While the internet empowers women living with HIV/AIDS by providing information about their right to privacy, internet rights in Indonesia are being threatened by government practices of blocking and filtering content. During the last Internet Governance Forum that took place in October 2013 in Bali, APC talked to Indonesian activist Kamilia Manaf about the challenges that sexual rights and internet rights are facing in the country, as well as the impact that an international event like the IGF has in their advocacy work.

Analía Lavin: What’s your experience as a local activist participating in the Internet Governance Forum?

Kamilia Manaf: The IGF is a great opportunity for us, a community of women from Indonesia, to talk about the internet, women’s rights and LGBT rights. When we want to talk about internet rights, a lot of people compare the issue with health or with economic rights, and by saying that they are more important we can’t have a real discussion. Here, with the support of international networks like APC and other organisations active in LGBT rights, as well as local NGOs, we are able to engage in collective discussions. We also have the support of the National Commission of Human Rights, and as a result we can be more confident about giving voice to our rights and our discourses. And the fact that it’s happening in Indonesia allowed us to bring more women with their local perspective, who afterwards will be able to speak about IT and internet governance in other spaces.

AL: Does participating in a global space like the IGF have an impact in your local advocacy?

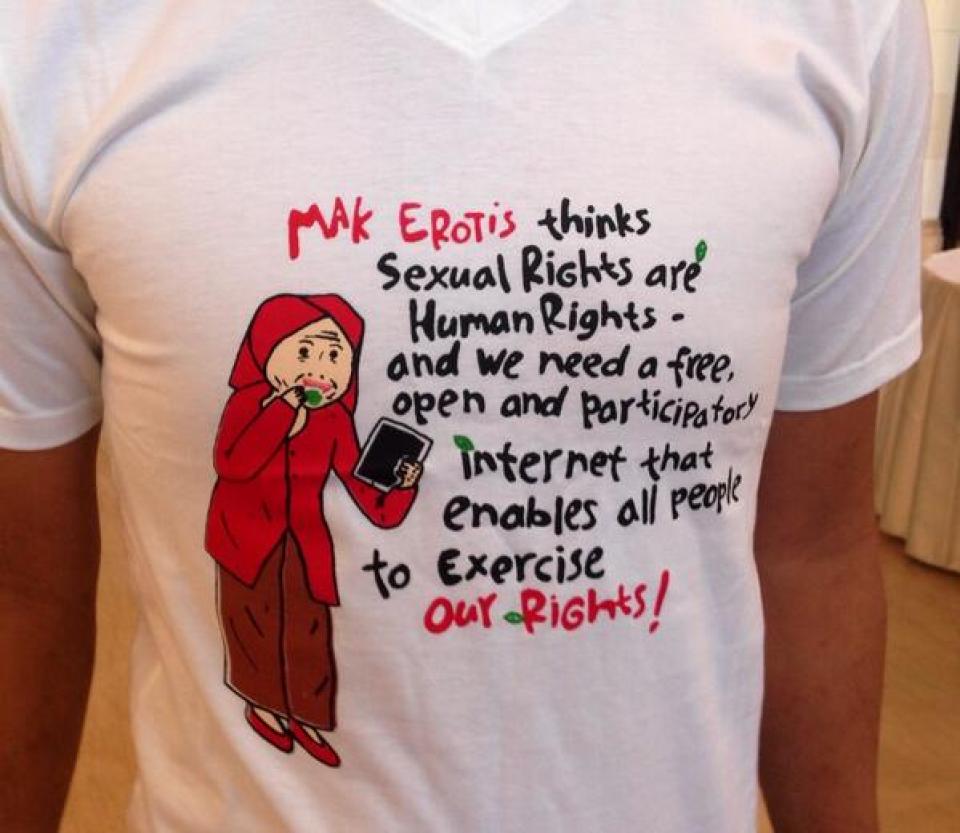

KM: Yes, that’s why we came prepared. We came here with information about our demands and our perspectives, with brochures and posters and any medium that allows us to speak. We try to be in as many sessions as possible, to meet all the people we can, and we try to reach the people that we don’t meet through these materials. We’re already seeing the results, since one of the Indonesian mainstream media has published what we are doing here about LGBT rights. The IGF is the centre of attention for internet governance, so it’s a very strategic space from which to speak.

This is also good for minorities, like women who are living with HIV/AIDS and lesbians, who are here and are empowered by having a safe space to talk, to voice their rights in a confident way. The beauty of IGF is that it’s not an NGO-only space: it’s a space to collaborate and engage, to understand each other, between people from different spaces. We’ve had interesting conversations with both the government and the private sector.

AL: Your experience is then different from that of people from Azerbaijan at the IGF last year, when the government was really pushing against them.

KM: Yes, but we cannot guarantee that this will continue after this IGF. We don’t know yet what the impact will be for us. Here, right now, we’re having a positive impact. I just had a meeting with an Indonesian ISP association in Bali to talk about gender and discuss our criticism of their Miss Internet Bali initiative at IGF 2013. We noted how the initiative puts women in the domestic sphere, where the struggle of women’s rights activists are supporting the women leadership and political participation on internet governance. The meeting was also attended and supported by APC, and this was a very rare opportunity for us.

AL: In your experience, what’s the connection between the internet and women’s rights?

KM: It is very connected, of course. As part of a minority group of young lesbians, we need the internet to organise our community, since we don’t exist in a physical space. The internet and mobile phones have allowed us to go from an informal community of people hanging out, to a formal organisation. It’s a very political space for sexual and LGBT rights activism. Activists read articles and comment on them, and by doing that they strengthen their community. Something similar happens with women living with HIV/AIDS: they’re not confident, but if the internet is providing sufficient information for them, they learn that they can have privacy when they access information, that they can be anonymous. The internet really provides a space for sexual rights community activism.

The challenge now is that we are facing blocking, filtering, censorship, cyber homophobia, online harassment and hate speech. The internetis an extension of real life: whenever we face discrimination and violence in physical, offline spaces, it continues in online spaces. We are already discriminated against and we have a very limited space offline, and now they want to limit our space online too. So it’s about space actually, where we want to do our politics.

AL: The Indonesia government is currently using the concept of ‘decency’ to filter content. How does it work?

KM: This is how “decency” works for them: if you know someone from Facebook and you are raped, and it’s your fault, because you weren’t careful enough, and you didn’t behave yourself. They’re not educating the men who rape, or their sons. Their main message seems to be: “Women should behave while using social media”. They are also using decency as an excuse to block websites. The government publishes a list of websites they consider pornographic or malicious which are then blocked, but there is no discussion with people about why they block them and how society can challenge that list. For example, if my website is blocked because they consider it to be pornographic, there is no mechanism, procedure or information for you to say, for example, that your website is about education or rights.

Sometimes when we contact ISPs they say: “Oh, it’s a recommendation from the Ministry,” then we mention it to the Ministry and they say, “Oh, we never said anything to the ISP.” What we demand is transparency and accountability about the process and about how government is working with the private sector to manage the filtering and blocking. We also demand civil society participation, and the inclusion of women groups as part of civil society.

- 7003 views

Add new comment