This article is based on the speech given by Bishakha Datta at the Disco-Tech event organised by APC that took place at the 2014 Internet Governance Forum in Turkey.

Five snippets from three months.

In August, Indian actress Poonam Pandey dons a bikini for the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge and posts a video of it on Facebook. Facebook’s reaction? Ban the page, which is followed by 2.1 million people.

Why? We don’t know.

In July, American teenager Samantha Newman instagrams photos of herself in her bra and undies, like many other teens. Instagram’s reaction? Take down her page, not that of the other teens in inner wear.

Why? She’s too fat.

“Fat is not a bad word,” says Samantha Newman, who gets her pic back online after a hue and cry. “How confident can you be if you keep censoring yourself because people don’t want to look at you?”

Another Instagram moment. Scout LaRue Willis posts a photo of herself “in a sheer top and a post of a jacket I made featuring a picture of two close friends topless.” Guess what happens? She gets kicked off Instagram and the platform deletes her account.

Why? Nipples aren’t kosher on social media. (But non-nippling nudity is.)

LaRue Wills organizes a #FreeTheNipple protest in New York City, a physical one with magnificent masked topless women roaming the streets, and explains online that “her situation was in no way unique. Women are regularly kicked off Instagram for posting photos with any portion of the areola exposed, while photos sans nipple – degrading as they might be – remain unchallenged.”

Now West Coast US. After porn performer Eden Alexander goes into a coma from an untreated skin infection, friends plan to crowd-fund her treatment on WePay.

What does WePay do? Cancel the campaign and say it will send money back to donors.

Why? ‘Cause she’s a porn performer. WePay’s assumption: must be raising porn money.

“This wasn’t money that was going to be used to make porn.” say outraged friends. “It was money that was going to be used to keep one woman and her two small dogs alive.” After a hue and cry WePay relents and offers to support a new campaign, she raises $10,000 and this one has a happy ending.

But Happy Play Time doesn’t. Designer and developer Tina Gong creates this iOS game to remove the stigma around female masturbation. Its protagonist: a female vulva called Happy that’s anthropomorphic and not that explicit. Apple’s reaction? Reject it for “excessively objectionable or crude content” and “containing pornographic material.” So Happy Play Time won’t be included as an iTunes App.

Buoyed and bolstered by sympathizers, Tina appeals to Apple’s App Review Board. The result: not happy. Not happening.

So what’s going on? Five things.

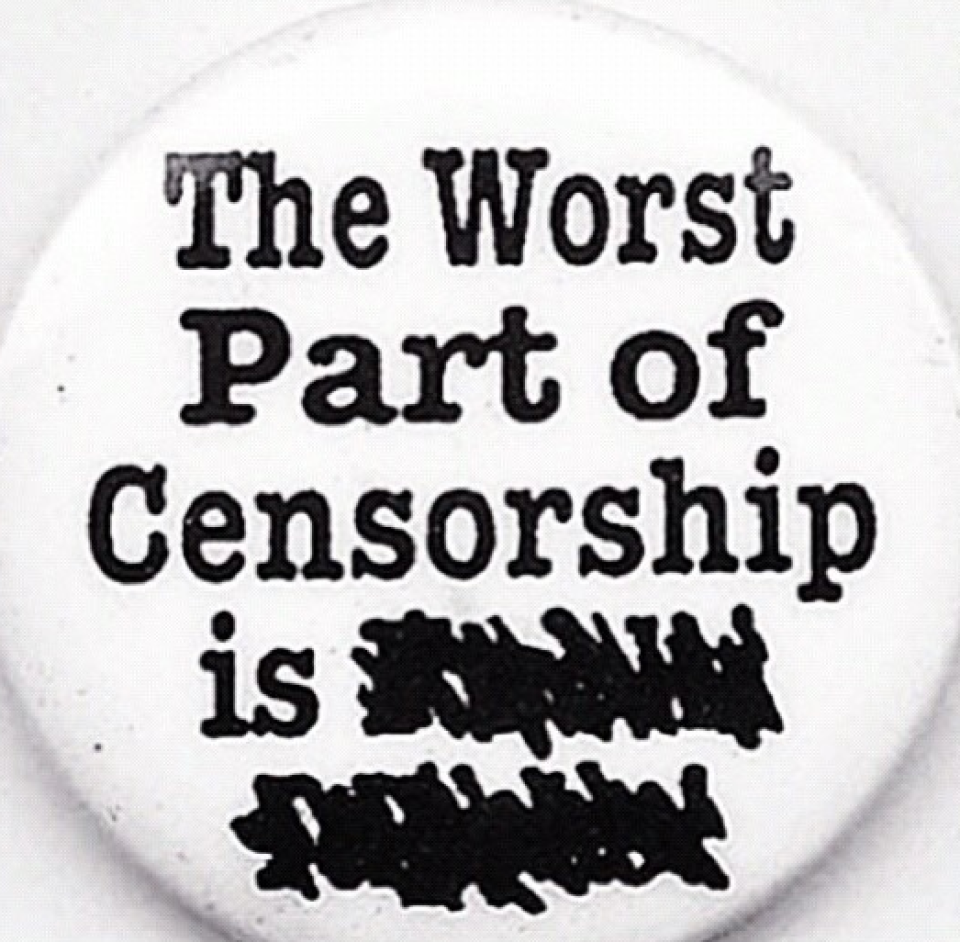

One, social media platforms are censoring sexual speech. All the five incidents above are cases of private censorship, an everyday form of censorship that we increasingly face in our daily lives. It doesn’t matter who’s doing the blocking – a government or a corporation; it’s still censorship. Private censorship. It doesn’t matter whether we live in open societies famed for upholding free speech or societies that are more closed and less tolerant of free speech. Private censorship affects everyone who uses online platforms.

Two, these private players are censoring speech that is not harmful in the least. I’d call all of these sexual expression or sexual speech, and protect it as part of free speech and free expression, instead of muzzling it for some imagined harm. What’s the harm in any of these? None of these forms of expression cross the lines between coercion and consent, unlike the recent online spillage of nude photos of female celebrities – without their consent. Now that’s harm, not this.

And, in an aside, don’t miss that some of these platforms continue to host pages that can cause actual harm. “As rockets rain on Gaza, Facebook does nothing to stop hate speech against Palestinians,” Global Voices noted in July. “Until our boys are returned – we will kill a terrorist every hour” appeared on Facebook.

And please, if this is obscenity in an age when sexual explicit images and nudity are as common as tap water, well then, we need new words for a digital age. Type ‘female Indian nude’ into Google Images and you’ll get my point. In any event, as free speech groups like the American Civil Liberties Union have often noted, Justice John Marshall Harlan’s line, “one man’s vulgarity is another’s lyric,” sums up the impossibility of developing a definition of obscenity that isn’t hopelessly vague and subjective.

Three, is social media censorship even constitutional? Or are social media platforms removing material that is constitutionally protected and that courts might have upheld as free speech? This is the question Marjorie Heins raises in the Harvard Law Review, noting that free speech is increasingly being curtailed by online ‘terms of service’. (Ah yes, ‘terms of service’. Please tell me you’ve given your informed consent to these, which means you’ve read every word of the legalese intended to protect platforms, not users.)

For example, “most of what Facebook proscribes is protected by the First Amendment” in the United States. “Despite their good intentions and their claims to a free-speech-friendly philosophy, these companies employ ‘terms of service’ that censor a broad range of constitutionally protected speech.” Heins goes on to quote influential legal commentator Jeffrey Rosen who once said that Facebook wields “more power [today] in determining who can speak… than any Supreme Court justice, any king or any president.”

Four, is Silicon Valley unable to deal with female sexuality? As one commentator wrote in the aftermath of Happy Play Time’s rejection, “Gong’s recent travails highlight a glass ceiling in the tech world – start ups and entrepreneurs are encouraged to break all manner of boundaries and let the chips fall where they may with such regularity, words like “innovation” begin to lose their meaning. But when it comes to sex and tech, they’re stonewalled.”

And five, and most insidious of them all, social media is not just censoring us, but turning us – yes you, me, everyday users – into censors. Click the Report Abuse button to report something that isn’t necessarily abuse and voila! you now have the power to block another user with a click or a swipe or enough clicks that you can hustle up. Everything that gets reported or labelled abuse may not be abuse, but may still get blocked if enough users call it in.

So this, to use a dollop of Trollope, is the way we live now. Online media platforms, like Tolkien’s winged Nazgul, increasingly shaping and defining everything from what speech is kosher to what is abusive, whether or not you can breastfeed or show a nipple in public, whether you’re too fat or not, whether you’re a ‘good girl’/rulekeeper or ‘bad girl’/normbreaker, and even deciding whether or not you can privately masturbate with a digital aide.

And of course never telling us why they do what they do.

Welcome to this #BraveNewWorld.

Image by Pedro used under Creative Commons license

- 9607 views

Add new comment