Original illustration by Neema Iyer for this edition of GenderIT. License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA.

At the Making a Feminist Internet in Africa convening (#MFIAfrica), held at the end of October 2019 in Johannesburg, a group of over 50 activists and scholars from the region met to brainstorm how we would materialise the Feminist Internet. During the convening, we found that, despite our different backgrounds, we shared common struggles in organising against the various oppressions that face us. Further, it was quickly evident that our visions for emancipation, as LGBTI, gender-diverse, African people were inextricably linked with the existing vision for a Feminist Internet. In the same way that we cannot separate our digital bodies from our physical bodies, we cannot separate our online movements from the resistance efforts we lead offline, and while we explored together what it means to build a movement, I was struck by the many ways in which recovering from ruptures emerged as a core theme in our conversations.

In order for our movements to be successful, not only do we have to find each other, but these connections have to be sustained with intention. Within our movements, we are faced with internal challenges because every movement is founded on relationships, and relationships are vulnerable to all kinds of challenges. From our reflections in this regard, we delved into discussions about the factors that cause ruptures within our movements, and brainstormed how we could work to ensure that a rupture does not become the destruction of the entire movement. Here I will reflect on the different kinds of ruptures we discussed: interpersonal conflict, activist burnout, erasure, and ruptures across locations.

Dealing with interpersonal conflict

What brought us together was an interest in the internet. For some, the internet had been a long-time companion, while for others, it was a site of curiosity. In any case, in a room of people from over 18 different countries, all with their own individual journeys, on the surface, we had more differences than similarities. This was not unlike many socio-political movements, wherein people from diverse backgrounds might gather to advance a shared cause. In itself, the convening was a microcosm of the movements we are part of, in that as much as there was potential for growth, the ground was also fertile for misunderstandings and disagreement.

In itself, the convening was a microcosm of the movements we are part of, in that as much as there was potential for growth, the ground was also fertile for misunderstandings and disagreement.

My first observation in this regard was that accepting the possibility of disagreement, rather than avoiding it, is actually in itself a way to build resilience for when conflict occurs. In some of the feminist movements I have been part of, the initial fuel of the movement was the similarity in political views amongst members, which is understandable especially when a movement comes together spontaneously. Unfortunately, this means we did not take enough time in the beginning to plan for how we would handle conflict, almost assuming that we did not have to worry about it. In the end, the movement fell apart because we were unprepared when conflicts emerged. The convening itself modelled for me how this kind of situation could be addressed: by setting out the parameters of how we would engage with each other from the start. I came to see that when it comes to dealing with ruptures, as the adage goes, prevention is better than cure.

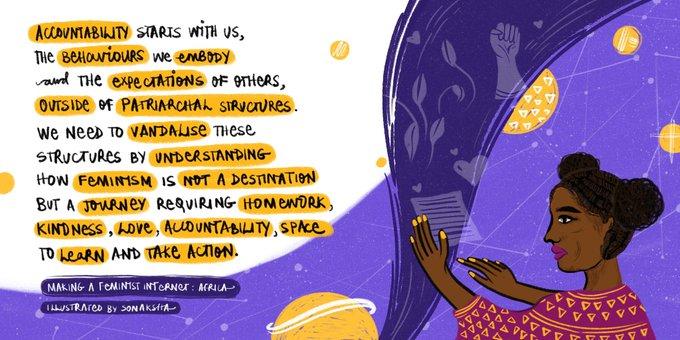

One aspect we discussed about safeguarding our movements from the ruptures of interpersonal conflict was that of accountability; how important it is to stitch ethics of accountability into every corner of our organising. Having strong accountability structures from the onset – whether in a spontaneous protest or in formal institutions – is paramount to any sustained collective action, as it enables us to build from past experiences. When things do not go according to plan, when we have interpersonal conflict, accountability – both on a personal and an organisational level – can determine the future of a collective. Especially when movements come together spontaneously, discussing accountability ensures that interpersonal problems are seen as an inevitability, and rather than threatening the entire movement, we can turn to agreed-upon accountability structures to hold us together.

When things do not go according to plan, when we have interpersonal conflict, accountability – both on a personal and an organisational level – can determine the future of a collective. Especially when movements come together spontaneously, discussing accountability ensures that interpersonal problems are seen as an inevitability, and rather than threatening the entire movement, we can turn to agreed-upon accountability structures to hold us together.

One of the breakaway groups created a statement to represent what accountability means to them. Participant @SeyiAkiwowo tweeted their statement, which was later turned into an illustration by artist Sonaksha Iyengar.

Another strategy we discussed for dealing with ruptures, which is tied to accountability, was practising transparency and responsibility when it comes to power relations. Many participants at the convening spoke to this, highlighting the need to consider how our varied locations, our capacities for access, and our social positions inform our actions and views. We spoke often about the need for us all to take responsibility of the privileges we have; to wield the personal power we have carefully. As one of the participants said, “Feminism is homework” and part of the task is self-accountability.

A focus on founding principles

The discussions at #MFIAfrica served as a first step in figuring out how to balance accountability and care, whilst still making gains towards our aims. From early on, we established principles of participation, by sharing with each other what would make us feel safe. From this, we co-created a blueprint to guide our interactions. On top of wanting to feel safe, we also desired to learn from each other, and established kindness as a core principle in our interactions. In a later conversation we had about the role of romance, friendship and sex in organising, it also came up that a focus on the founding principles of a movement can be used to deal with rupture. For instance, values such as love and care, which often serve as the heartbeat of organising, can be drawn on when we need to work out how to deal with conflicts amongst ourselves.

The discussions at #MFIAfrica served as a first step in figuring out how to balance accountability and care, whilst still making gains towards our aims.

In thinking through how to handle breakdowns of trust within movement building, we realised a unique opportunity: the chance to be creative about how we respond to ruptures. In our everyday contexts, we are governed by states, many of which have centralised justice through policing and the legal system. As feminists, we have the opportunity to implement approaches which work against the logic of forms of domination such as capitalism and patriarchy; which remain true to our principles. One of the suggested resources for thinking through this was the TransformHarm.org website. TransformHarm.org provides resources to end violence which rest on the principles of community accountability, healing and justice. Through sharing and building on such resources, there is potential for us to move away from re-enacting violence against each other.

Developing resistance against activist burnout

As dedicated as we are to the intersecting movements for freedom in our contexts, a big problem we face as a result is emotional or physical burnout. The oppressive systems we mobilise against are powerful, and they mutate every day to reinforce their power. In comparison, our energy as individuals is finite and thus, activist burnout seriously threatens the continuity of movements. In response to this, it is crucial to use the power of collectivity to prevent burnout. This may look like making explicit what capacities you can and cannot offer to the movement, as well as taking time away from organising when needed. This works best, as with other proposed strategies, when practised continuously: as one participant said, “I don't think self-care should only come when you're really burned out. It's about creating a lifestyle that you don't have to escape from."

In the discussions about activist burnout, one participant suggested referring to the work of The Nap Ministry as a learning tool. The Nap Ministry is a community-centred online movement which advocates for consideration of the political power of rest, particularly for activists and people in marginalised communities. In their words, “Rest is a form of resistance because it disrupts and pushes back against capitalism and white supremacy.” Another suggestion that came up in the conversation was appealing to funders and donors to provide institutional support to enable activists to rest. For instance, this could be done through instituting “flexi-hours” in the organisation, and providing funding to enable sustained wellness and care initiatives.

“I don't think self-care should only come when you're really burned out. It's about creating a lifestyle that you don't have to escape from."

While many of our conversations at #MFIAfrica were about the internal politics of our movements, the necessity of our resistance comes from external sources. The reason we need strong movements is because, globally, elements of fascism and oppressive control are relentless in their efforts to contain those of us who do not toe the line. The online sphere is reflective of this, as activists often encounter forms of violence, like doxing and harassment. As a result, to engage in online activism and movement building can put us at risk of violence, and without adequate resources to remain safe online, we are vulnerable to being pushed out of the space and losing connections in that way. There can be a great emotional toll of being vocal and organising online, and this needs to be recognised as a source of ruptures in feminist movements. In responding to this, one of the strategies we can use to maintain our movements is ensuring we have strong offline support networks, so that we have a safe space to retreat when the online sphere becomes dangerous or overwhelming.

Confronting the ruptures within intergenerational relationships

In the plenary sessions we had at #MFIAfrica, I noticed that the topic of intergenerational disconnection resurfaced often. There were strong concerns about how feminist movements of this era have lost connections with those who paved the way for us. This was a difficult topic, as it involved also admitting the difficulties we faced as young feminists when interacting with older feminists. Whilst there is a huge opportunity for knowledge to be shared between generations, we struggle to meet each other, especially when we disagree on how things should be done.

Many participants spoke about the importance of building structures to facilitate a connection between younger and older feminists; ensuring that we heal the ruptures that have disconnected different generations of activists. In South Africa, one promising example of the possibilities of bridging the intergenerational gap is Shayisfuba. Since 2019, the #Shayisfuba collective has been organising across provinces, to create and lobby for a feminist government. The collective comprises women and non-binary people from different spheres and of different age groups.

Many participants spoke about the importance of building structures to facilitate a connection between younger and older feminists; ensuring that we heal the ruptures that have disconnected different generations of activists.

Another suggestion from participants about bridging the gap was to start developing advisory boards or informal mentorship structures, to maintain links and strengthen our knowledge bases. As one of the participants said, strengthening these ties would also help build resistance against burnout: “As part of self-care, there’s the idea of succession planning; thinking about who you might end up passing the baton onto.”

Bridging gaps in political memory together

In addition to the above, we agreed that it is important to address ruptures in memory by dedicating ourselves to archiving our movements as well as those which cleared the paths for us. In speaking to this, the APC team led a Museum of Moments exercise, where together, we documented significant events of the past few decades, relating to gender, LGBTI rights, internet freedom and their intersections. Preserving memory is important for the sake of us knowing our history; in conscientising us of the battles that have been fought for our freedoms. But also, it is vital to know what has and has not worked in countering oppression; especially in order for us to avoid repeating ineffective methods. As a matter of strategy, preserving memory and being aware of our histories enables us to care for ourselves better, in that we know how to direct our energy to where it counts. In this way, we also are able to take care of ourselves better.

Connecting across locales

The convening brought together people from all corners of our vast continent, mirroring the kind of barrier-breaking ways the internet can connect people. The way we were able to connect through #MFIAfrica brought home the many struggles we share, and it was evident in the organic conversations we had in between plenaries that we had a lot of valuable information to share about organising in our contexts. Not often do we have the chance to convene in this way, and in cherishing this, we thought about the need to connect more across territories. Across physical borders, as well as urban and rural divides, there are many opportunities for us to leverage our (relative) access to advocate for those in territories that are unconnected to get access to the internet. Additionally, it is imperative for those of us in transnational movements, which tend to get more attention than grassroots movements, to amplify work that is being done at grassroots level in our contexts. In doing this, we spoke to the potential for us to leverage the internet as a tool to strengthen our movements by breaking down silos when it comes to the causes we advocate for, as well as breaking down barriers of location, language and economic class.

The way we were able to connect through #MFIAfrica brought home the many struggles we share, and it was evident in the organic conversations we had in between plenaries that we had a lot of valuable information to share about organising in our contexts.

Visions of a connected future online

The systems of patriarchy, racism, ableism and capitalism are violent in that they cause ruptures between us. Through their manifestations – borders, financial disparities, domination through violence, barriers to access – as people from the continent, we have become disconnected from each other. We experience scarcity and distrust at high levels and because these systems are so powerful, these logics threaten to infiltrate how we organise. This is the same logic we must resist in fighting to undo these systems.

Unlike the systems of power which have created relationships of domination, the feminist way is to build a world where there is material equality and respect. The initiatives and values shared during the #MFIAfrica convening spoke directly to this. In common, we held the principles that accountability is key to remaining connected, that memory is political, and that it is imperative to expand our networks of care (online, offline, transnationally, as well as across cultures and generations). To this end, our creativity is central. Part of the gift of feminist thought is the opportunity to constantly rethink how things can be done differently; to be more just and more kind. This is an ethic that I think those of us at the convening are excited to take forward into all the different nodes we are plugged into, and to build upon.

- 8479 views

Add new comment