Image description: A man and a woman hold a solar panel on a roof. Image source: Zenzeleni Networks

Zenzeleni network is an entirely community-owned and -operated internet service provider in rural South Africa, with 65 hotspots, 1.2 terabytes of monthly traffic, and an average of 200 devices connecting per day. When researchers from the University of the Western Cape and local activists got together to start the network in 2012, the rural communities in South Africa’s Eastern Cape were isolated and marginalised by generations of systemic exclusion that left them without economic stability, electricity, reliable education or transport services, or internet connectivity. Like many of the nearly 4 billion people who remain unconnected to the internet today, these communities are hard to reach and economically ‘unviable’ for major network operators. In contexts like this, community networks – or, networks owned and run by local communities – present an opportunity to build communications systems tailored to local needs.

Like many of the nearly 4 billion people who remain unconnected to the internet today, these communities are hard to reach and economically ‘unviable’ for major network operators.

Zenzeleni (meaning ‘do it yourself’ in isiXhosa) has emerged as a pioneer among community networks in the global south and an exemplar of the unique challenges and remarkable successes of a cooperatively owned internet service provider. In this interview, Sol Luca de Tena, the acting CEO of the Zenzeleni non-for-profit company, discusses how the network developed its unique business model and the tensions inherent in connecting a local community to a global communications infrastructure. People like Sol are integral to the burgeoning ‘community network movement,’ which unites diverse local community network initiatives together, with the aim of sharing knowledge and advocating for better internet accessibility, including policy that accommodates these small local providers. Sol works to implement that agenda on the ground. Although many communities are rooted in isolating and often immobilizing local contexts, community network advocates like Sol are highly mobile – linguistically, educationally, and economically privileged to move between the local and global domains and bridge these different contexts. In addition to her role with Zenzeleni, Sol is also the vice-chair for the community networks special interest group of the Internet Society and part of the program committee of the Community Network Summit in Africa.

Kira Allmann: Since community networks develop to meet a specific local need for connectivity, people often seem to wind up joining community networks for diverse and personal reasons. It’s not always something they set out to do. How do you tell the story of how you came to be involved with the Zenzeleni network?

Sol Luca de Tena:

My background is in education and managing projects in technology innovation. So I’ve worked in different parts of the world, and I’ve lived in South Africa for 27 years, but I’m Spanish. When I lived in Europe, I worked in European-based large infrastructure technology development projects in renewable energy. And then I came back to South Africa, and I got involved again in innovation and renewables. There was a strong narrative about these programs being set up to enable social and economic development, but, you know, I kind of got more and more disheartened by the promise of big tech for socio-economic improvement. In reality, the people that need those problems solved most are left out of the equation completely. And that’s how I sort of gravitated more toward technology in communities and from communities themselves.

In reality, the people that need those problems solved most are left out of the equation completely. And that’s how I sort of gravitated more toward technology in communities and from communities themselves.

And then the link to Zenzeleni comes from a very personal place. I visited the village over 10 years ago because a very close person that I consider my brother moved into the community from Spain, and then years passed, and he died. And then one of the co-founders of Zenzeleni, who had known my brother, came to visit me once in Cape Town from the village, and as I got to know him, I became interested in this project he was working on, and they were at a point where they needed to develop the business model for this local network, and I started volunteering.

KA: So you were volunteering initially, but you slowly got more involved in developing the business model for the network?

SL: Yes. I was exploring what would make the network feasible, but there’s also something that has emerged from my increased engagement with peers in other community networks: how to build a business model where the success of a community network is intrinsically, symbiotically linked to the success or growth in a social and economic way of the community that you’re in. If the network grows, and the community remains the same in terms of its social and economic wellbeing, then you’re just turning into a big network operator. In Zenzeleni, the emphasis is that people own it, people care for it, and you need skills and understanding to be able to do that so that it keeps giving value to yourself and your community.

If the network grows, and the community remains the same in terms of its social and economic wellbeing, then you’re just turning into a big network operator.

KA: So what was the model that emerged from that exploratory process you engaged in?

SL: That’s a very good question, and I would say that we’re still defining it two years later. The premise of Zenzeleni is affordable communication that is quality communication in rural South Africa. And that’s been achieved, but there’s such a lack of stability in the economic situation of the area that you can’t put all of the weight of the costs onto that community because people won’t buy their 25-Rand top-ups systematically every 5th of the month, or whatever it may be, right? So the idea was also then to connect the local businesses or NGOs, schools, and clinics because they’re in a better position to pay monthly at a fixed rate, so we can predict cash flow a bit better, and that allows you to access the kind of bandwidth contracts that will make the entire network affordable for all.

The other aspect of the model required us to invest in skills development – skills in terms of business skills and management skills, which are very linked to people’s exposure to certain systems and languages. In this area, there is not much experience of systems, like transportation, working properly, so there was no existing experience of a trusted system that will just work for you, for your needs. You’re having to first define a company process that can actually be implemented and make sense to people and then try to bridge the reality that people live, creating something that is meaningful and valuable to them and connecting them to the systems that are already out there that they just have to interact with – like tax collection, or whatever it may be.

In this area, there is not much experience of systems, like transportation, working properly, so there was no existing experience of a trusted system that will just work for you, for your needs.

KA: Bridging seems important to your role. What is the relationship between the non-for-profit company and the local cooperatives? What are their different tasks?

SL: So one thing that came out of developing a business model for Zenzeleni was that we needed a sort of umbrella organization, which is the not-for-profit company (NPC) that is connected to the local cooperatives that operate in the villages. It became apparent that we needed certain critical skills like liaising with partners, including the government, to provide resources like funding, know-how, and infrastructure. However, the skills needed for advocacy and the access to where to advocate are so specialized that they’re very removed from the rural village setup. You know, talking to government is so removed from feeding your kids. Advocacy is a long-term investment that takes a lot of resources, a lot of fancy words in reports that really don’t solve your day-to-day life and issues. But it’s something I can do and have experience in.

For me, sitting at the NPC level, I do not presume to know how to manage, for instance, conflicts that the community experiences in their everyday lives. There are local and traditional methods for resolving conflicts that are more sophisticated than any business model I’ve ever seen. What I see from the NPC level is that we have the task of liaising with different partners like academia, government, or global NGOs to sustain the network locally. You need things like seed capital to start a local cooperative, and funders are much more confident to deal with people that have experience managing funds like that and have certain skills – language skills, for example. I can speak English, and I can pull out a CV with all this project management experience. So this multi-level setup has proved necessary.

KA: On a personal level, it seems like there are other kinds of bridging taking place in your role in Zenzeleni. For instance, you’re not from the local community in the Eastern Cape yourself, so how would you describe your relationship with the local community? What does it mean to be from outside the community, advocating for the local community initiative?

SL: So I think that from the onset, my biggest thing is that I try to be very aware that I am not from the community and therefore I need to listen. I need to listen very hard and sort of understand, to remind myself that to assume my own values and my own perspective would be forced. I don’t live here everyday. I come a lot, and I try to build my understanding from listening and from questioning. And I suppose the way that I am able somewhat to interpret what’s being said, or at least value how different the positions are, is that I have lived between two different worlds. I was born in Spain, I’ve lived in South Africa. I think from a very early age, I really understood how different perspectives could be, and how the natural order of things is just one perspective and not ‘the natural order of things.’ I try to speak Xhosa, the local language. I think you at least try if you respect the community. I want to understand their experience, rather than have them answer preconceived questions that I might have. I have some mechanical skills because the world is set up on a predominant narrative. So, a company has to look like this, and processes have to look like this, and success looks like that, and I come from that world, but I know that’s just mechanics. The predominant narrative doesn’t apply here.

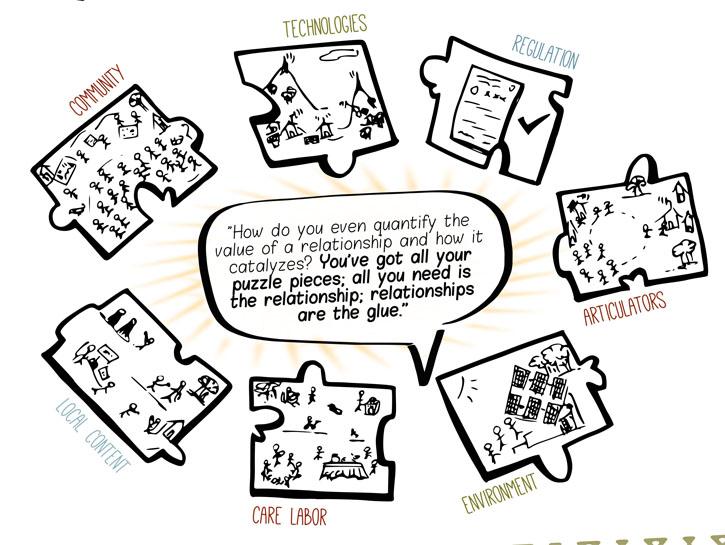

Image description: Illustration about community networks and relationships. Excerpt from Our Routes: Women's node - an illustrated journey of women in community networks by Bruna Zanolli.

KA: I wonder if you’ve thought much about what it is like to be a woman working in community network advocacy? This field tends to be very male-dominated because it’s a fairly technical undertaking. Building a network attracts people with backgrounds in telecommunications engineering, and they tend to be men.

SL: Yeah, I have thought of it, but mostly through kind of confrontation – of having to confront it. I think that in many of the conversations or the courses that are out there, or the write-ups about community networks, you know, what’s highlighted is usually the technical. And I don’t think there’s anywhere in the world, or any kind of organizational structure – but even more so in a community initiative – where the women are not pivotal. And yet, those roles are hidden.

We’ve just been through a major transition at Zenzeleni, and it was quite difficult for me, just sort of proving that what I was saying was valuable. I’ve often been the only woman in a board room or the only woman on a project, having worked in science and technology. And I feel that there are many things I do that could be done by other people. You know – the mechanical things, like check if someone's been paid, or send out an invoice, or even write up the justification for a project, or do cost control, or whatever it may be. But then there’s something else, and that something else is very difficult to articulate. It’s this care work. And that it’s not what I do, it’s how I do it. That what takes so much of my energy and makes me not sleep at night. I hold space. And through the confrontations of this transition that we’ve just passed through as an organization, it became more visible to me of how important the holding of the space, holding of a safe space, really is. It’s a space where people are OK, where the threat is left outside. I have two kids, and in a way, the best I could articulate it is it’s like holding a pregnancy or holding breastfeeding – it’s not the mechanical sense, there’s so much more to it. I find it hard to… it comes in pictures… I lack the words for it, and maybe that’s part of the issue. I think a lot of what women do isn’t usually spoken about or articulated.

I think a lot of what women do isn’t usually spoken about or articulated.

KA: In your experience, do you think this invisibility of women’s work exists at multiple levels in community networks?

SL: I have several different spaces where I do interact with women and men in community networks across the globe. And I have experienced it everywhere. In the last Community Network Summit in Africa, I was in the gender panel, and I felt like I shouldn’t be the one talking, so I decided to interview women from community networks briefly on their roles, and one of the things they explained to me was their daily routine.

You know, they get up, they clean the entire house, cook everyone’s breakfast, make sure the kids go to school, settle their husbands, and then walk two hours to get to the [community network] meeting, sit in the meeting, then leave the meeting to cook lunch for everybody, then come back to the meeting, are still expected to participate meaningfully in the meeting, and then they leave the meeting, walk another two hours, go back home, cook for everybody, sort out their kids, sort out their husband. And then, still, they were the ones in charge of charging the mobile phones using these charging stations that were [Zenzeleni’s] first business.

And when I asked more, like: Oh, but where were the men? They said: Oh, no they got tired. Oh no, they just had other things to do. And I thought: But didn’t you have other things to do? Of course they do. But they would get up three times at night to swap the phones. So you know what I mean? Like, you’ve only got three charges, so you wake up at night so that you can take the phones that are charged and put on the ones that need charging still. There was one incident right at the beginning of a battery being stolen, and one of the mamas actually slept with her battery from that point on. And that is such a huge task. If all those things don’t get done, then Zenzeleni would be nothing. It would be nothing. No matter what kind of devices, no matter what kind of business practice you develop, it would be nothing.

There was one incident right at the beginning of a battery being stolen, and one of the mamas actually slept with her battery from that point on. And that is such a huge task.

KA: We do often tend to privilege the technical over the social when it comes to talking about community networks. Gender dynamics might be one thing that gets overlooked. What exactly do you think we’re missing when we don’t focus enough on the social side of community networks?

SL: I think one of the biggest things is: why do we even start talking about community networks in terms of ‘what technology should I use?’ I get so many emails and calls and requests for recommendations, and they’re all about: What technology should we use? How can we access broadband? And I really think it’s kind of looking at it upside down. It should be: what do you want to do in your community? And then: ok, does it require a network? Or, what is your community’s strength or what is its drive toward doing something, and how can the community network serve that? Those questions are the ones that are going to determine what technology or business setup makes the most sense for you. I think it’s not just a question in community networks or rural setups. I think it’s across the board. In the biggest of summits, we tend to just think of the mechanics. And it’s like, well, the mechanics are there to serve a purpose. So what is the purpose? And I think that’s what’s left out.

KA: What do you think we can we learn about the internet and internet governance from these community networks then? It’s interesting that we don’t tend to ask big network operators these questions about purpose. It seems a little unfair that communities on the peripheries of connectivity need to ask this question. Or should I turn that around and say – actually, maybe we should all be asking this question about why we want connectivity, even those of us who are hyperconnected?

SL: Yeah, I mean, I would say that you’re right – we don’t demand those kinds of answers from a network operator, and that links to the kind of narrative that I was very much a part of in the renewable energy business. Why should a power plant be involved in socio-economic development? We’re just a power plant, and power equals development, right? But I think that community networks come out of a need -- there’s a gap. There’s a gap for access or affordability or even societal independence – you know – neutrality, or not being censored, or transparency, or a more politicized need. So their first birthplace is that. And yet then you jump to the tech, and that’s where we often end. You don’t go back to, you know, but why were we doing it in the first place?

There’s a gap for access or affordability or even societal independence – you know – neutrality, or not being censored, or transparency, or a more politicized need.

There’s a big social justice element to it for me. Community networks’ success and sustainability are intrinsically linked to the community’s social and economic success and sustainability. The health of one equals the health of the other. Because I mean, what’s the equivalent in a normal operator? The equivalent in a normal operator for me would be: are the shareholders getting their return on investment?

KA: But then it’s a very different set of priorities for the network operators. The goals of the network are to generate profit for shareholders. I think something people get excited about with community networks is that the community owns the network. What does community ownership actually mean in practice?

SL: Yes, that’s a very critical question from our perspective. So there are various levels to ownership. Practically, the cooperatives, which are the community-representing bodies, are the owners of all the assets of Zenzeleni. So 100% of the physical infrastructure is owned by the communities. They’re also the service providers. All the clients, whether they be individual users or businesses, pay the cooperative because they own the network. And in South Africa, it has a very specific meaning, which is about changing what the makeup of asset ownership and investment ownership looks like in order to reverse the inequalities of apartheid, where people in these areas were barred from owning anything. It is a challenge, and it does work into the power dynamics in the village. For the first time, maybe ever, it’s the black African community providing services to the white-owned businesses. And it’s not providing just any service, like, you know, cleaning. It’s providing a high-value service that makes or breaks the white business. In the historical context of South Africa, asset ownership was racialized. So in our case, it was very deliberate that the communities are communities that were previously barred from that right.

In the historical context of South Africa, asset ownership was racialized. So in our case, it was very deliberate that the communities are communities that were previously barred from that right.

But then there’s kind of a more spiritual, mental, emotional ownership. I think it’s just multi-layered. I think that people have a very strong sense of pride, especially the original cooperative members that have been in it for a while. I think that there’s a very clear sense of ‘yes, I am Zenzeleni.’ However, there is a tricky element when there are very highly technical questions. Like, we’ve just gone through a major milestone, which is defining agreements with customers. Before it was kind of on goodwill. This kind of formalization was required as the network really starts to grow, but they were very much like, ‘Oh no, you know best, you do it.’ So where’s that sense of ownership? When we say, for example, ‘we were in the Internet Governance Forum presenting this thing about community networks,’ it’s like – does the community own that?

KA: You’ve talked about many of empowering aspects of community networks but also the challenges inherent in striving toward social justice through network building. What motivates you to keep doing the work that you’re doing? Why are you staying committed to community networks as a solution for connecting the unconnected?

SL: What’s meaningful to me, and keeps me going in the face of much adversity, is really going back to my background, asking: what does innovation mean? Technology is this tool that always promises so much, but does it get implemented? I want to contribute to things that make sense to me, and social justice makes sense to me. Also, the right to safety, and by safety, I mean economic safety – being able to access a life that is OK. I don’t subscribe to many ideas of what a ‘good life’ is, so I won’t say, you know, that means having a car and a job. That’s not what I mean. Many people in South Africa suffer from malnutrition and various other threats that come from a poverty cycle, and I definitely feel responsible to contribute to addressing systemic issues. I think that community networks are a leading example of where technology is implemented from the impact up. Can we think about what the possibilities of impact can be first? Technology implementation should be close to the impact, close to where it matters. And the other thing is where the urgency lies – in the fourth industrial revolution. In the economic trend toward digitalized jobs or digitalized services, like health or education, community networks address a real urgent need within society. I understand community networks’ urgency in that it allows people to speak for themselves in their development.

I think that community networks are a leading example of where technology is implemented from the impact up. Can we think about what the possibilities of impact can be first?

- 7101 views

Add new comment