As a teenager, when my friends swapped fantasy and sci-fi books, I was engrossed in online forums. While they would lose hours devoted to fictional worlds, I was fascinated by the snippets of everyday life I found on the web. There were many "worlds" out there – so many lives I wanted to imagine – and on the internet, I could access them in a matter of clicks.

There was a website I particularly liked to visit, full of submissions about first times. I read and re-read accounts of first sexual experiences, queer attractions and a multitude of other milestones. In my university days, I would occasionally return to the blog, phone in hand, when I couldn’t sleep. I felt a connection to the anonymous submissions and liked to imagine who might be on the other side. I gave the voices the faces of people I knew. While I was uncomfortable to talk about sex and sexuality openly, even with my friends, in this corner of the internet, I had found a portal into those conversations.

The online world gives access to narratives that make us feel validated in our skin. We make homes out of the sites we frequent, and develop kinships with people we will never meet, perhaps. Because of this, last year, I was distraught when greeted with an error message on the faithful first-times website. After years of finding the blog a soothing space, it was gone. The administrator had deleted it.

The loss of the blog stacked atop many other forms of grief I was experiencing in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was like (the too-recent) history repeating itself: at any moment, something you have come to see as fixed and certain could be taken away. While I could not point at what I had lost, I was mourning something. I felt a sense of urgency to honour it; to have something to show for the webpages that had carried me through my early adulthood. This led me to reach out to three African women who curate digital archives, and to try to put into words what these kinds of sites and stories mean to us.

“It's like losing your belongings in a fire. It's something out of your control, like an act of God.” Malaka Grant, cofounder of the Adventures from the Bedrooms of African Women blog, could relate to my loss. In 2018, her Facebook account was deactivated, with no explanation as to why. “I'd had this account since 2003 – since before my children were born! This is now 15 years of pictures – the birth of my children, my wedding, my vacations, [gone].” She had always seen the internet as a safe place for her memories. “[I thought] I'll just store all my pictures on Facebook because Facebook isn't going anywhere.” And the shock was still fresh. “It was an archive and that archive was ripped out from under me.”

“It's like losing your belongings in a fire. It's something out of your control, like an act of God.”

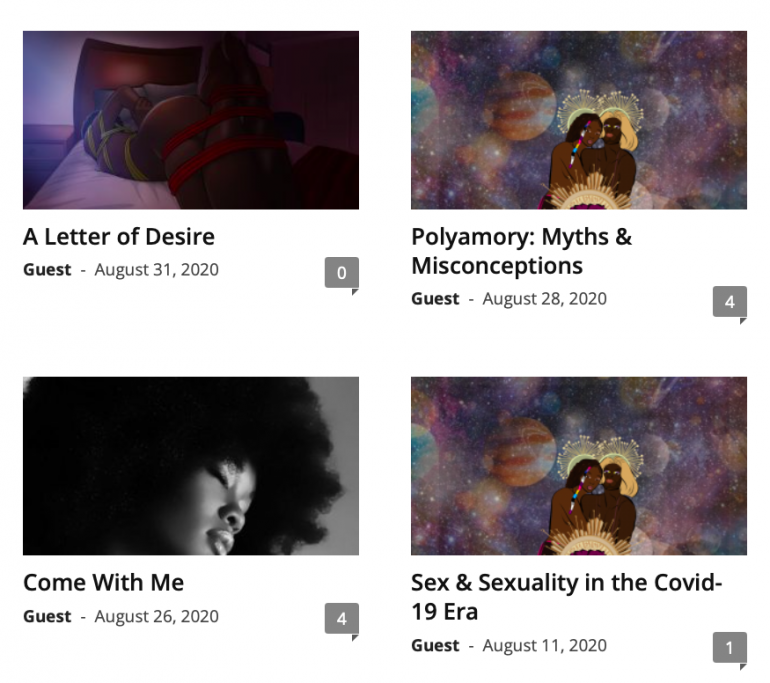

Experiencing a loss of this kind wakes you up to the cumulative weight of the individual bodies of data. When you upload one photo or read one piece of writing at a time, you seldom think of what those pieces will come to mean when they become whole. Malaka admits that when she cofounded the "Adventures" blog with Nana Darkoa Sekyiam in 2009, she couldn’t have imagined what it has become now. The blog, which houses writings by African women about sex and sexuality, has over 1,000 submissions to date. “I didn't anticipate how much it would mean to so many different people,” Malaka told me. For some contributors, the blog was the first place they had ever published anything publicly.

Over the years, the blog has been widely recognised for breaking taboos and putting pleasure at the forefront of conversations about African women’s sexuality. “For us, in West Africa, we don't really talk to our parents about sex. It's something that you fumble your way around,” Malaka said, “So when a kid comes to us and says this blog has been constructive and educational for them, it feels good.”

Screenshot of the Adventures from The Bedrooms of African Women website, showing recently published submissions.

It goes without saying that using an online platform has widened the reach of the "Adventures" project and made it interactive. “People can access it whenever they want to, wherever they are – on their mobile devices, their laptops,” Malaka says. “[We] were able to get access to many different types of voices from many different places.”

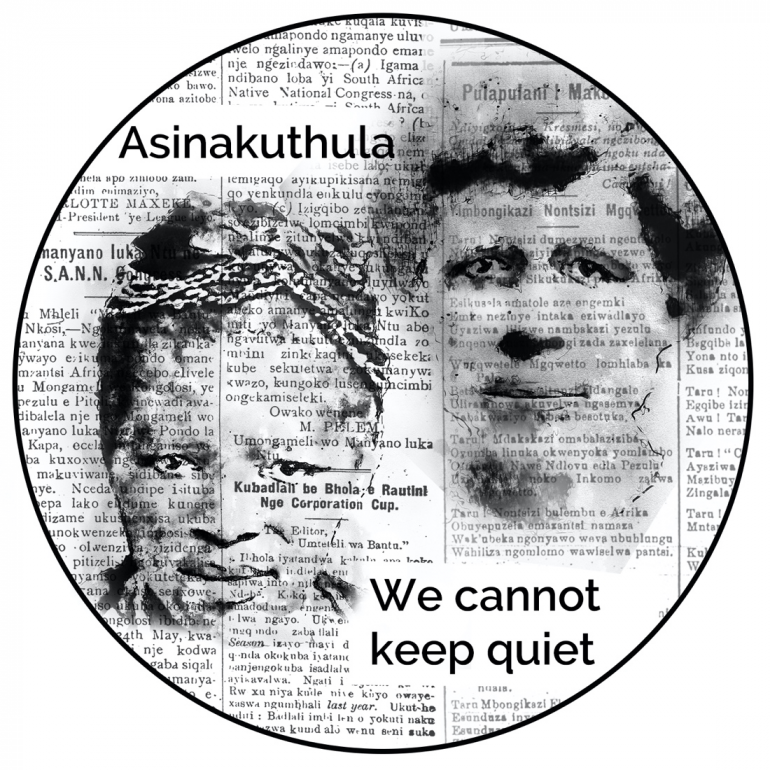

The potential to have this kind of reach is one of the reasons Dr. Athambile Masola, founder of the Asinakuthula Collective, is thinking more about her practices of digital archiving. Asinakuthula Collective is a group of students, teachers and creatives whose aim is to shed light on the legacies of African women. Thus far, their focus has been hosting public events and producing publications that centre Black, African women’s histories. With their developing online platforms, including their website and Instagram page, they are aiming to build a resource hub that can be used to educate people about the role African women have played in history. “I'm now realising more and more that the internet is probably gonna always be with us, [so I’m] trying to find ways of organising that knowledge,” Athambile says.

Athambile’s work with Asinakuthula Collective builds on the efforts of writers before her to archive Black women’s stories. “Of course, I'm using the internet but Women Writing Africa [did] this in their anthologies,” she says. On her motivation for creating this digital archive, she says she is “responding to the little girl who never saw Black women in her education.” She adds, “I'm hoping that parents are Googling and researching and [that] they'll stumble upon Asinakuthula's website, and find a world for black girls who want to know about Nontsizi Mgqwetho who was writing poetry in the 1920s.”

The Asinakuthula Collective’s logo. The logo features images of writers Charlotte Maxeke and Nontsizi Mgqwetho, as well as images of their words from their 1920s articles in the newspaper Umteteli waBantu.

Athambile’s academic research focuses on the life and writing of Noni Jabavu, a Black, South African woman whose writing was published internationally in the 1960s. Athambile’s interest in Jabavu’s history was sparked when Athambile, at the time a columnist for a local newspaper, discovered that Jabavu had written for the same paper four decades earlier.

When Athambile started writing for the newspaper, she was uncomfortable about some of the reactions she received: “People were making such a big deal out of the fact that I was one of the few Black women writing and it just felt uneasy cause I've never liked this idea of being the first of a few of the only.” In seeking out Black women writers, and then coming across Makhosazana Xaba’s writing on Jabavu, Athambile’s intuition was affirmed that writing came naturally to Black women.

She is cognisant of what is at stake here. As Black, African women, our contributions to political life are routinely undervalued and erased. For Athambile, this erasure is what fuels narratives of exceptionalism: the idea that marginalised people who manage to rise through the ranks are different from and superior to their counterparts. “I think it's a ploy of white supremacy to make us feel like we're exceptional because then [it means] we have no history.” Athambile says. “Their whole aim is to make us feel like we're starting from scratch when we're not.”

For Yolanda Dyantyi, digital archiving is a way of documenting our resistance: something inspired by her personal experience. “I don't want my contributions to be forgotten,” she tells me. Yolanda is currently the executive director of Archive Amabali Wethu, a digital media organisation that tackles gender-based violence through creative and archival work. It was founded in 2019 by Yolanda alongside Ciko Sidzumo and Nonhle Skosana, who have since left the organisation.

A few years before Archive Amabali Wethu was founded, Yolanda was expelled from Rhodes University following her participation in the #RUReferenceList student protests. The protests were against sexual violence at the university and the university administration’s failure to address it. Since then, Yolanda has been pursuing legal action against the university contesting her expulsion. This history feeds into her work with Archive Amabali Wethu.

“Why I envisioned this – I felt like with the work of #RUReferenceList, there were a few individuals […] trying to ensure that its memory doesn't fade away,” Yolanda reflects. “Throughout the years, I felt that there was something important about ensuring that your story lives,” she adds. Archive Amabali Wethu’s mission broadens this: "amabali wethu" means "our stories" in isiZulu.

For Archive Amabali Wethu, the focus on creating a digital platform was instinctive. "We were [inspired] by how other movements in the past five to 10 years in contemporary South African politics have been influenced by social media," Yolanda says. “#RUReferenceList was a movement that initially began on social media, inciting this protest and motivating women to break the silence [around rape].” She continues, “The hashtag in of itself is able to archive [and] with those movements that started online, we are able to easily access those archives and follow the story as it develops."

The biggest block in Archive Amabali Wethu’s path is lack of funding. As a non-profit organisation, it is largely dependent on grants which are an unstable source of income. Not only are grant application processes time consuming, but even when successful, grants are often awarded on a short-term or once-off basis.

Yolanda is hoping to get a consistent source of funding so she can see the organisation’s mandate through. Ideally, if successful, she would still have creative control over the content produced. Another drawback of external funding is that it sometimes carries terms and conditions that may constrain the recipient. Malaka tells me that the "Adventures" blog was financed by its funders until 2019. "Because we were self-funded, we were self-directed since the beginning," she says. By the time the organisation received external funding for the first time, a decade after they were established, their values were clear and non-negotiable.

Digital archiving is “a labour of love” Athambile says, “cause sometimes, many of those hours are not paid for.” The first thing required of archivists, Athambile thinks, is “the aptitude to be curious.” She continues, “There's almost like a tenacity and a temperament that archivists need to have…. It's like a muscle that you must build.” She gives the example of the process of writing about Noni Jabavu. By the time Athambile starts writing an article about Jabavu, she says, she has taken apart bibliographies and followed numerous sources in order to find physical copies of Jabavu’s writing. She likens it to going through a maze: “You're following threads,” she says. “You're not quite sure where they're gonna go but you follow them anyway.” The process of finding and consolidating this information takes up the majority of Athambile’s time.

Digital archiving is “a labour of love.”

It’s also about who you know and what they know: “Half of the work of an archivist is having a network of people and building that network as well. They don't talk enough about that,” Athambile says. Through networking, she has met people who have helped her understand the workings of physical archives, those located in universities specifically. “This particular archive is also about access,” Athambile says. Because she worked as a researcher in a university, she was able to access archives like these with relative ease.

“It's also collective labour,” Athambile says. Without the other members of Asinakuthula Collective, Athambile would not be able to do this kind of work. What makes it possible is finding collaborators, she says: people willing to share their knowledge, time and resources with you.

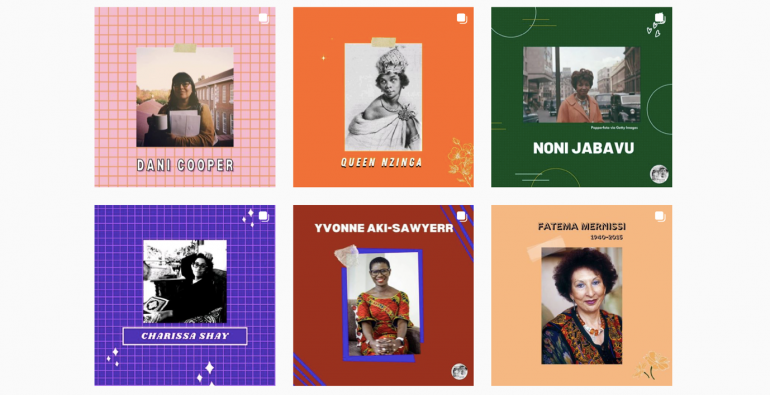

Screenshot of the Asinakuthula Collective’s instagram page. On it, they feature profiles of different women, including historical African figures and the Collective’s members.

If, like Archive Amabali Wethu, you tackle gender-based violence (GBV) using an online platform, there is an added challenge: the ever-present threat of online violence and censorship. “[When] you look at the content that gets banned [on social media platforms], it's people who are overtly speaking out against social injustices,” Yolanda says. Last year, the organisation’s Twitter account was suspended: “It was very infuriating. Without warning, we were silenced.” She is acutely aware of how taking a stance against GBV puts the organisation in the line of fire: “The threat of being silenced, in the form of being blocked or having your account deactivated, is still there… That’s a symbol of patriarchy clamping down on opposing views against it.” Despite this, she is forward-facing. “I still believe that the internet is a platform with huge potential for us to express ourselves,” she says.

As our digital archives grow, so do the communities we build around them. Malaka recounts, “One of the things we love most about our Adventures community is that in the early days, [when] the trolls used to come onto the blog, our community would swoop in to say ‘There are a thousand other websites for you to go, and if this space is not for you, it's not for you.’” This was an unexpected gift for Malaka: “knowing that we're sisters in arms and that we're going to defend each other digitally."

To build a digital archive is to fill gaps of knowledge, and in our context, this refers to gaps about African people and their experiences. Athambile came to realise this when she was thinking about the impact of Makhosazana Xaba’s work on Noni Jabavu: “It mattered that [Xaba] had written a [master's thesis] on Jabavu and that we all get to have that.” Athambile reflects, “There's a whole lot of scholarship around Cecil John Rhodes and there's a reason we still know his name – people built institutions around him.” She continues, “Equally, that's what we do for Black women. […] In order for people's names to be remembered, you build something around their stories.”

On the African content, and in South Africa specifically, the lack of access to tertiary education remains a big problem. Thus, relying on archives which are only accessible through academia only replicates already existing inequities. “If we start thinking of different ways of having knowledge producers outside of academia,” Athambile says, “my vision is for Asinakuthula to become an institution… Building Asinakuthula to be able to do that work outside of academia is the long-term thing. That's part of the capacity building.”

Yolanda shares a similar vision: “I believe in the importance of building a point of reference for the generations that are to come after me – a library of sorts for people to refer to.” She also views this work as a form of research. “We believe in this process,” she says, “that this form of gathering knowledge – experiential knowledge – should be valued.” Ultimately, Yolanda wants to build the archive up to the point where it has the logistical and digital capacity to take submissions from people across South Africa, documenting the resistance work being done in their communities.

“Another thing we're trying to touch on is that not everybody's mode of learning and unlearning will come from reading,” Yolanda says. For this reason, Archive Amabali Wethu creates content in different forms, and so far, this includes podcasts and video reports. “If we can bring these modes of knowledge consumption under one space – accessible online – then we will be happy,” Yolanda says.

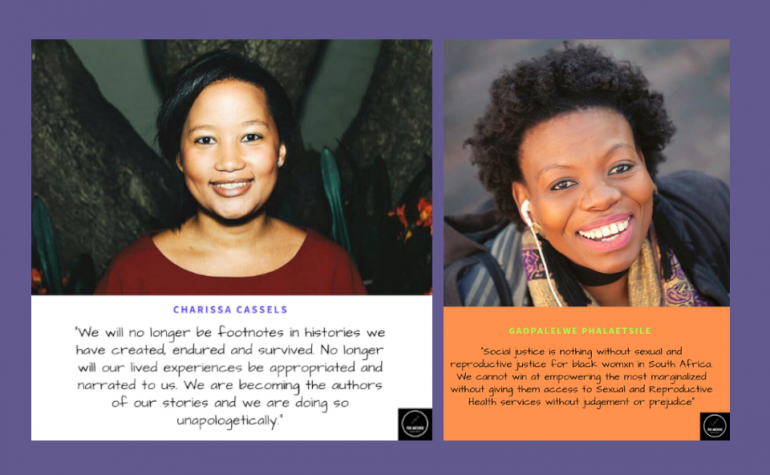

Images from Archive Amabali Wethu’s Quotes by Black Womxn project. The project aims to archive quotes by black women, non-binary and LGBTQI+ individuals.

Charissa Cassels (left): "We will no longer be footnotes in histories we have created, endured and survived. No longer will our lived experiences be appropriated and narrated to us. We are becoming the authors of our stories and we are doing so unapologetically".

Gaopalelwe Phalaetsile (right): "Social justice is nothing without sexual and reproductive justice for black womxn in South Africa. We cannot win at empowering the most marginalized without giving them access to Sexual and Reproductive Health services without judgement or prejudice".

In addition to access, we need to think about how the digital world evolves and how this evolution impacts our digital archiving practice. Malaka recounts, “I found a floppy drive in my purse from [when I was in] college. At the time, I thought, "This will be forever," but where am I gonna insert a floppy drive in 2020?” She continues, “It raises a lot of questions about how we can store things in perpetuity, or what you think is perpetuity.”

“Every time I get the notification ‘Your memory is almost full’ I kind of panic, because if my memory is almost full, I can't store anything in there,” Malaka says. “It has an actual human connection.” She continues, “It makes me think about the importance of making sure we record our information, that it's safe and accessible so that when someone like me, in 20 years, wants to read thoughts from a Black woman […] she'll be able to find [them].”

“We should do everything we can not to play a part in our own erasure, unintentionally,” Malaka says, “and think about the long-term effects before we hit ‘Delete’ on something.” After all, when we create and share our stories online, we can’t know the full reach and impact that is has. “That's the kind of beauty and the strangeness of the work,” Athambile says. “I'm becoming more and more inspired by knowing our work travels. That's one of the things about the internet, it travels farther than we actually think.”

Speaking to Malaka, Athambile and Yolanda helped me understand what I had lost when the blog that inspired all this was deleted. There is a whole other world I inhabit in the digital space and in it, this was one of my favourite places. Online spaces like these are not insignificant. In African societies, wherein gender and sexual minorities still face layers of discrimination, the internet can be a dreamscape where we reach for freedom.

In African societies, wherein gender and sexual minorities still face layers of discrimination, the internet can be a dreamscape where we reach for freedom.

While reflecting on these interviews, I also came to appreciate the commonality between the loss of the blog and the other losses of the COVID-19 pandemic. The centrality of care became a recurring thought. Whether it is adjusting to wearing masks or strategising on how to protect our digital memories, care is collective work. One year into the pandemic, it is clearer than ever that we survive through care; that we survive through caring for each other and through caring for the things – digital and otherwise – that nourish us.

- 5267 views

Add new comment