Caroline Tagny interviewed Rohini Lakshané, who used to work with EROTICS India, and Sheena Magenya, from the Coalition of African Lesbians during the Global meeting on gender, sexuality and the internet in April 2014 to ask them how they understand pornography from their respective contexts, and how do they engage their activism with the intersection between sexual rights and internet rights.

Caroline Tagny: Should we start by introducing ourselves?

Rohini Lakshané: I set up and ran the EROTICS India website. I worked with EROTICS India from October 2013 to May 2014. Apart from running the website, the EROTICS project in India also engages with people offline. We’ve done meetings in 5 big cities in India with policy makers, activists, NGOs, lawyers, media people, bloggers, academia, students etc. who work on gender rights, sexuality rights and internet rights, and brought them together to discuss issues in the intersections of these topics and we are really the first people in India to have done this, to have brought people together and start a discourse on the intersection of those 3 topics. I was working as a technology journalist covering ICTs for development, online civil liberties, technology for good, etc, so a part of the EROTICS India project overlapped with my previous work. I had also been working on gender issues in a volunteer capacity. I chair a group called Gender Gap at Wikimedia India, which aims to bridge the gap between the genders on Wikipedia. There is a 9% female participation on the English language Wikipedia this is according to a survey conducted by the Wikimedia Foundation in 2011. The sexuality part of the project was new for me.

Sheena Magenya: I am the media and communications manager for the Coalition of African Lesbians. It’s a regional representative organisation, with over 30 organisations represented across 19 different country in East and Southern Africa. What we do is we lobby various advocacy spaces on issues of, what we like to call, gender and sexuality. Because our contextual analysis of the situation for so-called gender and sexuality minorities or LGBTI people is that our problems are bigger than just being lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex. Our problems are issues of economy, issues of poverty, issues of agency, issues of autonomy. And that’s why we are sexuality and gender advocates in Africa.

CT: How do you see the internet intervening in the work you do now?

SM: If we look at how to connect to our members, the internet is the most efficient, effective, accessible way for us to maintain contact with our membership and send out information. CAL is also a member of the Women Human Rights Defenders Coalition, therefore for emergency responses and such, the internet is like the most fast and effective way to ask for help and send help. Even money transfers or whatever a women’s human rights defender might need in that time. So it is very convenient, and it is very instrumental in how we communicate with our members, within the organisation, with our partners, donors, funders… The internet and communications are impossible to separate, it’s a very pivotal part of the work that we do.

Flavia Fascendini: As gender and sexuality advocates, do you have a reflection or an analysis about the interaction between sexual rights and internet rights? Is it part of your analysis or your framing?

SM: In a way it is, because we as an organisation that has a relatively strong online presence, we do challenge things around for instance internet misogyny, because that replicates and represents itself in so many spaces, even in the gender non conforming queer spaces in Africa, where we find that there is a lot of sexism, that different sexual identities are playing around each other. But we haven’t had for instance a specific program that addresses just that. And I don’t think we have entered a conversation specific to the internet, how we interact with it and the effect that it has on the influence especially on popular culture and popular beliefs around gender and sexuality of Africans.

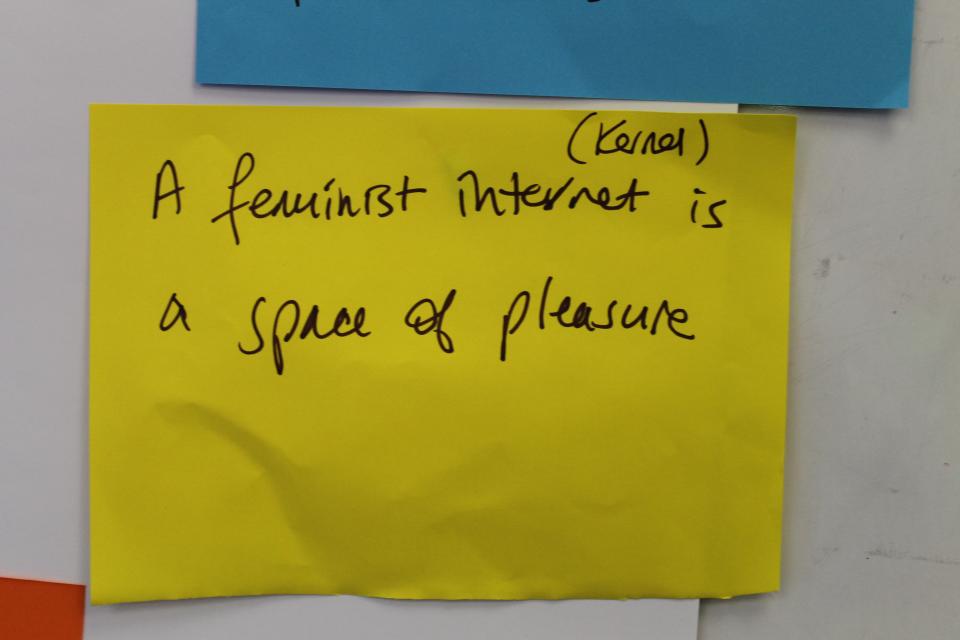

CT: How do you imagine a feminist internet?

RL: A feminist internet is one in which people of all genders and none have equal access. They have not only equal inclusion but equal presence. Having physical access to the internet, or physical access to technology is not enough. It is important for all genders to have a voice and a presence online, but obviously it is currently skewed the way it is in the offline world.

SM: My vision is, in the context of eastern and southern Africa and in understanding that there’s a variety of socio-economic issues that women are dealing with, the internet could be a practical tool, a conduit for solving some of these problems. If saying that a women having access to the internet meant that she would have access to better contraception, if women access to the internet meant that she would have better access to protection, to safety, to security, to information around sexuality and gender, sexual and reproductive rights, for that is a feminist internet. It needs to have a practical living purpose in solving problems that women are dealing with.

CT: I’d like also to talk about porn. What do you see as a challenge in terms of sexual content online, that can be deemed as pornographic? In both contexts that you are working in, how does that influence the work of activists? How does that influence in general women like you in seeking pleasure and entertainment online?

RL: The biggest problem with pornography is that it is difficult to define, and has not been legally defined. One person’s erotica is another person’s porn, another person’s high art is another person’s obscenity. And when there are restrictions and safeguards implemented on the internet to prevent the proliferation of certain kinds of porn, or to prevent certain sections of the society, let’s say children, from accessing porn, it also then threatens to filter out other things such as the sexual expression of women and the sexual expression of sexual minorities. As activists, it is very important for us to watch out for censorship of women’s writing, feminist writing and sexual expression in the name of pornography. Sexual expression online often involves backlash, which causes people to self-censor. We should be vigilant against what constitutes pornography to governments, to the law, and to ‘public-spirited’ people who try to define and decide what other people should watch.

SM: I think with our situation, the biggest challenge is people not wanting to even have that conversation, people refusing to acknowledge that there is pornography. There is African pornography, because there is always that west-south thing where people say “that’s a western thing” but it isn’t. There is locally made pornography. And also shifting the conversation away from the idea that all pornography is abuse, because there is also that going on, that women who do voluntarily, in may cases, take part in, or participate in the making of pornography are doing that with the full knowledge of what they are doing, with full agency. And these are African women. People refuse to have that conversation. So even having that conversation and putting it in the face of decision makers who always try to moralise everything, the moralisation of morals even. Everyone is trying to be the most moral state in Africa.

FF: So there is a lot of hypocrisy.

SM: It is hypocritical, because it’s deeply consumed. And this is not just in Africa, this is in the world. This is also in the context where the assumption is that we don’t have access. We do have access, but what are we using the internet for, we are using it for porn. Porn and cat pictures!

RL: These trends of what people are looking at in different parts of the world are sometimes a reflection of what they are being deprived of online. A lot of teenagers go online to look up information about sexual health and contraception because they have difficulties talking to their teachers and parents. Which drives up these online search graphs, and which is why you would see, it often related to the kind of information and the kind of entertainment they are deprived of offline. Another thing about pornography is that, very often, buried under the assumptions and presumptions of morality, propriety and illegality, is the woman’s consent in viewing porn or in acting in porn. If a women consents to model nude on a magazine cover it’s her body, her choice and her life. On the contrary, someone who has been clandestinely shot in a private act obviously does not consent to the shooting or publishing of such content. This is something that people who want restrictions on porn do not consider, especially in countries such as India where topics such as sex and sexuality are taboo.

CT: I think it’s also because the perception of our consent is not ours. So the consent must come from the husband, from the father…

RL: That’s the whole thing, women cannot decide for themselves because they don’t have the power or agency to. Women are not allowed to make decisions – and this applies to not only pornography or sexual activity – because they are considered incapable of it.

FF: There is also a very deep level of internalisation of patriarchy. So even having access to porn, and even daring to say “ok, I watch this”, there is this fear of liking it, or realising that we are being turned on by another women’s acting. How do you process all that, when your head is still framed under moralism and old fashioned values?

RL: That is how gender stereotypes play out. A man is supposed to have a nice, big collection of porn, and a woman is not supposed to watch porn. I think that’s what needs to be broken. On EROTICS India, we have published content about gender and its relationship with porn. At a personal level I have tried to do that, because I used to watch porn as part of my work at EROTICS India.

SM: Do you watch porn in your private life?

RL: Yes. I used to watch porn as a part of my research on amateur pornography. I reviewed The Savita Bhabhi Movie, India’s first animated porn movie for Erotics India and posted on Facebook that my job is swell and that I get to watch and review porn at work. I shared the URL of SavitaBhabhimovie.com on Facebook, which it did not allow. Facebook has banned the posting of any link directly associated with the porn comic or movie. But at a personal level, I have been doing this, and most of the responses have been from men. Some privately messaged me, “you are one of the unique cases where someone is getting paid to watch porn”. So I replied, “yes, I am planning to buy a new 1tb hard drive because I am having trouble keeping it all together!”. I have been trying at a personal level trying to break the stereotype that women don’t enjoy porn.

SM: But it’s a certain type of women. You have those associations, it’s only a certain type of women.

RL: It is assumed that a woman who watches porn is fast, and loose, and easy. At a personal level, I have been trying to assert myself and say, “Look, I watch porn and I make no bones about it, and I am still not a fast and easy woman. And going by the kind of responses that I have been getting, people have taken it in the right way.

FF: It’s such a huge debate. There are many feminists that talk about these kind of issue in terms of exploitation, and bias perspective. One more question, about the language and the concepts behind it. People use the word porn for a lot of different stuff, like child porn, revenge porn… How is that used in your context? Are activists aware of if they are replicating or not those concepts?

SM: Even sometimes just having what feels like a basic conversation on sexuality and gender, or sexuality and reproductive rights, or just sex, like you are crossing a big line, without even having a conversation about porn. But I do agree that people throw it around because right now, in Uganda they have an Anti-pornography Act, but their legislative understanding of what pornography is is ridiculous. In Uganda, the pornography is me showing cleavage. Pornography is now synonymous with any kind of what they consider “moral indecency”. Short skirts. And again, targeting only women. So women are, because women are the gatekeepers of morality, therefore women who present a certain image that is not in keeping with of what the moral standards are, are participating in what is considered to be pornographic act. So just having, which something I think I should take back, is to talk about porn, to talk about pornography, What is that, and why to we keep reappropiating it to all kinds of other things without giving it its context and its space, and having an open, honest, frank conversation about what do we understand porn to be? What are we misunderstanding, and what powers are we giving the word, and what powers are we taking away from the word, and how do we reappropriate this word?

FF: When we think about child porn or revenge porn it still comes down to blaming the child or blaming the women who got her video stolen, and that’s not porn. Those terms are flourishing everywhere and they are catchy so people adopt them.

SM: It’s not porn, there is no consent. Like the term corrective rape that is flying around in Southern Africa, it is crazy. What do you mean by corrective rape? Is there uncorrective rape? What does that mean, rape is rape? Is there good murder and bad murder? When you change languages to suit a context, you have a miscommunication.

RL: I believe pornography in itself is ill-defined, legally or otherwise. Then we have a lot of terms such as child pornography, amateur pornography and revenge pornography that are even fuzzier. For example, in terms of child pornography, how would you define a child or what constitutes child porn? Would the photo or image of a naked child playing in the park be pornographic? There is no recognition of these complexities in the first place because there is no recognition of the nuances around porn. Revenge porn is not even called that in India; it’s called “sex scandal”. There are laws to deal with revenge porn in India – circulating a woman’s videos or pictures without her consent or capturing images in a place where the person shot has a reasonable expectation of privacy is punishable by law. But there is very little understanding and recognition of the existence of revenge porn, of this new kind of so-called pornography which is very rampant in India.

There’s a long way to go before these issues are addressed in any way. I believe as activists it is our responsibility to bring these issues to the fore, from the point of view of tech, sexuality and gender. A lot of content, including sexual expression, is censored in the name of pornography while things such as revenge porn slip through. At EROTICS India, highlighting the problem of non-consensual amateur porn is something that we did from early on, and we are very proud of. We were the first people to have brought this whole phenomenon to the fore and started a conversation about it.

CT: Thanks to both of you!

- 10567 views

Add new comment