Here we go again. On June 13, the Indian government blocked 39 websites which allow users to share porn, among other content1. I’m not anti porn, but even if I were, this wouldn’t make much sense to me. Internet users can easily watch or share porn on a zillion other websites, so what can such a random action possibly achieve? And it is random; we have no idea why those particular sites were chosen. Is it because they contain child porn, which is illegal to watch? We don’t know. Is it because someone complained? If so, about what? We don’t know. Is it because these sites contain something that could cause harm? If so, what harm? Don’t know. No one’s saying anything.

This news item resonated more strongly as I mulled over the APC EROTICS’s Global Monitoring survey which was carried out for the first time in India this year. Exploring how sexuality rights activists use the internet in their work, the survey includes questions on censoring, monitoring, blocking and filtering of online content on sex and sexuality.

Of the 19 activists who responded to the survey in India, most said that the Indian government is more likely to restrict online content that is ‘political’ than content that is ‘sexual’ – and is most likely to clamp down on any content that can be labelled ‘anti-national’ or ‘anti-government’. True. Of late, the Indian state has been particularly sensitive. Most recent example: In 2012, political cartoonist Aseem Trivedi’s website, Cartoons Against Corruption, was blocked, while he was accused of sedition and sent to jail2.

The trend to restrict online political content is particularly evident in Kashmir, where a decades-old political conflict has now become a part of everyday life. In 2009, post-paid texting on cellphones was banned for a few days. In 2010, Facebook administrators were arrested to prevent information exchange and mobilization via social media during a five-day curfew following street protests3. In 2012, internet and cellphone services were suspended for a day, after a YouTube video criticizing certain Islamic practices was uploaded4.

So far, there have been fewer instances when the Indian government has blocked sexual content. Best known case: the 2009 blocking of savitabhabhi.com5. The site charted – again in animated form – the sexual escapades of the sari-clad Savita Bhabhi, whose unbridled desires turned on men and women viewers. Heaven knows how this could ever pose any form of danger, since it was all consensual sex. I can only posit that the notion of female sexual desire is so alien to policymakers that they could not handle this being represented, even in cartoon form. Solution: turn off access. Turn off the site. Another random action that made no sense.

Going back to the survey, sexual rights activists said that child pornography, content containing words such as ‘sex’, ‘breast’ or ‘penis’, and ‘obscene content’ including porn and sexual images are most likely to be regulated from the vast spectrum of sexual content online. Least likely to be regulated: content around contraception, abortion. Somewhere in between: LGBTI content. Most agreed that the government usually cites ‘anti-terrorist measures and security’ as the main reason for regulation (which goes hand in hand with regulating political content), while the next given reason is ‘public decency and upholding morals’. Respondents also said that the Indian government is less likely to give the following reasons for regulating online content: maintaining law and order, preventing blasphemy, religious insult or slander, protecting culture, tradition, women or children.

Internet rights activists in India have long bemoaned the lack of transparency in regulating the net – respondents agreed with this. Most said that while we do have specific laws around this, it’s not clear what constitutes ‘unlawful content’ in India, what legal and judicial processes exist to report cyber-harassment, and on what basis filters and blocks are carried out. Respondents ranked the government as the biggest internet regulator or policymaker, followed by popular social networking service companies such as Google, Facebook and Twitter, followed by internet service providers. In the absence of more details, I couldn’t figure out why social networking companies were seen as key policymakers in the larger internet space: is it because of their size? Their scale? Because they are so widely used both for activism and personally? Because they allow users to regulate ‘offensive’ or ‘harmful’ content? Are they seen to have more influence on policy than they actually do? This needs further consideration.

When it comes to actually using the internet, most sexual rights activists said their work would either be impossible or difficult to do without the internet, and that they consider the internet “an important public sphere for advancing sexual rights”. This gives me inordinate joy – and hope, since there’s often a strange sleight of mind around online activism. On the one hand, the net is now as ubiquitous in our changemaking spaces as a cup of chai (tea), and has gradually become part of activism’s essential toolkit, even in a country where stable electricity is not a given. On the other, online activism – and activists – are still viewed with skepticism and suspicion, held in disregard, and seen as less legitimate than their offline counterparts.

This puritanical and hierarchical thinking drives me almost insane, given that ‘purity’ and ‘hierarchy’ are exactly what we are trying to dismantle through our activism. Right? Purities of caste, gender, and sexuality which lock us into boxes in which we don’t belong. Which look at and label us from the outside, in ways that don’t make sense when looked at, inside out, from the lives we live. Hierarchies that place other needs, such as economic ones, above our other needs as women or as sexual beings. Aren’t we struggling to bring about a world in which a woman’s right to be free of violence or to choose her lover or sexual partner – of any gender – is as important as her need to earn enough? In other words, aren’t we trying to shift our thinking away from the ‘pure’ and the ‘hierarchical’? And if so, why not dismantle these in our thinking around activism too?

Small subversions can seem like giant steps in these twisted landscapes. Most respondents to this survey said they had participated in both online and offline campaigns, hurrah! Their biggest concerns related to privacy and some aspects of security, concerns that private information could be accessed without their knowledge, and that viruses, etc could cause technical damage. About 40% of respondents had faced sexual, offensive, racist and other violent threats and comments online – and about 40% had experienced a lack of support from others in responding to these (although these could be different from the previous 40%). How did they deal with such problems? No clear pattern here. Some said they got technical help from others, reported it, stopped what they were trying to do, etc. Others said they ignored this, toned down or kept doing what they did. “I don’t give a damn,” said one activist. None said they had moved offline as a result of such challenges, which deserves another hurrah.

Most sexuality rights activists said they use the net either to find information that can’t be found offline, to share information quickly and widely, or to network in relatively safer conditions than face-to-face. In terms of the kind of information, 74% look for official documents online; next in line – at 68% – is information on various kinds of sexual violence. About 57% said they surf for research on sexuality, information related to LGBTIQ, stuff on other marginal groups, communities and sexual practices, sex education, pre-marital sex, pregnancy, abortion, contraception, HIV/AIDS, STIs. And about 40% of participants said they look for information on sex work – or for stuff they could use personally or socially: dating sites, porn, soft porn, erotica, escort services and chatrooms.

Looking for – and sharing – information may seem a tepid form of activism compared to burning up the streets. But let’s not forget that information has been at the heart of some of the most radical campaigns for social justice, including in India. Think RTI, or Right To Information, an Act that emerged in India from the most humble of beginnings: on discovering that daily-wage construction workers were being paid less than their due under the Minimum Wages Act, activists accessed government data showing that contractors were recording ‘full wages’ against each name, claiming this from the State, pocketing a part and paying out less.

Where sexuality is concerned, accessing and sharing information is about as radical an act as any. Think of how starved of information we’ve always been in India around sex and sexuality; no, those classes where they shamefacedly taught us about the reproductive system (without referring to sex) and about menstrual hygiene don’t really count as adequate information. And that’s just some of the urban privileged. What about the rest? Information around sexuality has always been restricted in India in various ways – ‘blocked’ by parents, ‘regulated’ by politicians who don’t believe that sex education should reach schools, ‘filtered’ by a society which selectively provides only those nuggets of information that uphold societal norms, and ‘monitored’ in various ways. Think how in the era of less information or greater silence, homosexual acts were considered ‘against the order of nature’. Think how the reading down of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code originated from a citizen’s report documenting problems with this section6. This provided the underlying information needed to start challenging this provision.

All over the world, the internet has been a huge channel for accessing information that is at the heart of sexual rights. So many examples, specially around silenced sexualities. In Lebanon, the establishment of the gaylebanon.com website has become an important moment in LGBTQI organizing. In South Africa, trans individuals get information on sex-reassignment surgery from the net, including risks and experiences of others who’d gone through this. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, activists mobilized largely on the net to challenge a bill against homophobia – that was the only safe space7. And in India, where schools in many states are not allowed to provide sex education, where do many students turn? To the net, of course. And where do folks, at least those who are connected, go to find sex, intimacy or relationships? To the net, of course.

Four years back, an EROTICS study recorded how women in India use the net in various ways to express and explore their sexualities from putting up ‘sexy’ pictures to flirting with strangers. The cloak of anonymity that the net provides is vital to enabling these experiments and encounters – in this context, 74% of the respondents to this survey agreed that anonymity is a critical component of online safety. At the same time, very few (less than one out of five) felt that sexual rights advocates take online security issues seriously in India or include online threats and risks in their overall security assessment.

Although users and activists in India use both online and offline spaces, ‘sexual rights’ and ‘internet rights’ remain separate domains. So while activists may use the net to store personal information, many do not do this in a way that keeps private information private. While a sexual rights activist may get much of his or her information from the internet, he or she may not participate in anti-censorship efforts to keep this flow of information free and open. And while the online world provides much more space for sexual speech than the offline world, few sexual rights activists will think of protecting online free speech, including sexual speech, as part of their mandate.

Conversely, internet rights activists who fight for free speech online do not think of sexual rights activists as their allies. The two worlds are still too separate for these to mix. Internet rights activists fighting to reduce online harm, violence and abuse rarely think of gender rights activists who do the same offline as ‘natural allies’. Anti-censorship activists rarely think of civil liberties groups or documentary filmmakers who fight offline censorship as their counterparts. Those working to protect sexual speech – including pornography – rarely rely on the nuanced understandings that sexual rights activists have developed on this issue. Let’s not forget that porn has been around forever (the first attempt to ban it was recorded in Rome in the 1500s) and that the biggest ‘porn wars’ have been fought offline8.

On a site recently, I read the term ON = OFF, shorthand for online = offline. It struck me as prophetic, a formula for the way we live now, not just in our personal domains, but also in our activist spaces. ‘On’ and ‘off’ are no longer binaries or opposed actions, like flipping on and off a light; today, they’re as tightly tangled as a ball of two-skeined wool. We flow among them effortlessly, sometimes more on than off, sometimes more off than on. Pulling them apart seems pointless. Placing one above the other seems woolly. It’s like women’s rights’ and ‘human rights’. Yes, there was a time when these two didn’t go hand in hand, but is that the way we see them now? Nope. Not to stretch the analogy to breaking point, but if there is a time and space when we need to bring these other seemingly disparate skeins together – the sexual and the internet – it is now.

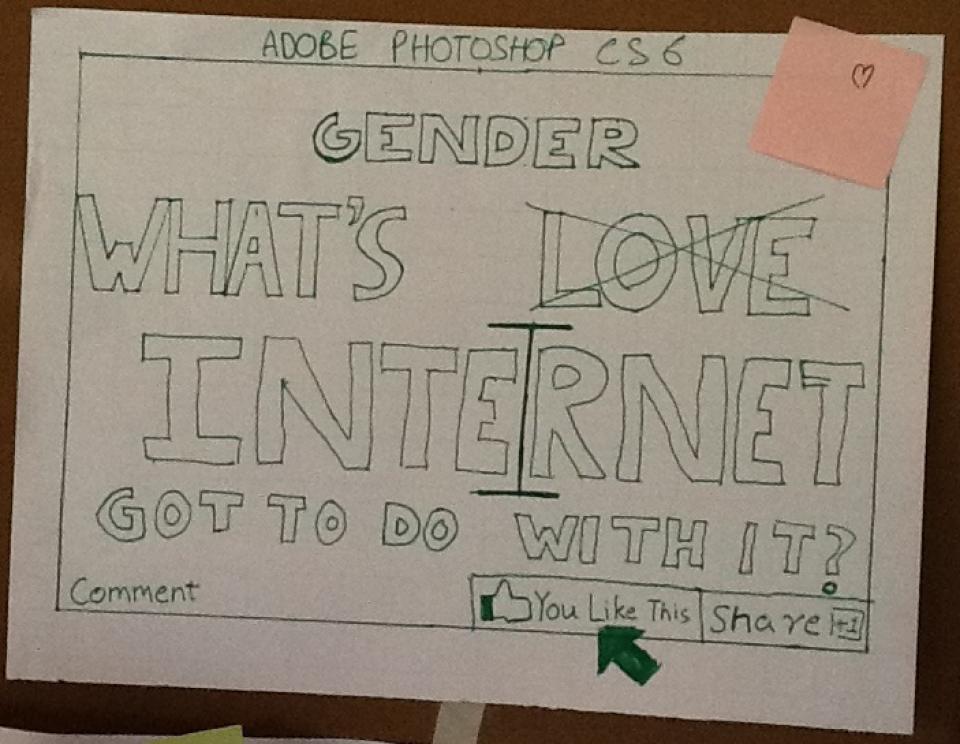

Image taken during the APC EROTICS workshop in India, by CT from the APC.

—-end—-

More about the author:

Bishakha writes non-fiction, makes documentary films and runs Point of View, a non-profit that amplifies the voices of those silenced due to their gender or sexuality. She has edited Nine Degrees of Justice: New Perspectives on Violence Against Women in India (Zubaan, 2010) and And Who Will Make The Chapatis? (Stree, 1996). Films she’s directed include In The Flesh: Three Lives in Prostitution and Taza Khabar: Hot Off The Press. She is on the boards of non-profits including Breakthrough, CREA, Dreamcatchers, Majlis, and the Wikimedia Foundation.

Footnotes:

1 http://www.hindustantoday.com/2013/06/27/indian-govt-has-banned-39-porno…

2 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aseem_Trivedi

3 http://www.kashmirtimes.com/newsdet.aspx?

4 http://www.hindustantimes.com/India-news/Srinagar/Kashmir-govt-not-banni…

5 http://www.dnaindia.com/speakup/1269904/report-what-has-savita-bhabhi-do…

6 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Section_377_of_the_Indian_Penal_Code#Legal_…

7 http://www.giswatch.org/en/freedom-association/sexuality-and-women-s-rights

- 23735 views

Add new comment