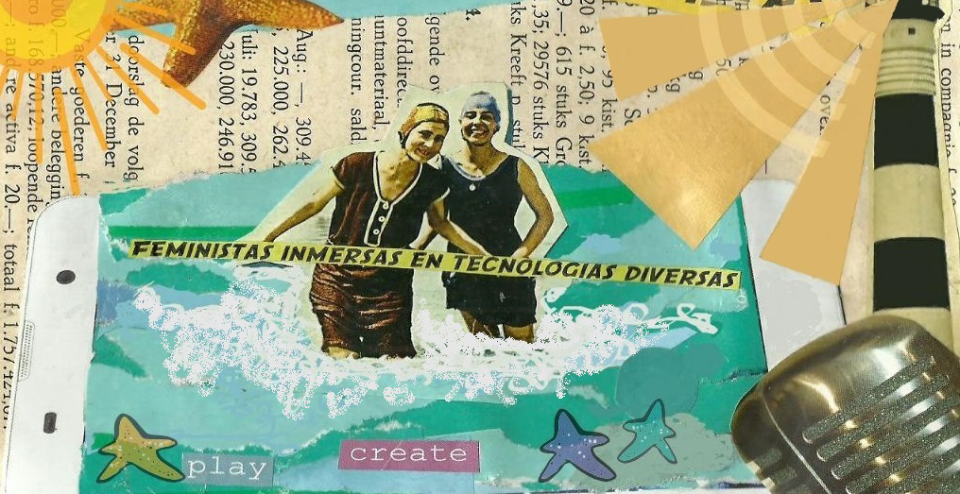

Feminists immersed in diverse technologies (collage): Original artwork by Flavia Fascendini

Interpreting the internet: Feminist and Queer Counterpublics in Latin America by Elisabeth Jay Friedman is a grounded and well thought-out book. It is essential reading to anyone new to feminist counterpublics in Latin America, and I suspect to many feminist activists who may want to contextualise the work they do online.

It is also more than a book on feminist counterpublics, and will be of interest to general readers curious about how counterpublics can be formed by appropriating whatever technology is available – from print, to the humble photostating machine, to the internet – to shape their world making.

Friedman is a professor at the University of San Francisco with a long-standing interest in both gender studies and Latin America. Her book is the result of fieldwork in the region: some 125 interviews with feminist, women and LGBT activists in 2001 and 2002 and between 2009 and 2013. This means her research straddles important shifts in the evolution of the internet – from the use of simple websites and mailing lists by feminists in the early 2000s, to the later proliferation of internet access and active use of social media as an advocacy tool. Friedman says this helped her “estimate the extent to which the internet was changing, and being reinterpreted by, the organizations and people who made counterpublics possible”.

Friedman’s book is the result of fieldwork in the region in 2001 and 2002 and between 2009 and 2013. This means her research straddles important shifts in the evolution of the internet – from the use of simple websites and mailing lists by feminists in the early 2000s, to the later proliferation of internet access and active use of social media as an advocacy tool.

The strength of Interpreting the internet is the scope of the timeline. The results of her fieldwork are placed in the context of the rise of feminist literature in Latin America as early as 1873, with the publication of the Brazilian women’s periodical O Sexo Feminino, and, also in the late 1800s, La Mujer in Chile and El Aguila Mexicana in Mexico. Later, in the 1970s onwards publications such as fem and mujer/fempress, and CIMAC, a feminist news service, emerged. “Latin American feminists,” she writes, “increased the numbers and stability of their publications by taking advantage of then-new technologies”. These new technologies included the Xerox machine, and some 200 copies of the first editions of mujer/fempress were photostated, before funds were available to circulate printed copies regionally in the mid-1990s. These publications, Friedman says, show that “activists during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century…developed strategies to name and claim women’s rights long before the advent of the internet”.

Equally important to the circulation of feminist publications in the region were the Latin American and Caribbean Feminist Encuentros. Started in 1981, these face-to-face meetings allowed feminists to “articulate their own identities” and “debate – often furiously – the meaning and goals of feminism; and strategize for transformation across the region.” Reflecting the region’s “diversity and divisions” amongst feminists – a characteristic quintessentially Latin America – the encuentros “provided a space for exchange across difference, exchange that could lead to discursive and organizational innovation”.

Book cover. You can buy the book online here

Friedman offers a very useful account of the early evolution of internet access in the region when activists began building civil servers in the mid-1980s onwards: AlterNex in Brazil – the first non-academic provider in Latin America, and brazenly set up under military dictatorship using the state telephone service (the company “did not completely understand what AlterNex was doing”), Chasque in Uruguay, Nicarao in Nicaragua in 1989, INTERCOM-Ecuanex in Ecuador and LaNeta in Mexico in 1991, and Wamani in Argentina in 1992.

The potential of the internet to create inclusive spaces for exchange for feminists was first suggested by Hotline International, a rudimentary telephone-to-terminal network with focal points in the United States that connected activists who could not attend the 1975 International Women’s Year conference in Mexico City. Because of its limitations in reach, however, Friedman finds that Hotline “reinforced the elite nature of international negotiations even as it expanded participants beyond those who could physically attend [the conference]”.

Instead a watershed moment occurred at the 1995 UN Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing where the Association for Progressive Communication’s (APC) Women’s Network Support Programme (WNSP) set up an on-site civil server.

The WNSP server provided free emails accounts to delegates, allowing them to communicate and share information beyond Beijing. Friedman writes vividly of the event: “In a modest building, a few rooms were filled with rows of desks topped by boxy screens and keyboards. Cables snaked across the floor. On a typical afternoon a Mandarin-speaking Women’s Programme volunteer would be teaching a small group of Chinese women how to use the email on one side of the room, while two Brazilians attempted to access their messages on the other.” The intervention was so successful that even the media started using the WNSP’s internet access – some 62,000 emails were sent and received during the conference.

In a modest building, a few rooms were filled with rows of desks topped by boxy screens and keyboards. Cables snaked across the floor. On a typical afternoon a Mandarin-speaking Women’s Programme volunteer would be teaching a small group of Chinese women how to use the email on one side of the room, while two Brazilians attempted to access their messages on the other.

In Beijing, Friedman writes, “[w]omen saw how the internet could help them with a central task of their own counterpublics, the formulation and distribution of information outside of governmental and mass media channels”. For example, Modemmujer, a recently founded organisation in Mexico, facilitated the redistribution of conference reports received via the on-site server to some four hundred additional email addresses, which in turn were shared using “fax, local newspapers and community radio”.

Interestingly, Friedman finds one of the clearest examples of the positive use of the internet for sustaining feminist counterpublic formation in the simple mailing list. She dedicates a chapter to the Red Informativa de Mujeres de Argentina (RIMA), which was set up in 2000, making it one of the oldest national feminist mailing lists in the region. In this list, Friedman finds “a space that cannot be replicated offline”, providing an “avenue for encounter that can be accessed according to members’ wishes, when and where they want to be comforted, challenged, or championed.” Although RIMA’s Facebook page attracts some 11,550 followers compared to the list’s 1,200 subscribers, social media did not allow the same level of “identity construction and exchange” as the list.

Inside pages of the book

Friedman offers a critical perspective of the use of the internet by feminists, arguing that the positive use of the internet for social change depends on shifting social contexts, and that the strength of the use of the internet – like any technologies – depends on its conscious and creative use to bring about social change. She argues that the internet is “no more inherently queer than it is inherently feminist”. In itself, the “internet offers no guarantee for social transformation”, and can been shown to reinforce social inequalities and create new forms of exclusion.

The internet is “no more inherently queer than it is inherently feminist”. In itself, the “internet offers no guarantee for social transformation”, and can been shown to reinforce social inequalities and create new forms of exclusion.

Latin America itself is an important socio-geographic region to explore. It was, she writes, “a region ready for a technology of connection and diffusion”. While “°ther regions and other activists have had similar experiences”, Latin America was in a unique position to take advantage of the internet: “In no other region of the Global South were so many ‘early adopting’ technical skilled organizations ready and eager to get such deeply regionally connected counterpublics online.”

Friedman’s use of counterpublic theory as a frame for analysis – which asserts that fields of circulation of texts are critical for the formation of counterpublics – is a natural fit. Drawing on Lincoln Dahlberg, she says the internet appears to be particularly suited to respond to three key characteristics of counterpublics: “building identities, creating community based on new ways of thinking, and strategizing for change”. She provides a brief introduction to Jürgen Harbermas and Nancy Fraser for those unfamiliar with their work.

Friedman says the internet appears to be particularly suited to respond to three key characteristics of counterpublics: building identities, creating community based on new ways of thinking, and strategizing for change.

Although Interpreting the internet is based on fieldwork and a clear research methodology which Friedman outlines in the introduction, it is a comfortable and easy read – it is not a “research report”. Having worked with APC and its members over the years, there are a number of familiar names here – work colleagues Erika Smith, Daphne Plou, Jan Moolman, Jac SM Kee, Valentina Pelizzer, amongst others, and organisations such as Nodo Tau, LaNeta and NUPEF. I also found moments of beauty in her research methodology, such as when she writes: “I found myself scanning the bounced-back email messages, broken hyperlinks, missing websites, and stalled social media efforts where digital trails disappeared. Because internet technology gains its meaning through use, its departure also tells a story worth listening to.”

I also found moments of beauty in her research methodology, such as when she writes: “I found myself scanning the bounced-back email messages, broken hyperlinks, missing websites, and stalled social media efforts where digital trails disappeared. Because internet technology gains its meaning through use, its departure also tells a story worth listening to.”

- 4911 views

Add new comment