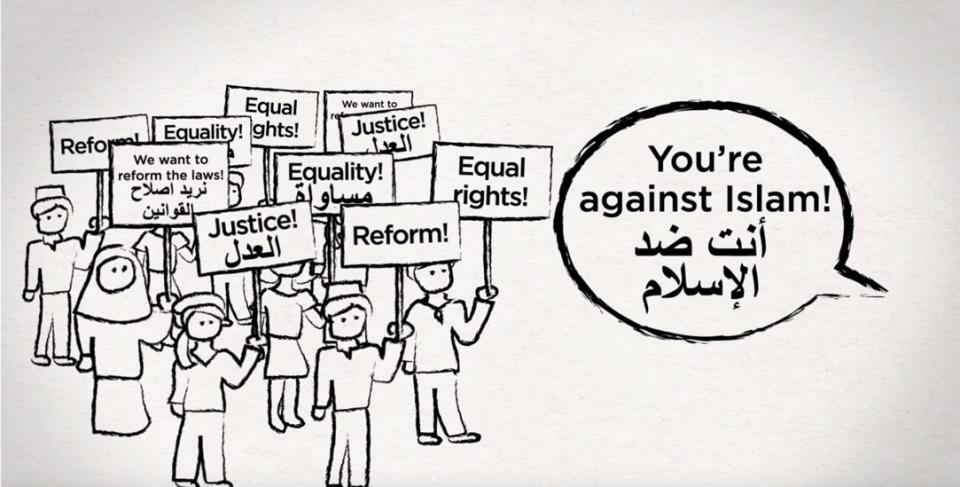

Image description: Illustration of protesters faced with speech bubble with text in English and Arabic saying - "You're against Islam". Source: Video by Musawah titled Shari’ah, Fiqh and State Laws (English, with Arabic subtitles)

In July 2014, a fatwa1 was issued by the religious authorities in the state of Selangor, among others, declaring Sisters In Islam (“SIS”), a non-profit women’s rights organisation in Malaysia as an organisation that practices liberal ideas and religious pluralism and therefore a deviant organisation. The fatwa further declares that any publications by SIS must be banned and directs the federal agency, Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (“MCMC”) to block any social media sites that contravene Islamic teachings and Syariah principles.

SIS has since challenged the legitimacy of the fatwa by way of judicial review in court. After a lengthy and exhaustive legal proceeding, on 27th August 2019, the High Court of Malaya held that the fatwa still stands and that the High Court does not have the jurisdiction to determine the legitimacy of the fatwa.2

SIS has been an instrumental actor in amplifying the voices of Muslim women to public, decision makers and legislators across various issue i.e. gender-based violence, child marriage, female genital mutilation (FGM), gender equality in Muslim marriages and Islamic Family Laws.

SIS has been an instrumental actor in amplifying the voices of Muslim women to public, decision makers and legislators across various issue i.e. gender-based violence, child marriage, female genital mutilation (FGM), gender equality in Muslim marriages and Islamic Family Laws. The Telenisa service from SIS – a free legal helpline has helped over 10,000 women and men for Islamic Family and Syariah Laws in the country.3

SIS has maintained that the state religious authority has no power to administer or to regulate affairs of the organisation, as it is an organisation registered and incorporated under the federal law. The fatwa is a blatant and gross violation of SIS’s right to freedom of expression as guaranteed under international human rights laws and the Federal Constitution. The religious authority had gone over and beyond their executive power in declaring SIS deviant and in seeking to direct MCMC to block social websites that contravene Islamic teachings and Syariah principles. Legally speaking, the fatwa is obviously unconstitutional and could not hold before the very fundamental principle of rule of law. In a democratic country like Malaysia, law-making process cannot be delegated or exercised by an exclusive group of people that are not democratically elected and certainly not by those who do not uphold people’s right to freedom of expression or right to debate matters of religion.

Heartbreakingly, the extent of control and power the religious authority has over SIS is not a mere legal one. The struggle of SIS must be contextualised against the politicisation of Islam, Malay nationalism and Malaysian pluralism in this country. In Malaysia, legislative authority lies with the federal government, but each of the thirteen states has the authority to legislate on various matters as provided by the Federal Constitution. One such matter that falls within the purview of state authority is related to Islamic law. Since independence, the dominant political party has capitalised on Malay special privileges and the Islamisation of bureaucracy and public life as a weapon to secure support from the Malay Muslim constituency, which comprises more than 60% of the total electors in Malaysia. One such strategy was the institutionalisation of Islam within laws and policy and the promise of an Islamic state to enhance their own political legitimacy. Under such pretext, Muslim womanhood and family have become the locus around which efforts have been made to re-create moral values and defend Islamic authenticity (Zainah Anwar, 2001).

Fatwa has long been weaponised to control women’s voices, bodily autonomy and freedom. In a CEDAW Shadow Report submitted by Malaysia’s civil society in 2018, it is reported a series of fatwas limited the rights of women to bodily integrity, among others:-

-

a fatwa making it obligatory for girls to undergo circumcision;

-

a fatwa against pengkids (a Malay term referring to a person born female whose gender identity and gender expression are androgynous or masculine);

-

a fatwa against women who shave their heads; and

-

A fatwa against gender-confirmation surgery (Any male or female who has undergone gender-confirmation surgery will remain the sex that they were at birth according to this fatwa, though an exception was made for people born intersex (the most “functional” organs should be kept)

Even though a fatwa has no legal enforcement until they are adopted into law by the individual states of Malaysia. However, the prevailing sentiments and cultural norms behind the fatwa do raise significant concerns. A woman was banned from emceeing in the state of Kelantan by the local authority due to a purported fatwa declaring women’s voice as aurat4 and therefore is banned from being heard in public space. It was only later clarified by the state Mufti that “Women are not barred from speaking up or using the microphone at events as their voice is only considered as a form of aurat when performing prayers” – which is equally discriminatory.5 Even in the absence of a written fatwa, the obscure understanding of Islam has legitimised and normalised a regressive regulation over women’s voices and visibility in public space.

Muslim women are expected to be docile, discreet and to uphold the sanctity of Islam, whereas the production of Malay Muslim masculinity relies on men being racially and religiously superior (Basarudin, 2016, 67). Presence of Muslim women at the women’s march in Malaysia, especially when seen donning the hijab often received disproportionate attacks on social media and blogs. They are targeted for bringing shame to the religion or that they are incapable of thinking and exercising agency over their mind because they have been corrupted by the liberal agenda and feminism (EMPOWER, 2018, 32-38).

Presence of Muslim women at the women’s march in Malaysia, especially when seen donning the hijab often received disproportionate attacks on social media and blogs.

There is a belief among those in religious authority that matters of religion should not be debated in the Parliament by elected representatives who are not Muslim and by those who lead less than pious lives – and certainly not by non-Muslim (Zainah Anwar, 2001, 247). This ethnoreligious complexity has pitched Malaysians against an unproductive binary of Muslims and non-Muslim, rendering it hard for non-Muslims to speak up against any violation of human rights. For instance, two non-Muslim women were attacked on Facebook for speaking at the launch of an online quiz series called Hidayah Muslimah (enlightenment of Muslim Women). The attack focused on their race and attire, that they do not "cover up" themselves.6

The fatwa and the decision of the High Court to uphold the fatwa is not just an attack against SIS, but a persistent and systemic attempt by Islamist groups to control and silence all those who challenge the mainstream orthodox views. It is a disheartening development for many of us who had hoped that the change of regime during the last general election would ensue true progress for gender equality. Even with the fatwa hanging over their heads, SIS vows to continue championing the rights of women in Malaysia,7 and so do many of us who demand gender equality and meaningful freedom of expression in Malaysia.

Footnotes

1 A fatwa is not legally binding but is theological and legal reasonings given by a mufti to enlighten and educate public about Islam. It is opinions of the religious learned within a particular social context to help Muslims lead a life according to the teachings of Islam. See: https://www.thestar.com.my/opinion/columnists/sharing-the-nation/2017/0…

4 Intimate parts that needed to be covered up in public space

6 As documented in Preventing Violent Extremism Online: Understanding the Phenomena through a gender lens, page 19, https://empowermalaysia.org/isi/uploads/2018/10/Preventing-Violent-Extr…

7 https://www.malaymail.com/news/what-you-think/2019/08/27/a-dark-day-for…

Additional References

Azza Basarudin “Islam, the State, and Gender: The Malaysian Experiment” in Humanizing the Sacred. (USA: University of Washington Press, 2016), 39-72

EMPOWER. Preventing Violent Extremism Online: Understanding the Phenomena through agender lens. (Malaysia, 2018). See: https://empowermalaysia.org/isi/uploads/2018/10/Preventing-Violent-Extremism_Final_Print_single.pdf

Women’s Aid Organisation and others. The Status of Women’s Human Rights: 24 Years of CEDAW in Malaysia. (Malaysia, 2018) See: https://wao.org.my/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/The-Status-of-Womens-Human-Rights-24-Years-of-CEDAW-in-Malaysia.pdf

Zainah Anwar “What Islam, Whose Islam?: Sisters in Islam and the Struggle for Women's Rights” in The Politics of Multiculturalism: Pluralism and Citizenship in Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia, ed. Robert W. Hefner. (Honolulu, USA: University of Hawaii Press, 2001), 227-252

- 15511 views

Add new comment