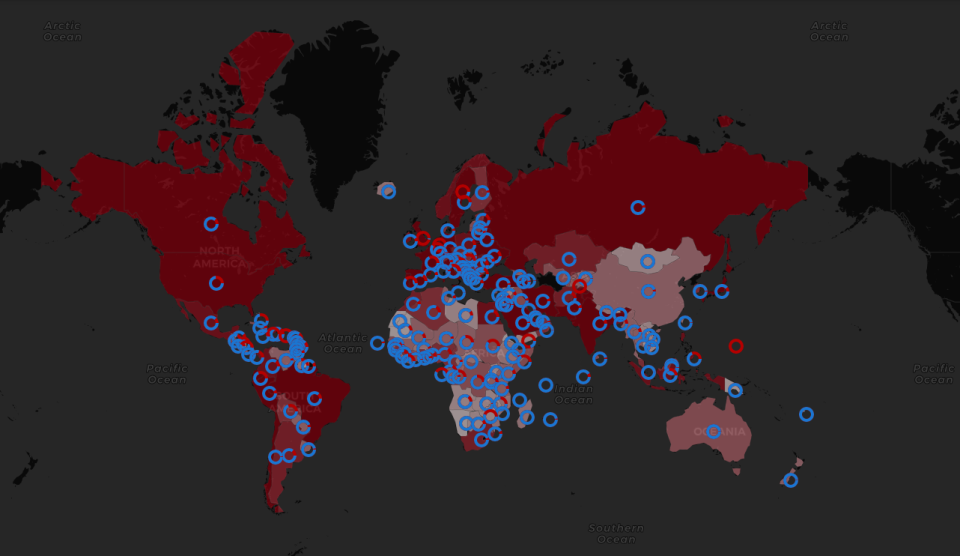

Captura de pantalla de thecoronamap.com

The first weeks of COVID-19 were full of uncertainties. These quickly translated into widespread chaos that served as an excuse for the implementation of state security measures. We all witnessed how, in simultaneous geographies, security measures were imposed as a way of taking care of “each other”. But not all of us witnessed how these measures, far from taking care of all of us, stated a clear positioning of the security model chosen for this pandemic. While making the social inequalities and hegemonic control structures in which we live, visible. The world’s most privileged population (translated as the white middle- and upper-class population) was presented with a scenario of insecurity for the first time. And the response to this was "stay at home", "I take care of you, you take care of me". This imperative command is especially interesting, given that these people, who today demand respect from other people(s), had until now benefited from the global system based on inequality, dis-privilege, and especially the accumulation of power. The rift was more instantaneous than the state of emergency since it does not require an exhaustive analysis to realise that in order to stay at home, I must first have one. And because our powerlessness in the face of this imperative comes out of our pores. Why should I take care of you, white man, if you have historically abused my dis-privilege? You're not taking care of me, you're taking care of you and your people.

Why should I take care of you, white man, if you have historically abused my dis-privilege? You're not taking care of me, you're taking care of you and your people.

The self-production of big data

So far this story is one more in the matrix of modern cultures: inequalities, feelings of belonging and absurd paternalism. But the pandemic in 2020 has brought us a new phenomenon: the self-production of big data. Accompanied by the division between those who manage data to create information and those who contribute their data, while suffering the consequences of it. The quarantine finds those scholars who, because they are working from home, have the time to give back to the world all that the world has given them, and if by doing so they gain recognition, even better. Accustomed to the use of technology, and strongly influenced by our data-driven society, they have begun to generate platforms in pursuit of the “extermination of infectious sources”. This all fits in with the now trendy motto #togetheragainstcorona.

The Corona Map project offers a platform for mapping COVID-19 cases, recoveries, and deaths by country – it currently offers information on 181 countries. Likewise, it offers an infection mapping service. Through an automated form, combining personal data with a series of yes/no questions that subsequently translates into a personalised percentage of possible infection. By accessing your location, it automatically publishes the results in a world map, without prior notice.

Beyond the possibility of manipulating this mapping – e.g. by publishing different results from the same location – in these times of social media, where the private sphere has turned into the public, can we be sure that the data will be entered in the first person? Can we be sure that if “peripheral” areas with a high degree of so-called “infectious hot spots” appear, these will not be isolated by a lack of essential services? How can we avoid, in such a crisis, an increase in violence against those considered guilty of the spread of the virus?

There is no need to imagine this scenario because unfortunately it already exists. The government of India has made available to its citizens a series of tracking apps concerning COVID-19, among which the so-called Aarogya Setu stands out. By using Bluetooth, Aarogya Setu can trace the relationships between its users and calculate the infection potentials that each one has. When a new positive case is detected, Aarogya Setu immediately alerts the authorities of all persons who were in contact with that individual.1 In other words, it grants full authority over the handling of personal data to the state.

While large social media corporations have shown their support for Aarogya Setu, and even agreed to assist in its mass application, the Internet Freedom Foundation has voiced skepticism, arguing that use of such an application could prove controversial when it comes to individual privacy.2 Likewise, legal experts have expressed concern about the manipulation of data and the lack of representation in connection with Indian people’s access to smartphones.3 Nevertheless, the interest in this type of public-private data partnership is so great that Apple and Google are launching their own tracking software, to be tested in four countries, including Germany and Uruguay.4

Beyond all the uncertainties surrounding the questionable management of data and its future uses, this experience demonstrates the very imminent danger posed by the handling of personal data by the authorities and how this leads to increased surveillance and state violence. The Indian press has already reported several leaks from the authorities themselves, including tweets of images and home addresses of people considered “infected”.5 The police have also adopted the practice of identifying quarantined houses by pinning posters on the doors, showing the start and end dates of the quarantine,6 in order to visualise possible sources of outbreak. The manipulation of tests and information made public has been used to increase the Islamophobic discourse, leading to instantaneous hateful reactions within society. At the same time, areas considered to be in danger are beginning to be isolated under data-based excuses. That is, under the narrative of caring for each other, the most vulnerable people lose their freedoms again, institutionally, socially, and culturally. This serves as an example of the violation of peoples through statistics. In other words, statistics are serving as a tool for modern/rationalist/colonial regimes, which seek to single out and locate potential dangers in order to attack them. In this case, infections that must be exterminated.

Areas considered to be in danger are beginning to be isolated under data-based excuses.

The peculiar and dangerous confusion of information and data

These are just two examples of how the practice of mapping was successfully enshrined within a month among the world's middle classes as a means of rapid visualisation. Day by day, different social projects appear in our – currently single – digital space, seeking to offer data in real time. You may ask, am I against social projects? Does it bother me that people are trying to help? The answer is not simple and requires at least two conceptualisations. First, the differentiation between information and data. Second, the notion of anticipation.

In current times there is no longer any need to explain the relationship between knowledge and power,7 and how this has shaped the management of digital information, as mostly reacting to standardisation structures. This can be explained through the peculiar and dangerous confusion between information and data, which the era of mass digital communication has promoted.

For Sheila Jasanoff, professor of science and technology at Harvard University, the relationship between technology and knowledge is closely linked to the categorisations derived from scientific-rational thinking. Jasanoff argues that by giving science a hegemonic role in knowledge creation, it has managed to control participation in this process. This has caused a lack of representation, but above all, a lack of autonomy in the use of knowledge in the form of information, since knowledge – as a political structure – determines belonging.8 Belonging to the elite that constructs the information, or belonging to the margins on which data is obtained for the construction of such information.

In this scenario, Jasanoff sees the co-production perspective "as a way of encouraging conversation with other approaches to political and social research."9 In other words, in a co-production model, the different agents related to knowledge have the opportunity to participate and contribute data that integrates their existence into the creation of information, thus bridging the gap between information, knowledge and societies.

The second step of my conceptualisation is the notion of anticipation. It comes from one of the most ignored design theories: Comprehensive Anticipatory Design, by R. Buckminster Fuller. This theory assumes that all human actions imply a design process, and likewise, they all generate consequences in the cultural formations in which they actively participate.

Roughly speaking, this theory suggests a series of exercises and reflection aimed at evaluating the potential of our ideas or designs. First, introducing systemic thinking, that is, noting that a product of design cannot be understood as something isolated, but as a component of a system. As such, it requires an understanding of the different interactions surrounding an object. Second, anticipating its role in that system, and therefore, its influences on it, whether positive or negative. That is, reflecting on the cultural and social modifications that the design will generate, via a detailed analysis of the problem-solution relation in which it is meant to be inserted.

In other words, anticipation is neither a scientific form, for which a laboratory is required, nor a purely academic form of knowledge. Anticipation is taking the necessary time for reflection before releasing an idea that might otherwise not even advance the interests which we aspire to. On the other hand, we can look at it from the perspective of the construction of spaces of dialogue and co-production (subscribing to Ingold's anthropological perception)10 where different ontologies converge. Ergo, everyone has access to the same space in the decision-making process, but above all in the analysis of the real problem, in order to be sure that the solution proposed meets everyone’s needs.

When we apply both concepts to the unfolding pandemic, in a world that is guided by standards-based technologies, one division becomes clear: you are either a helper or you are helped. This division, which seems to naturally exist, exposes one of the greatest control structures of modern societies: the oppressed-oppressor division of colonial processes, which seeks to perpetuate control over the global South through cultural valorisations. These valorisations have historically tilted the balance toward Western rationalism as the path to development,11 based on the notion of standards as the foundation for understanding a universal way of being human. Serving the positioning of the white man at the centre of the creation of such standards, and reducing our pluriversality to the existence of the privileged class. Just think of the case of India, and the increase in social violence.

In a world that is guided by standards-based technologies, one division becomes clear: you are either a helper or you are helped.

A more just approach to information-based aid

Why analyse helping so much if the important thing is to help? Because giving help does not necessarily mean that we are helping – or at least not in the way that we believe. Let's consider the Corona Map project or Aarogya Setu. Both projects rely mostly on the existence of mass data but not on information – that is, the availability of data that can be used without the knowledge and consent of individuals. Through massive use of technologies, this historically constructed cognitive logic has managed to position the notion of personal data as a resource. Thus, the asymmetry of power has increased through the handling of this data when it is converted into supposed information.

This reinforces social inequalities that do not allow us to navigate a path out of the pandemic that is egalitarian and safe for all peoples. Such asymmetry is deepened by standards that give the elites not only the authority to define those people rendered vulnerable by the system as outside the norm, but to force them to accept their aid – “aid” to achieve a set of values determined by the same elites as correct, and which the capitalist system will never let all the people(s) achieve.

Within the current landscape, we could argue that a more just approach to information-based aid would be one in which all people have the autonomy to share or not share their situation – i.e. to contribute or not to data banks. Autonomy to choose to ask for help or to provide help, but above all, autonomy to accept, or not, to receive help. This autonomy can only be achieved if we leave aside the use of technologies that reproduce class disparity, gender inequality, and cultural oppression. This requires a restructuring of helping spaces, whether they be state-run, private or even social spaces that unwillingly reproduce the paternalisms that modern states have managed to perpetuate.

This autonomy can only be achieved if we leave aside the use of technologies that reproduce class disparity, gender inequality, and cultural oppression.

In the era of communication, we are so used to big data that we tend to see its positive potential while losing sight of the possibility of accessing information without data. How to take care of ourselves? Where to take care of ourselves? Who to ask for help? That is information. Who should we take care of? That is data based on a colonialist conception of society, which has historically divided us between those who devise aid and those who receive aid. The only thing that remains to be added, then, is that if we do not get off the map that represents hegemonic political interests, we will continue to be inserted into the structure of the oppressor and lose agency over our ontologies.

Footnotes

- 1. https://citizenmatters.in/tracking-quarantine-tracing-cases-sharing-info...

- 2. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/software/government-requests-s...

- 3. https://indianexpress.com/article/business/legal-experts-raise-concerns-...

- 4. https://www.teledoce.com/telemundo/ciencia-y-tecnologia/uruguay-fue-eleg...

- 5. https://citizenmatters.in/tracking-quarantine-tracing-cases-sharing-info...

- 6. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-52201706

- 7. Foucault Michel, 1979, “La arqueologia del saber”, Siglo Veintiuno Editores, Mexico

- 8. Jasanoff Sheila, 2015, “States of Knowledge. The co-production of science and social order”, Routledge, USA and Canada

- 9. Idem 8

- 10. ngold Tim,2015, "One World Anthropology",McGill University, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iEWS89dd9nM

- 11. Quijano Anibal, 2000, “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America”,Nepantla: Views from South 1.3, Duke University Press, USA.

- 12010 views

Add new comment