This article explores marginalised desires and the need individuals have to express these desires online, especially when it may not be safe to do so offline. Attention is brought to the need to protect individuals’ rights to engage in sharing content and expressing their desires online; and the need for digital security to protection their data and identities. The article also discusses notions of identity, community and the need to form safe spaces (including the need to report violence experienced online).

Desire is the feeling of wanting or wishing for something, in the case of this article desire is considered as the wanting or wishing for sexual gratification or exploration around a need or drive. This is a very open definition that allows room for sexual fantasy and/or practice around a desire or need.

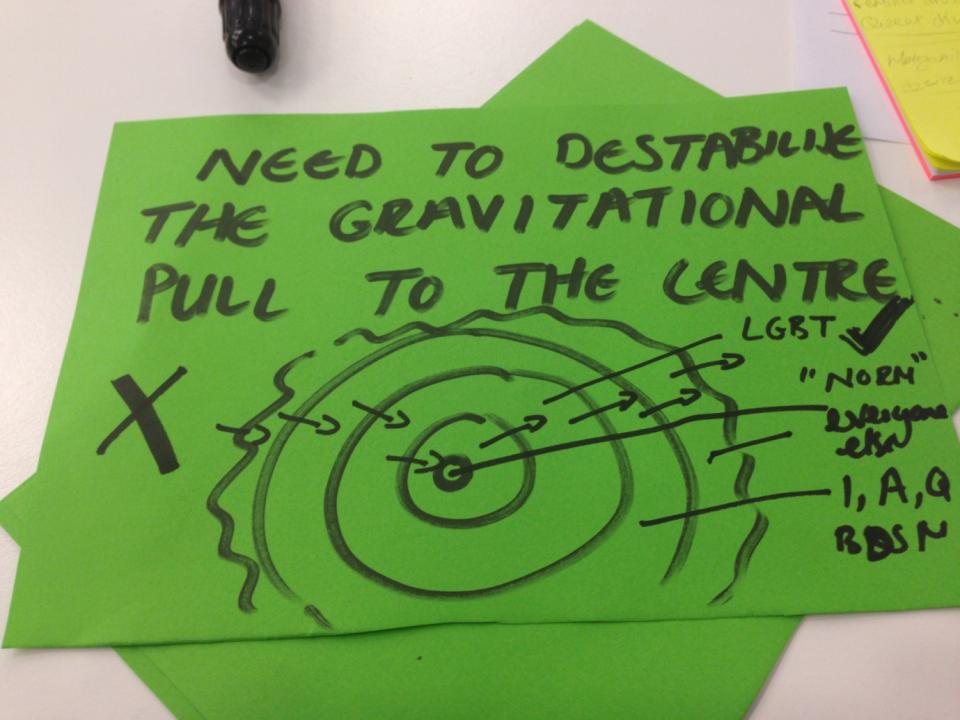

A marginalised desire is any desire outside of the ‘norm’ or centre. The centre is where heteronormativity and vanilla (1) desires lie, just outside of it exists the sprinkles of same-sex desire, which is increasingly becoming part of the centre. The lesbian and gay movements have worked very well at assimilating themselves with the heteronorm and now own their own homonorm while distancing themselves from trans and queer desire. Outside of this homonorm is where the extra toppings (and bottomings) can be found, on the margins.

What constitutes desire and what constitutes harm?

There can be confusion around what constitutes desire and what constitutes harm. Too easily are all desires grouped under harmful desires. It is important to note that simply because a desire makes one uncomfortable, does not mean that it is necessarily harmful. For some homosexual/same sex desire; polyamory; BDSM are uncomfortable desires to begin thinking about, mostly because it brings their own desire into question. Please watch a wonderful talk by Alyssa Royse titled Your sexuality for more on this. Ethical, respectful and consensual sexual activity between two or more adults does not constitute harm, and the spaces where these desires are played out should be protected – online and offline.

When a desire or activity is not ethical, respectful or consensual, then it can be considered harmful desire and/or behaviour. Consent is significant here because some may argue that consent can be given by minors, for instance – this is a very grey area. In my personal opinion, minors are minors, and a person under the age of 18 cannot be expected to give informed consent. From my position I would argue that sexual activity with minors, animals and the dead cannot be considered ethical because consent cannot be given by those involved.

It’s also important to distinguish between desire and behaviour here. Desire is the want or longing for a particular activity and can be kept in fantasy form. Behaviour is acting on one’s desire.

A note on identity and the internet

For some, it is near impossible to find others in offline spaces to discuss their desires with, and this is often due to social stigma or fear of shame. The internet provides the space for one to create an identity that can be anonymous and to make use of that identity to explore online spaces in which one’s desire is discussed. In addition, it can make space for these desires and related identities to be played out safely while also having access to information such as safe sex guidelines for one’s particular expression of desire (Nip 2004).

If one sits in the Judith Butler camp, as I do, then identity is understood as something which is done or performed (Butler 1990). An individual’s understanding of who they are will impact on their behaviour, and they will behave in a way which they deem to be appropriate in terms of the person they consider themselves to be. In the case of marginalised desires, as well as other identities, the internet can be considered a performative space – sometimes the only performative space – to try on one’s identity.

Cover (2012) argues that social networking sites in particular should be considered performative spaces because they provide a platform for one to present one’s identity to the digital community with which one is interacting (2). This is, in particular, associated with the rise in popularity and uptake of social networks such as Facebook and websites such as FetLife where a great deal of time spent on the platform is associated with the maintenance of one’s identity through the upkeep of one’s online profile details and the content with which one interacts. These spaces are useful in that they provide an individual with the opportunity to ‘try on’ an identity in a fairly safe environment (as compared to environments offline).

Creating safe spaces

In creating a safe space, the internet further assists with establishing a sense of belonging for those who may have felt as if they were entirely alone with their particular desire (Mehra et al 2004). An individual is able to find a community of interest and often a community of practice that share one’s need to explore one’s desires. These communities of interest, such as FetLife (within the BDSM community) do not necessarily have specific spaces for exploring one’s desire but allow for one to create a space or discussion and build one’s own community of interest and practice within the broader community.

Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Tumblr and WordPress (to name a few) also provide spaces or platforms for one to seek out, enter or build communities of interest and/or communities of practice. These spaces are made possible by the existence of the internet. However, with these spaces come risks around exposure and use of one’s personal data, mostly due to corporate and government interests.

The internet can form a “(cyber)shelter” for those groups who are unable to maintain physical spaces due to fear of stigma, violence and persecution (Friedman 2007). The internet makes it possible for individuals with a particular desire to seek out those who are similar to themselves or respectful of their right to explore their desire, and to form a community of interest. This provides the space for these individuals to learn from shared experience while granting them anonymity to safely explore their desires (Davis 2010; Hillier and Harrison 2007; Mehra et al 2004).

The ostracisation that marginalised desires face calls for the need of these individuals to gather in digital spaces to strengthen their social identities and this can result in the formation of online communities (Nip 2004: 424). A useful case study that highlights this is the research done by the Brazilian EROTICS research team on Orkut and “Against Inter-Age Prejudice” community (3).

Because of the marginalisation the individuals and groups face offline, it is important that the internet be seen as a safe space for the exploration of desire. However, these individuals and groups are also at risk online because conservative groups may read the content generated by these groups as harmful content.

As APC explains in their description of the EROTICS project, there is a concern that these conservative forces may “encourage new legislation that would treat all online sexual exchanges as sexual predation and all adult content on the internet as pornography”. Doing so would ignore and make invisible the need that many individuals have to access information on their sexuality, sexual health and sexual rights on the internet.

Desire and harm: Spaces to report harm

Individuals who are expressing their identities and related desires online may attract others like themselves into engaging with them online. However, they also place themselves at risk of inviting unwanted attention such as harassment or violence.

Violence that takes place online still constitutes violence. Spaces such as those mentioned e.g. Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Tumblr, WordPress and FetLife ought to make available avenues for reporting and dealing with reports of incidents of violence (harassment, cyber rape, etc), in addition to having policies in place that specifically deal with online violence.

As we continue to integrate and supplement digital/online into our offline lives, we need to be aware of the real digital risks that individuals are exposed to and to treat them with the same weight as we would offline.

Protecting marginalised desires and their communities

The need for protecting the expression of marginalised desires can be divided into two areas:

- The need to protect their right to engage in sharing content and expressing their desires online.

- The need for digital security to protect their data and identities.

There is continued work that must continue to happen which will see the rights of individuals to explore their identities protected from conservative laws that may deem content to be harmful or indecent when content may not be this. Here, again, it is important to distinguish between desire and harm. When the content is not ethical, responsible or consensual, then an argument against the content being available online is valid.

Concluding remarks

In creating spaces online for desires to be explored, expressed, played out and researched, we continue our work of destabilising the gravitational pull to the centre. What do I mean by this? I mean that we continue to move away from prescriptions of what is ‘normal’ desire and pathological desire. We create spaces to explore and shift spaces to allow for the healthy expression of desire, to allow more people ‘hey, I’m not alone’ moments.

And in concluding, the right to express one’s identity needs to continue to be protected while we work to shift the gravitational pull to the centre. As governments and corporations continue to gain an interest in the internet and move to regulate digital environments, sexual rights and internet rights workers need to monitor the changing digital environment and protect it as best as possible from corporate interests and conservative forces.

Appendix

Digital security is necessary for all individuals who make use of the internet and share their data. It is even more vital that individuals who share their desires online protect their data and identities. A few basic tips for protecting ones data and identity online:

1. Create a page on a secure platform, blog or website.

2. Make sure you fully understand the terms and conditions of the digital platform you’re using. Do your homework to ensure you understand the implications of creating and sharing content in the space.

3. Use an anonymous email address preferably from a encrypted source when setting up your account and profile

4. Do not share personal information in the digital space that you would not feel comfortable having traced or appearing in other spaces should your account or the site be hacked.

5. If you share personal information outside of the digital space, make use of an encrypted source such as riseup.net (email) or surespot (chat). Check these sources continuously for whether there have been any changes to their privacy terms. In addition, note that not all communication can be encrypted, for instance, if you are emailing someone from riseup.net address to a Gmail address, the data security of that email is not guaranteed.

6. Report any harassment to the page/site administrators, and continue to push for something to be done.

7. If you experience harassment and violence online, go to Take Back the Tech! and Map It

References:

- Butler, J. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. London: Routledge.

- Cover, R. 2012. “Performing and undoing identity online: Social networking, identity theories and the incompatibility of online profiles and friendship regimes”. In Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies. Vol 18 (2). Pp 177 – 193.

- Davis, T. 2010. “Third spaces or heterotopias? Recreating and negotiating migrant identity using online spaces”. In Sociology. Vol 44 (4). Pp 661 – 677.

- Deacon, D. et al. 1999. Researching Communication. London: Arnold.

- Friedman, E. 2007. “Lesbians in (cyber)space: the politics of the Internet in Latin American on- and off-line communities”. In Media Culture Society. Vol 29 (5). Pp 790 – 811.

- Hillier, L. and Harrison, L. 2007. “Building realities less limited than their own: young people practising same sex attraction on the Internet”. In Sexualities: studies in culture and society. Vol 10 (1). Pp 82 – 100. Sage Publications, London.

- Mehra, B., Merkel, C. and Peterson Bishop, A. 2004. “The Internet for Empowerment of Minority and Marginalized Users”. In New Media & Society. Vol 6 (6). Pp 781 – 802.

- Nip, J. 2004. “The relationship between online and offline communities: The case of the Queer Sisters”. In Media, Culture & Society. Vol 26 (3). Pp 409 – 428.

Image from discussion on marginalised desire and the internet at the Global Meeting on Gender, Sexuality and the Internet in Malaysia, 2014.

(1) An ice cream analogy, but I think it works here.

(2) In digital environments it should perhaps be made known that people are in a constant state of becoming themselves, as is with the case offline. A degree of trust is required when interacting online that individuals are who they say they are and that unless otherwise stated, this should inform one’s interactions with the individual. For instance, someone may identify as transgender and may not yet be ‘passing’ or dressing as their preferred gender. Who they say they are in that moment is what should count because it is that acceptance which may lead them to becoming more comfortable with expressing and ‘performing’ their preferred gender identity.

(3) To read more about this research: http://erotics.apc.org/research/online-sexual-publics-and-debate-interne... or http://www.genderit.org/articles/erotics-brazil-complex-universe-sexuali...

- 18377 views

Add new comment