workers and curate customer feedback. Rating systems have been argued to be unrepresentative of service, heavily skewed to the extremes, and subject to the mood of customers.

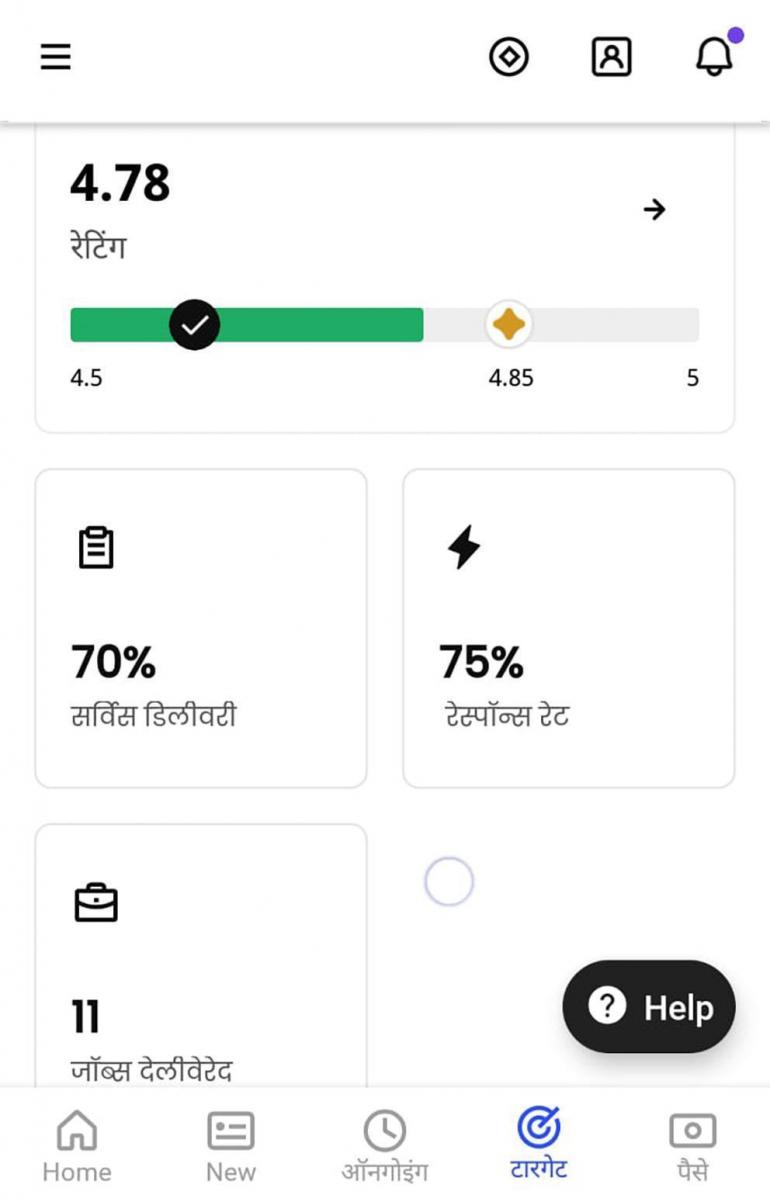

Rating screen showing service, response and delivery rates a worker must maintain to qualify for a guaranteed minimum pay program. Source: Report

The system is asymmetric and confers all power to the customer. During our research, workers told us that a few poor ratings in a row can lead to the deactivation of their profile (a rating below 4.7 is considered poor). This dynamic forces the workers to put in additional emotional and physical labour in hopes of getting better ratings from customers.

“If you take some work to a technician at their shop, the work gets done respectfully. But when you have to go to someone, there’s no respect given to you. They think that their servant has come. I’ll be honest, if, say there’s some dirt on the floor while we work, we have to clean that up as well. The customer makes us do everything. [...] if some water falls down, they’ll make us mop the floors as well.“ - Roshan, AC technician

Our research also found that the platform provides no meaningful way for workers to rate and filter out misbehaving customers. They are subject to the whims of customers who book a service on the app, unable to even control their sites of work.

Further, UC temporarily disables worker accounts for rejecting potential jobs that the algorithm surfaces to them. Workers are penalised for declining work despite the promise of letting workers choose their own clients and working hours.

“It’s like if you refuse three leads then they won’t assign you any job for one full day. So if it's 4-6 then probably they won’t assign you a job for one week. [...] Like I am saying that I don’t do pedicures. So if you don’t take up the lead of pedicure then they won’t assign you a facial job for one week.” - Maya, beauty worker.

Safety, Surveillance & Trust

Beyond the rosy marketing image of happy workers and customers, workers’ experiences suggest that hostility is embedded in the platform by design. UC focuses immensely on presenting the service as “safe and secure” for the customers while leaving the workers to shoulder the responsibility of this safety and security.

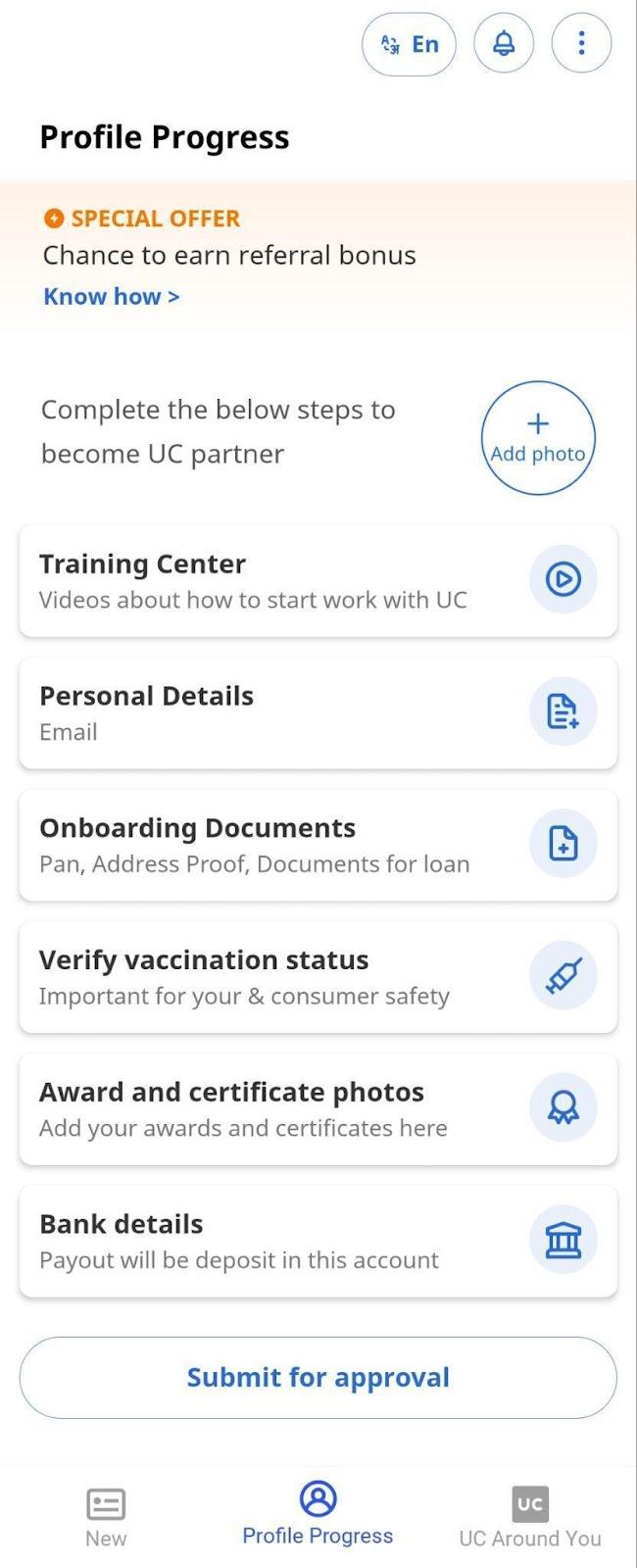

During the onboarding process, the workers have to submit multiple documents, do identity verification, attend customer interaction training, job training, etc., to ensure that promises made to the customer by the platform are kept. No verification or training is necessary as part of customer onboarding: the customer is considered trustworthy by default.

Extensive documentation is needed on worker signup. Source: Report

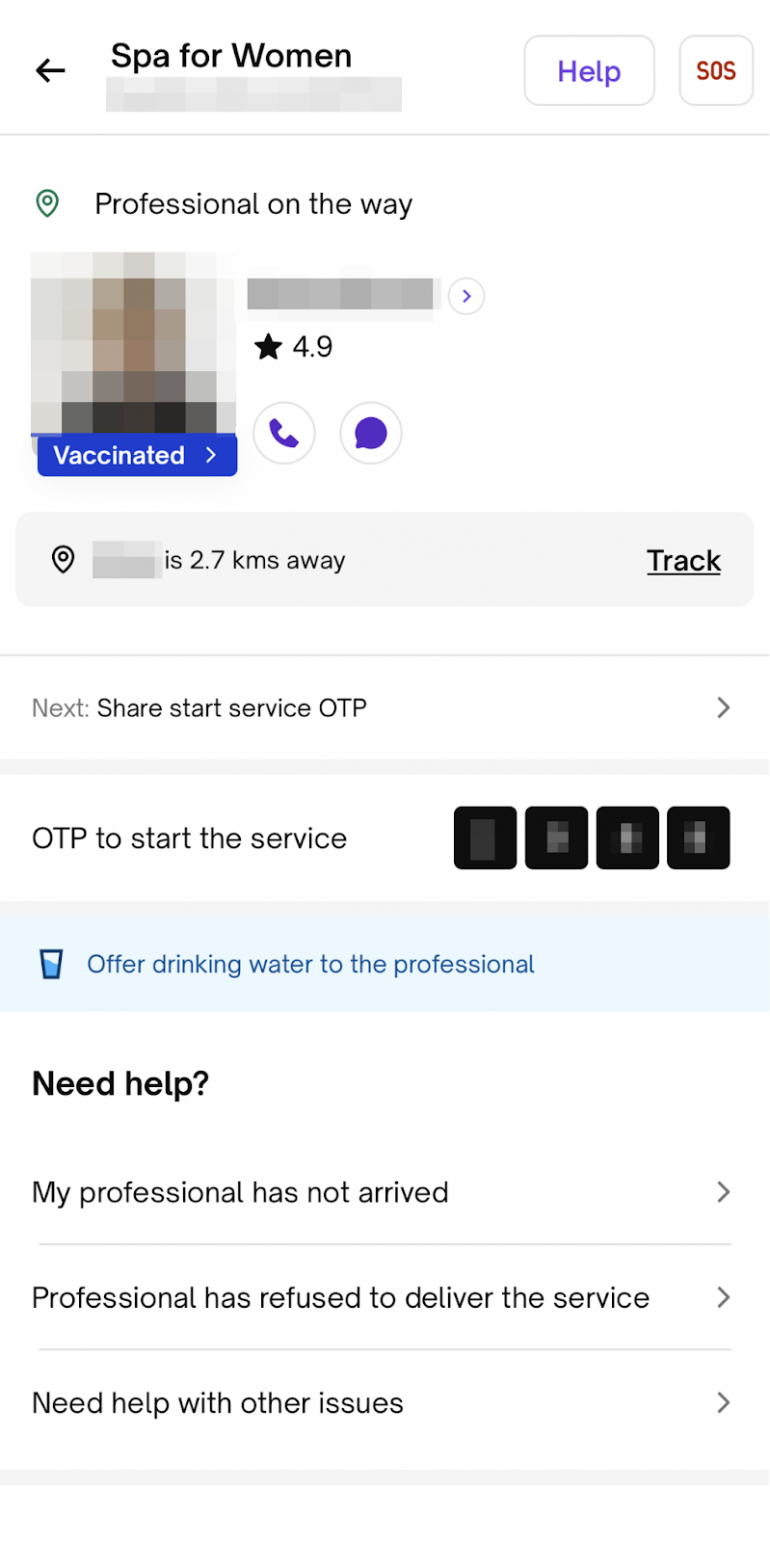

Further, surveillance has been built-in at every step of job delivery to make the customer feel safe. From multiple One Time Passwords or OTPs, real-time location tracking, use of facial recognition and requirements of multiple photographs during the task, the workers have to bear the brunt of the platform’s security theatre. None of the platform’s safety considerations is extended to workers as part of the app design.

The workers are not only supposed to keep up with the customers’ moods during service delivery in order to maintain their ratings on the app, but also have to constantly keep up with unrealistic demands of the platform while at the job.

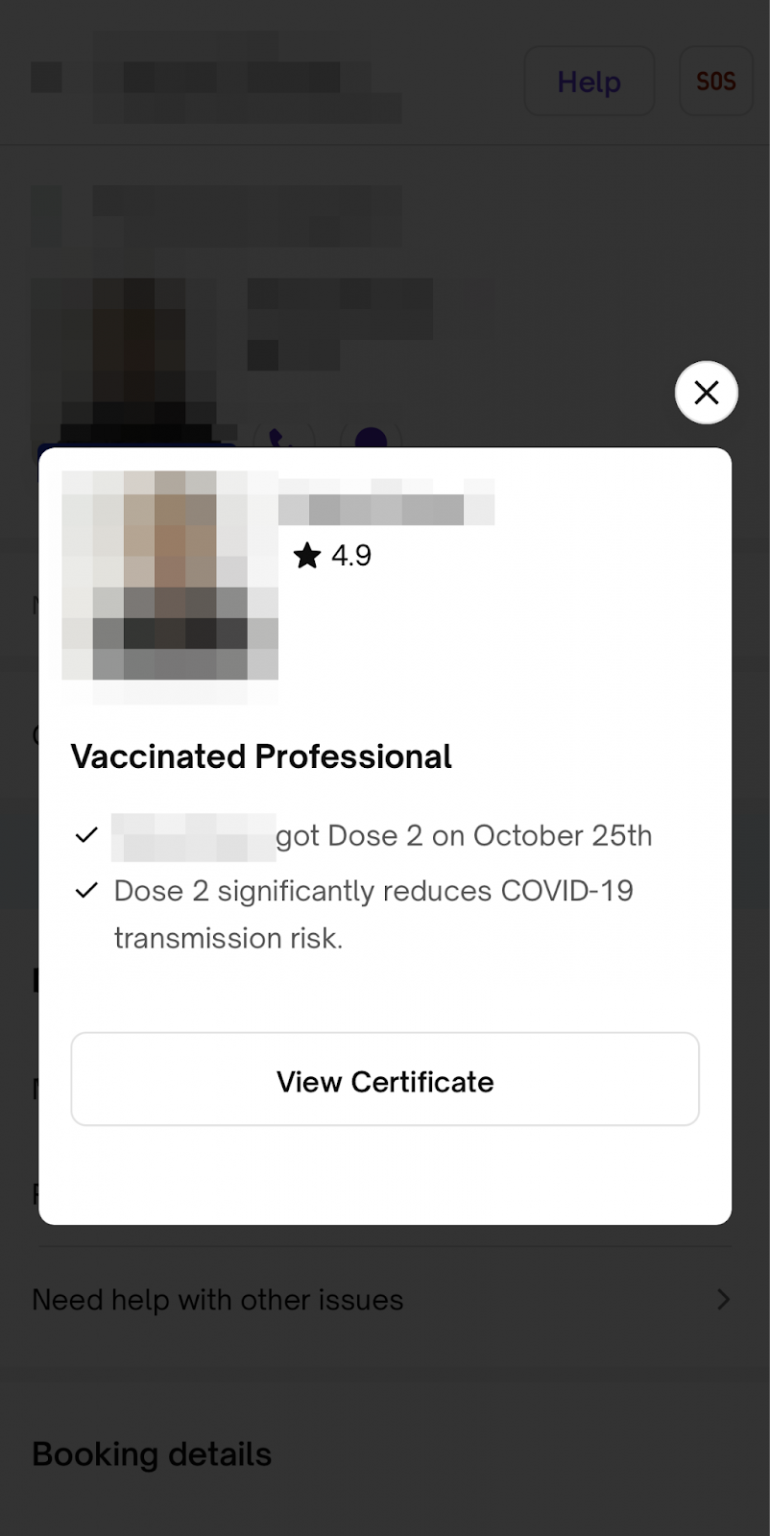

Customer end screen showing workers’ location, and vaccination certificates among other customer ‘safety’ features. Source: Report

Workers told us that they are asked to “trust their intuition” and “not respond back” as tools to handle customer misbehaviour. This disregards the fact that domestic workers are operating in someone else’s household and thus are extremely vulnerable.

“One client I had wanted a haircut outside of the house, while it was raining. The client had to have their coffee, then they needed a table fan as well for the haircut. In such situations, it’s best to get the work done as quickly as possible.” - Ashok, beauty worker.

Workers felt that they are left on their own to figure out their safety, leaving them heavily dependent on a pre-existing support system: some women workers don't take jobs after a certain time of day and others travel with a male family member to the workplace. According to recent reports, workers from religious minorities are increasingly using pseudonyms to avoid rejection and mistreatment. Due to the penalties for rejecting potential jobs, workers often don't have a real choice in avoiding customers that make them uncomfortable.

“Sometimes [the customer] will give the location of one place and live at some other place. They come to pick me up at the location. So it’s very difficult. That’s why I don’t accept jobs in [locality name]. It displays in my list also and it [declining] does not look good.“ - Ananya, home chef.

Support and Collectivisation

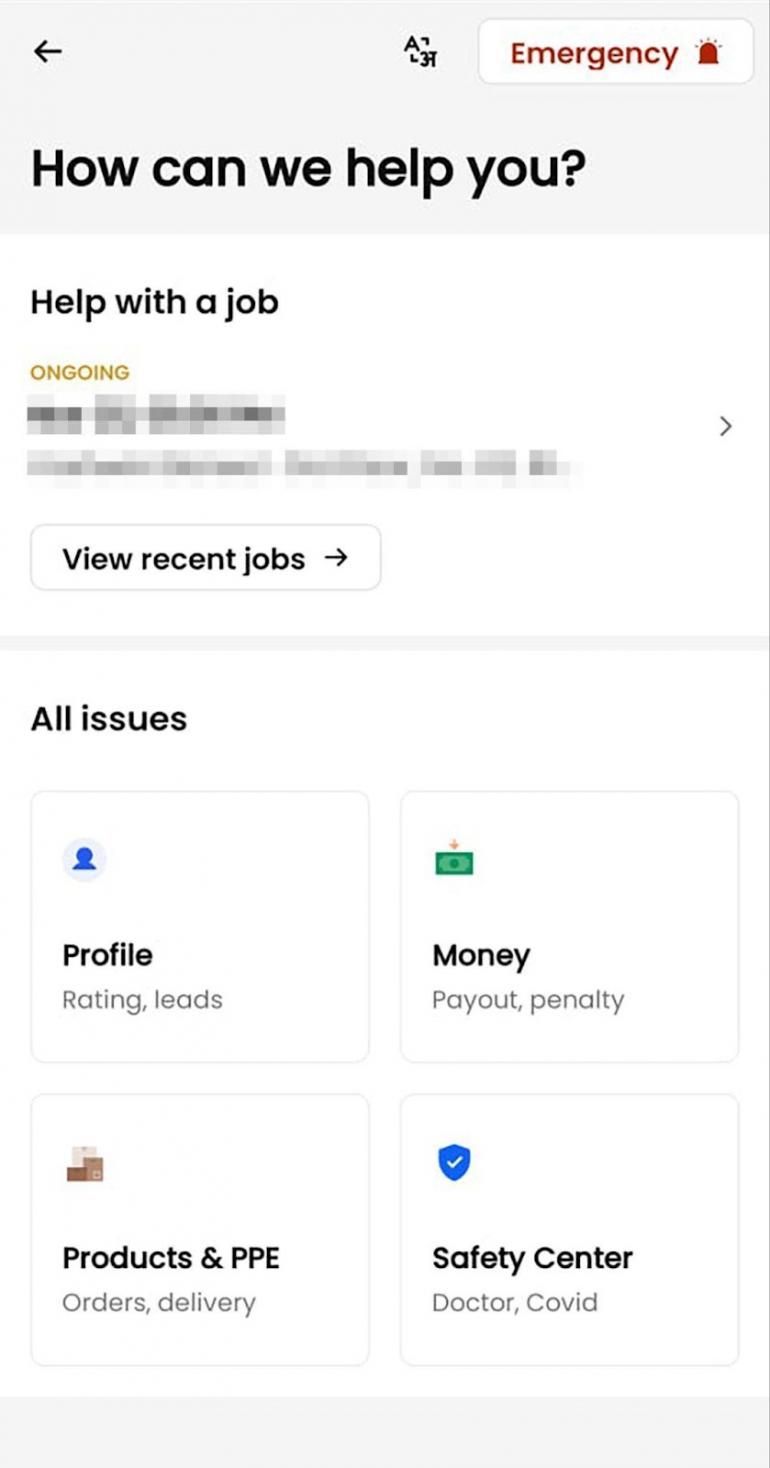

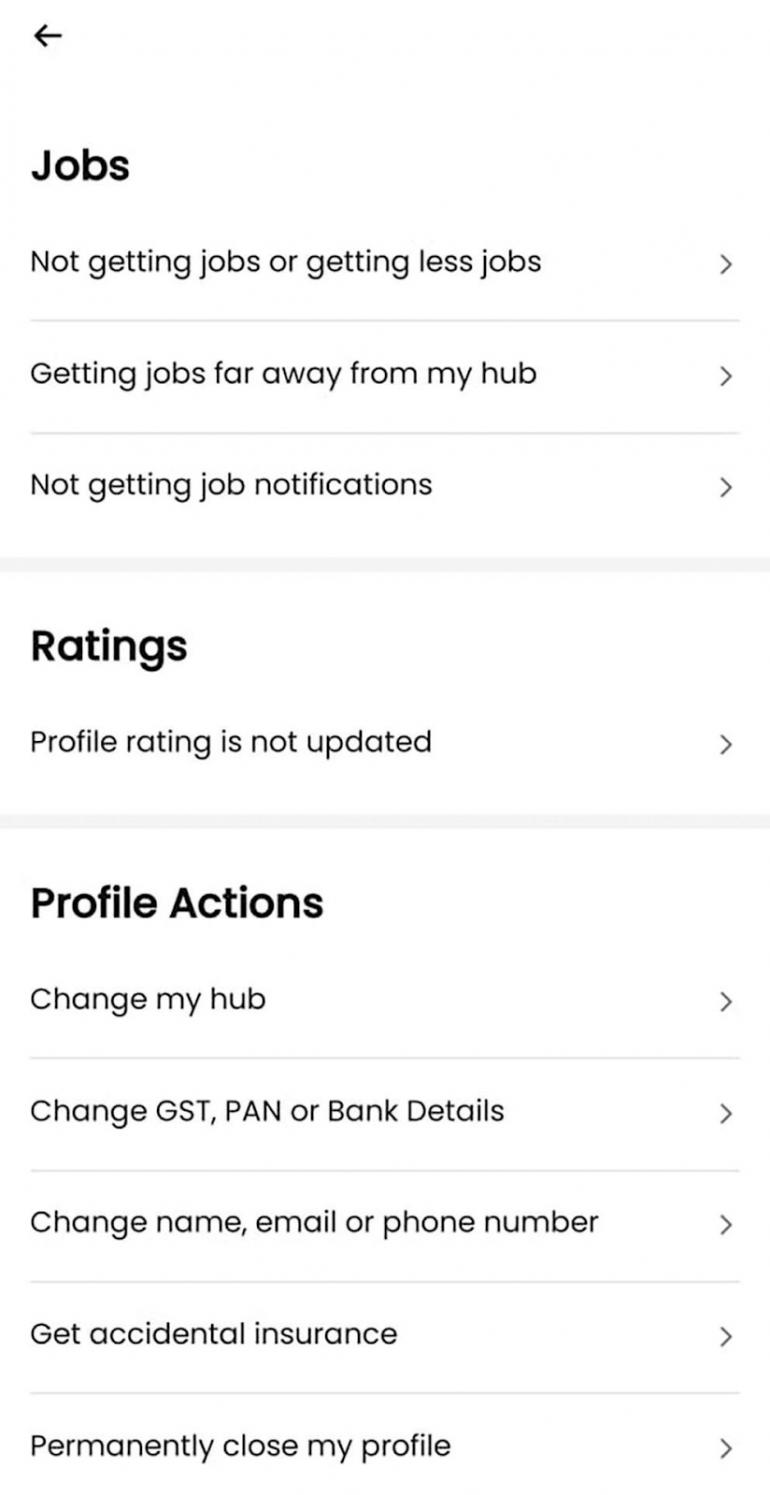

While platforms like UC, Swiggy, and Zomato are very proactive to respond and address customer complaints on calls, on social media and press, no such effort seems to be made for workers. The help section within the UC app is inadequate, and the helplines provided and managers responsible are unresponsive in times of urgent need.

While a FAQ-style help centre exists, it is inadequate for workers. Source: Report

“It’s like you are going and ringing the doorbell, and get to know that [the appointment] got cancelled. Someone opens the door and says that it has been cancelled. It makes me very angry.[…] But they [UC] don’t listen to you even if you tell them. This is the funda [principle] of every company. They only say but don’t do much for it. They always say that they also have to manage a lot of things. Even if I call them and tell them that this madam is saying this or that then they simply tell us to manage. Or they don’t pick up the call.” - Maya, beauty worker.

For workers, the experience of working with the platforms can be extremely alienating, not knowing who they are working with, or where to go for help. Workers don't share a workplace or a common meeting space and platforms do not invest in peer-to-peer communication for workers. While some workers have connected over WhatsApp groups and meet at informal gathering spaces, the platform’s positioning of workers as independent micro-entrepreneurs pits them against each other. The mechanisms like ratings and service categories (classic, luxury, deluxe, etc.) create artificial competition and have implications for worker solidarity. The design of the platform and the individualised nature of gig work hinders collectivisation.

Conclusion

Our research shows how platformisation of domestic work caters to urban upper class, upper caste, English-speaking customers whom platforms consider to be ‘users’. Workers are treated as replaceable commodities not worthy of the same “user” centeredness afforded to their customers. In practice, UC monetises both workers and customers making both parties equal stakeholders in platform functions, this is seldom borne out in practice.

While the design blogs and marketing department present workers as “entrepreneurs” who are “[their] own boss” with full control of their work; the reality is that workers are not their own bosses but governed by the intersecting whims of the customers they service, the company that does not properly employ them, and a technical system that does not acknowledge the realities of the work they do – leaving them vulnerable and alone.

—-

All worker names in this article have been changed to protect the privacy of the research participants.

This article is based on the research "Designing Domestic Work Platforms: A Case Study of Urban Company" conducted by Centre for Internet and Society (CIS) under the Feminist Internet Research Network (FIRN) project of APC. Access the research here.

- 1120 views

Add new comment