‘Ever since we started advocating for sexual education stuff… and on our website, I get death threats saying that we are spoiling Indian culture. I keep ignoring, and I wonder if there is a time one should turn around and say something.’

What does it mean to use the internet freely and fully? What freedom do you have to express who you are, how you live your life, what you desire, dream and believe in on the internet? Does your activism shape your experience of being a citizen on the internet? And how safely can you communicate, contribute, exist, navigate and be in the spaces online that can so powerfully connect you to communities and knowledges that build our sense of self?

It is clear that it depends on who you are and if you are “acceptable” to the powers that police and control online spaces. Reading through responses to a survey conducted by the EROTICS project and from my experience in online activism, I was struck by how the ‘norms and values’ of heteronormative, inherently conservative and fundamentalist entities are the benchmarks by which informal and formal control of freedom of expression online are set. Restrictions on the ability to express oneself, gather and contribute online and often violent and vitriolic attacks are experienced by communities and individuals who live and express ‘other’ gender, sexualities or beliefs.

In the first phase of the EROTICS research, it was said that “…the internet has become an important emerging public sphere for democratic deliberations where rights are contested and defended. This is especially so for sections of society who have little access to other kinds of publics due to the multiple forms of exclusion and discrimination they face – based on gender, age, economic status and sexual identity.” While this still holds true, in the past few years, the increase in online violence towards women, sexual minorities, trans activists and others has increased. This vulnerability and the threats made demand that we work to ensure our safety on the internet. Insecurity online is caused by a range of factors, from blocking content on safe sexual health practices, to censoring information on sexual minorities to targeted and frightening attacks towards sexual rights activists. Although blocking of content on sexualities may sound innocuous, it is a frightening practice which compromises access to reliable and life-affirming information, to a sense of self and community.

“When I was studying at the University of Botswana, the varsity censored any information on lesbians, describing it as porn.”

“Using WiFi in hospital accomodation, I was unable to access sex education resources.”

A couple of years ago there were rape threats from a Google group. Every Sunday we were doing street action, and we’d be giving details about where we were meeting. After that, I stopped giving out the details of where we were meeting, and saying that you should email me. Because it’s not just my own safety at risk, but others as well.

The APC internet rights charter says “…the internet and other information and communication technologies (ICTs) can be a powerful tool for social mobilisation and development, resistance to injustices and expression of difference and creativity.” In many instances sexual rights activists are expressing difference or being caste as ‘other’ by conservative groups, governments or individuals. Resistance to this othering often takes creative and innovative responses, including online. Lesbian, gay, transgendered, intersex people have claimed cyberspace as a site of struggle and innovation. However, the increased surveillance, monitoring, trolling and targeted attacks means that the innovation and creativity has to include safety mechanisms, awareness of these threats and the ability to safeguard ourselves and our communities.

Perhaps one of the most important caveats to this is that we are individuals connected to others in online spaces and awareness and practice of our safety means securing our communities. As c5, who trains and capacitates activists in digital security says in all her trainings, “We are as secure as the least secure members of our networks”. Perhaps the mantra we need to chant as online activists working and breathing sexuality rights!

“I run several online discussion groups on Facebook which I moderate. Many threats to harm me physically, etc. Many of these were ideological debates or polemic arguments. Initially I withdrew, but now I am mentally prepared, and I don’t let it affect me anymore. The attacks were extremely personal and disturbing.”

It is not only activists who experience restrictions online. Researchers exploring frontiers of sexual difference and students working on sexuality, find that information on abortion rights, sex worker health issues and breastfeeding to name a few, is difficult to access.

“I am often unable to access my own research pages (which related to pornography and sex work) from places like coffee shops, libraries, etc, where the internet is monitored and censored, but by the private business and not by the government.”

As I said before, my article could not be promoted because it had “Boobs” in the title. Also, once while doing research, I could not go to GoodVibrations.com on public WiFi. It was blocked as pornography. Haha.

How much is our sense of safety constructed through the gaze of others?

Where do we feel safe? How much is our sense of safety constructed and determined through the gaze of others? We often partly measure our sense of self and safety through the gaze of the other. Although as Haraway says “the tradition of reproduction of the self from the reflections of the other” is a construct, we often ‘read’ into the other whether we are safe or unsafe. As we measure and feel safe or unsafe offline, so we have begun to measure our sense of privacy and safety online, as we will explore in this article. Digital safety is critical in an age where surveillance, invasions of online spaces by conservative groups are commonplace. Working in contested areas such as sexuality, the need to understand digital safety and ways of protecting online spaces becomes more vital in our work.

We inhabit the mind, body and spirit which work collectively to intuit things and respond, protecting us and keeping us safe. There are places I won’t go as I feel physically unsafe. But we are not just bodies. We have hearts and minds constructed out of stories with histories, dreams and desires from which we have shaped ourselves and our realities. We are connected to communities, families and networks who also have stories which have formed our understandings of safety. We are constructed beings offline as we are constructed beings online.

Sometimes ‘the gaze’ of the other online is as dangerous and life-threatening as it is offline.

“I gave my number out when I got into films. One of the calls was from some guy who started asking what’s your rate, what’s your price. You’re a transgender, you’re an actress, you must be a prostitute. You must be having a rate.

Another was trying to find out where I live. He found me first on Orkut and Facebook, and was then trying to find my number. [Using these social media platforms] to find information. He went to a shop I go to and tried to get my number from there. He was actually living in the next street – I could see his house from my window – and I found out he was standing there looking at me from my window. And this room, it was also my dressing room. And then I found out he was doing that. A couple of weeks later, I was home coming late from an event, and I was walking on the street and he suddenly appeared with a few friends and was drunk, and he caught my hand, and he was like you’re beautiful, and your transgender and all of you like boys, why don’t you look at me’.

Another guy – from Facebook he found my work place, got that phone number, and then from that, found my mobile number.”

The fluidity between our offline and online experiences is such that they make seamless transitions and blur any boundary between the two. Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto speaks to belief that there is no distinction between natural life and artificial man-made machines. What we share and do online has implications offline. Just as we secure ourselves and our communities offline, so we need to reflect, learn and implement measures to ensure our safety on the internet, in social media spaces and in our email writing.

When activists’ experiences of safety and their freedom to express themselves fully online are trivialized by those who should be allies, there is a frightening dis-juncture between allies and enemies in the online Freedom of Expression movement. When individuals target women because they are women, these violations of freedom of expression and the safety of women are often trivialized by other FOE allies. It seems that is often difficult for people to take seriously the “zillion little brothers” that daily perpetrate sexualized attacks on women usually through social media. The recent #FBRape campaign highlighted the many ways that women are persecuted and brutalised through one of the largest social media platforms, Facebook. However, some FOE ‘allies’ seem to reduce these attacks to insignificance, partly cause they are mostly acts of individuals rather than States or corporations.

Being safe online is not only about protecting ourselves against governments and corporates but we need to secure our activism and identities from individual users, who mainly use social media as the main for attacks.

What are the safety issues experienced by sexual rights activists?

Censorship through blocking of content by governments, Internet Service Providers (ISPs), universities and institutions is commonplace. Here are just a few experiences:

“My online ad looking for women who had underground abortions was deleted from one service.”

“We can’t watch LGBT movies online. I don’t mean porn. We can watch porn.”

“In my work at the university, some websites have been blocked. even though their content is not pornographic. I think they just pick up certain words and black list the sites. Government using ISP blocking sites suspected with immoral contents, i.e porn sites and adult chat rooms. This policy also affect some sites with no obscene content at all.“

The skewed responses to content on sexuality is reflected in these experiences. Critical information on sexual health issues is blocked or crudely filtered, reflecting a conservative and misogynistic mindset. While information on sexuality is filtered, as one responded in the survey say “sexist content is rife and without restriction.”

Monitoring is another way in which we can be vulnerable in online spaces. The internet is a threat to many governments as people are able to express, act, plan and resist. Regulation is commonplace and activists working for a free and open internet are acutely aware of how freedom of expression and association is being challenged. Those that do are often carefully monitored and extreme cases arrested. As on respondent said

“(I was) vilified on a pro-government website for my work on freedom of expression.”

Another experience was shared:

“Sometime freedom of speech can’t really obtain in a very restricted nation, I face some difficulties when wanted to express views on religion, races or even government….”

Re-victimisation of survivors of sexual violence who choose to fight back and challenge the violence via social media is serious and extremely common. Vicious tactics, usually by individuals, can effectively silence survivors or sexual rights activists who have chosen to speak out and fight for their right to expression online as survivors and/or sexual rights activists. Re-victimisation can be devastating and taking steps to safeguard oneself online becomes critical in such situations.

Social media can be points of vulnerability for activists

The use of social media such as Twitter, Facebook and blogs as well as YouTube has increased substantially in activist circles. Many respondents identified social media as points of vulnerability as activists are stalked, sent threatening messages or their mobile phone numbers were culled from their profiles. Pictures are downloaded, manipulated and forwarded in unpleasant and degrading ways which impacts on the reputation of people and can be personally devastating. People are re-victimised when they challenge their online abusers or people thoughtlessly forward images of abuse. This kind of attack is particularly vicious as it re-engages the trauma. Awareness of what is shared via social media is important for sexual rights activists who are more harassed and threatened than others.

Someone took X’s Facebook profile picture and created a fake Facebook profile. This person, posing as X, begged a man to go out with her. And then screenshots of this [the false flirtatious messages] were put on Orkut.

In addition victims of sexual harassment or rape are often revictimized by the posting of pictures or videos of the incident online or by further online harassment:

‘I faced sexual harassment and it was published in the Sunday Guardian, and then it was put up on the Internet. But the kinds of comments that went around Facebook – all kinds of judgements passed upon me. Like, how can it happen to a man? This person will never do it. Kind of character assassination that takes place. My number was there and people began to call, and they called my parents, and then my parents didn’t know what was going on. That was also the time I came out to them. Questions from relatives like ‘Is he really a man? Do you need to take him to a doctor?’ they started passing comments to my brother in his college as well. Finally that person did come out and did give a public apology.

How can we be safe?

As The Lorax say in the Dr Seuss film “Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, Nothing is going to get better. It’s not.”

The old saying that “knowledge is power” is important and true. The internet is unsafe and we need to inform and skill ourselves and our communities to be safe. Self-defence online! Given the particular threats faced by sexual rights activists online and women in particular, here are some tools, strategies and resources for your online safety.

I am reminded of a slogan that is used in many struggles: “an injury to one is an injury to all”. Being personally safe will help your community be safe. This is perhaps one of the most important things to remember with online safety. Don’t compromise others through your lack of security. If you are part of an organisation or network, discuss issues of digital safety, create a policy for all members to adhere to.

– Know how the internet works. This enables you to see where the potential threats come from.

– Keep your computer healthy. Condomise! Ensure that you regularly update your anti-virus package as viruses are dangerous and can contain spyware.

– Protect the data on your computer. Password protect your computer and encrypt sensitive data. Securely delete old files using Ccleaner.

– Search the internet securely using https everywhere and regularly clear your browsing history.

– There are many ways that people can gain access to our private accounts that never entail actual hacking, but one of the most common is our own poor password management. Find out what the risks are, and how to build better passwords and practice.

– Mobile phones are ubiquitous and used by many activists to connect, communicate and to mobilise. They can also be used to track and monitor someone’s location or private communication. Learn how to better protect your privacy on mobile phones.

– Social media platforms can create vulnerabilities that we need to guard against. Make sure that you read the privacy statements of platforms such as Facebook and twitter. Do not upload compromising photos and never upload or tag people without their permission. Keep your passwords or passphrases safe, change them regularly and remember to logout once you have finished.

-Be safe by reading more about online safety!

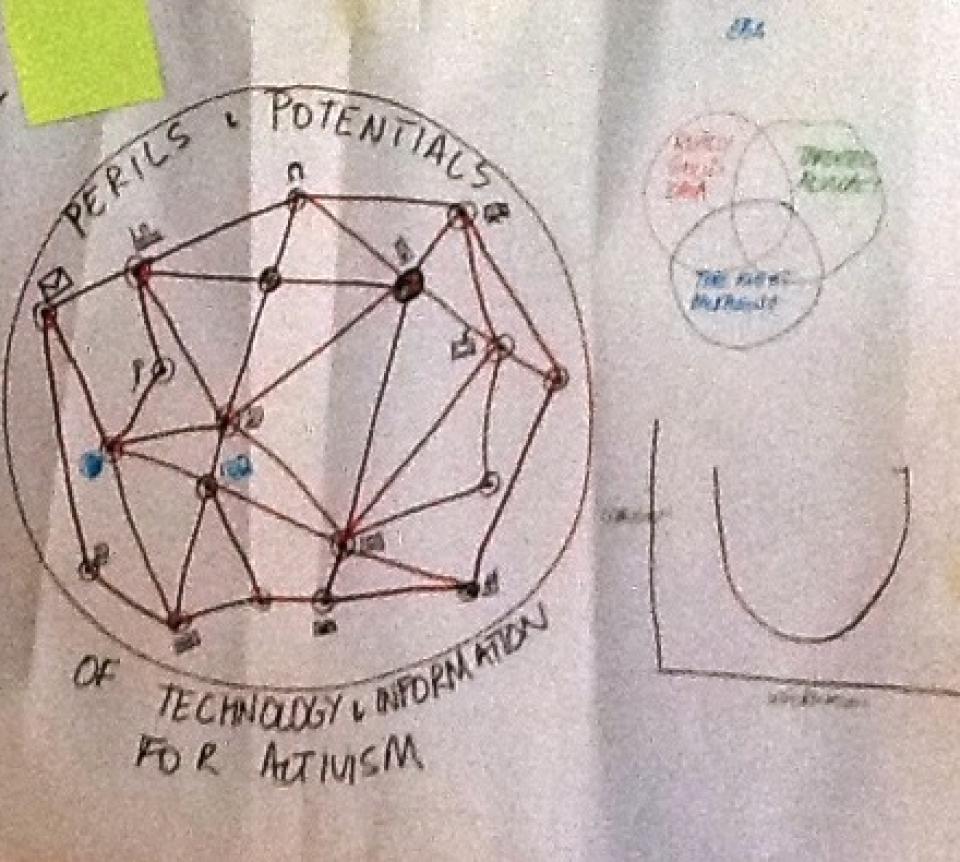

Image taken during the APC EROTICS workshop in India, by CT from APC.

—-end—-

- 24029 views

Add new comment