This year’s Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) outcomes set off some alarm bells of concern about the lack of political space for civil society in the CSW process. This becomes even more troubling when we take into consideration the growing challenges to political participation and freedom of expression internationally. Although it is of vital importance for critical voices on the ground – those that speak from “the belly of the monster” as Donna Haraway would put it – to actively participate in all CSW processes and negotiations relevant to the implementation of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, this year that has not been the case.

While the Commission adopted a Political Declaration that reaffirms states’ commitment to Beijing, it failed to confront the real challenges that women and girls around the world face at this very moment. Its exclusion of women’s organisations, and women’s rights activists around the world brought outrage from all those committed to challenging inequality on the ground and contributing to the transformative changes necessary in order to fully implement the human rights of women and girls.

In light of these recent developments, Lamia Kosovic conducted an interview for GenderIT.org with Joanne Sandler, a Senior Associate of Gender at Work and former Deputy Executive Director of UNIFEM, to hear her personal opinion on the issue at stake.

Lamia Kosovic: In her article CSW59 – Beijing Betrayed, Naureen Shameem states that civil society voices, that is, women’s rights and feminist groups, were largely excluded from the Commission’s working group and process. Shameem implies that this year’s Political Declaration is rather general and weak, and that it neglects the links between the work of the CSW and many other international human rights bodies, mechanisms and policies. What do you think about it? How can we locate our struggle as feminists in spaces like the CSW given the complaints and anger that were raised regarding the working group this year?

Joanne Sandler: Shameem’s analysis of the Political Declaration was widely shared by many women’s rights activists attending CSW59, articulated pointedly by Lydia Alpizar in her statement at the opening of the CSW, by Shawna Wakefield in her blog post for Oxfam, and by the hundreds of civil society groups that signed a joint declaration of protest. I suspect more criticism of this type is forthcoming. And it’s necessary.

There are many feminists and feminist organisations that have given up on the CSW and other intergovernmental processes hosted by the United Nations. The frustration is understandable – largely rhetorical statements are made by governments, there is shrinking space for influence of NGOs, and fear of right-wing and extremist backlash results in apolitical (or “ahistorical” as Shameem refers to them) declarations like the one emanating from CSW59. Yet, I continue to believe that this is an important space for feminist organising that we have to re-claim.

The CSW is a quasi-barometer of the pace, progress and petulance of governments over women’s rights. When we struggle at the CSW over language relating to women’s human rights defenders, to the meaning of families, to the importance of reproductive rights, we are engaging in feminist struggles. We may be witnessing backlash and backpedalling, but that’s an “up-close and personal” experience of what is happening to feminists every day in many parts of the world. The CSW unmasks state positions and shows how far different governments are willing to go for gender equality. I can’t think of any other venue besides the CSW where we have the opportunity to delve into gender equality language and nuance with governments and a whole range of opposers and supporters. How can we maximise that unique opportunity? The “rules of the game” – the way that political agendas get set and negotiated in the UN – are increasingly stacking up against a strong voice for civil society in venues like the CSW. We need to change them.

We need to re-think, not to de-link from, the CSW. We need to work closely with UN Women, supportive governments and other partners to keep pushing to change rules that exclude civil society from meaningful participation in negotiations. For one, this should be at the top of the agenda for UN Women’s Civil Society Advisory Groups (CSAGs). We need to look at other intergovernmental processes that offer greater space for NGOs and push for those precedents to be used during CSW. We need to maximise use of ICTs and media to create inclusive, participatory and transparent processes. We need to support far greater numbers of young feminists to attend CSW and bring new generations of organising to the preparations, the event, and its follow-up. And we need to engage in political strategising around both the content and process of the CSW as a feminist political force.

LK: Which would you consider were the real advances during the 59th session of the CSW in terms of the re-prioritisation of Section J of the Beijing Platform for Action [on women and the media], if there were any?

JS: I can’t think of any substantive issues that were advanced by this CSW, other than an overall affirmation of the centrality of gender equality and women’s empowerment. I’m sure that many feminist alliances and initiatives were sparked by informal sessions and hallway conversations, but I didn’t get a sense of any particular movement on specific issues. There was affirmation but no re-prioritisation that I was aware of. We would need a different kind of space for that.

LK: Governments agree on the struggle to “dismantle patriarchy over the next 15 years”, as the Executive Director of UN Women Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka said. How can we provide clear, action-oriented and sustainable links between Section J and its connections with patriarchy? What would be the strategies to bring Section J right to the centre of debates and action?

JS: While UN Women’s Executive Director spoke truth to power by calling for the dismantling of patriarchy, I’m not sure that we can characterise that as governments agreeing. What they agreed to was a lukewarm political declaration and a contested set of working methods for the CSW.

The links between Section J and patriarchy need to be high on the agenda of feminists worldwide. The growing consolidation of power over the governance of technology, ICTs and media by multinational conglomerates and elites is a clear manifestation of patriarchy. Feminists have been joining with other social justice movements to confront this, as we’ve seen in the organising for the World Summit on the Information Society. One problem is that there are too few feminist activists that are engaged with where the opportunities for change are emerging and that prioritise intergovernmental opportunities like WSIS. We haven’t yet seen feminist organising to challenge the patriarchal nature of ICTs and media in the same way that organising has happened around reproductive rights, ending violence against women or other feminist issues.

We’ve been talking about how to bring Section J to the centre of feminist strategising and the post-Beijing agenda for more than a decade now. APC has done great work on this, with a small number of other organisations. We need a larger alliance of feminist groups – working closely with other social justice networks focused on ICTs – that are prioritising this. If we think about how other issues (like maternal health, ending VAW or others) gained traction, attention and resources in global venues, we could consider: a) demanding that the UN Secretary General undertake a global study on the way that gender discrimination is perpetuated by ICTs and media and how it can be harnessed as a force for positive change; b) using venues like the upcoming AWID meeting or other regional and global spaces to strengthen the feminist political agenda around Section J; c) strengthening initiatives like the WACC Global Media Monitoring Project so that there is a day or week where feminists across the globe are organising around ICTs and media and this organising generates knowledge and awareness about the political stakes in countries worldwide; and d) doing some high-profile feminist confrontations and dialogues with ICT and media moguls. If we could organise some feminist “encuentros” with those who control these spaces and bring that dialogue to CSW and other venues, it could be powerful.

There could be many more ideas. Advocating for a Fifth World Conference on Women would put a much higher priority on gender and ICTs, since many of the issues that we now know affect women’s human rights were not as familiar in 1995. We need to do everything possible to keep creating spaces for political strategising between feminists from around the world for Section J and for the sections that have yet to be written.

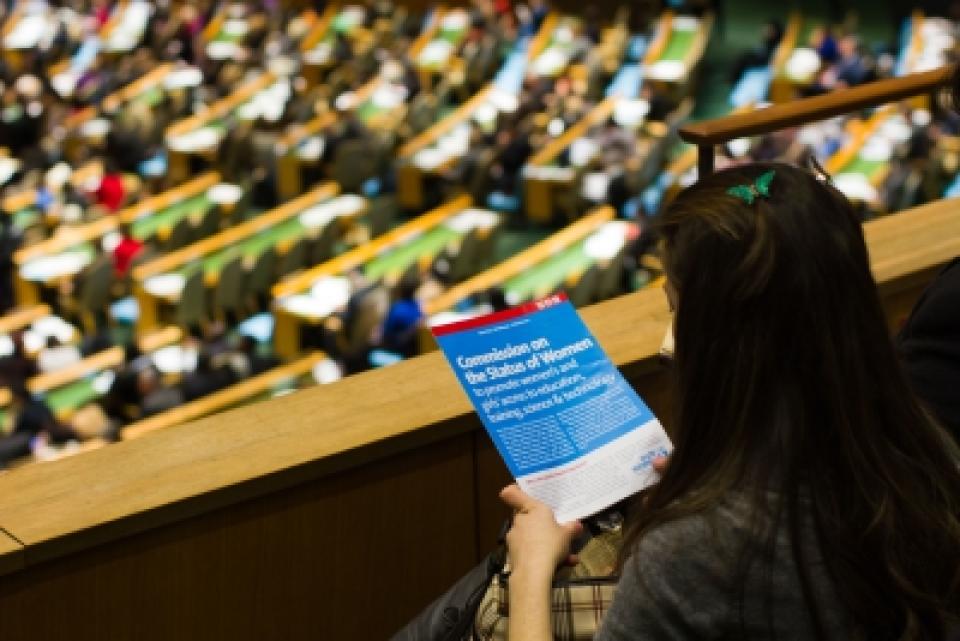

Image by SustainUS used under Creative Commons license

- 10276 views

Add new comment