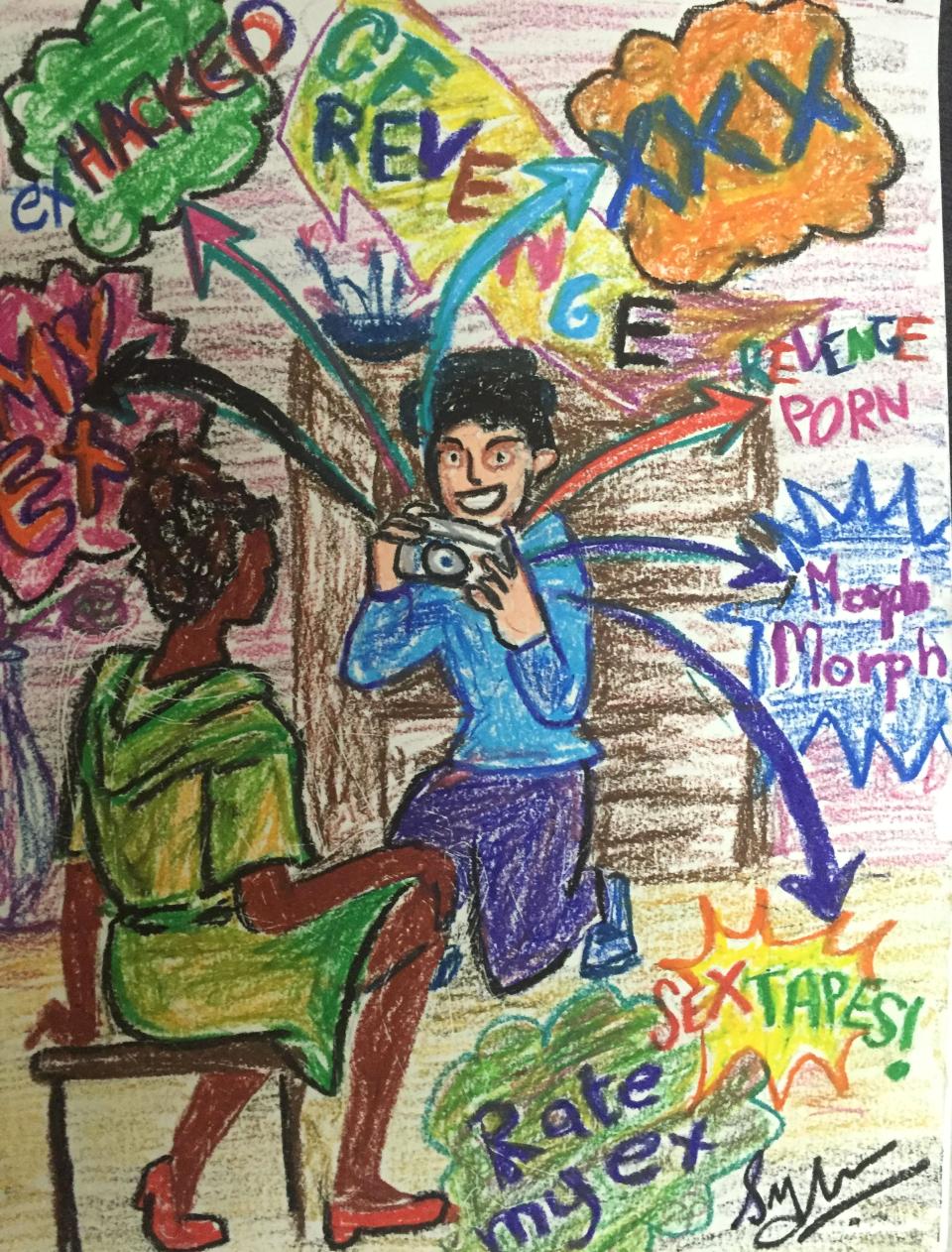

Illustration by Sylvia Karpagam

The internet has become and continues to be as much of a social phenomenon as it is a technological one. It has rapidly created novel virtual social spaces, and as a result is revolutionising human interaction. Platforms such as Facebook and Twitter have provided netizens with a forum to express themselves. The misuse of these platforms has however become rampant, as they have become fertile spaces for online violence against women – a factor that is proving to be a threat to women’s rights online.

A 2017 study by iHub, East Africa’s leading innovation space for technologists and digital activists, reported that incidences of online harassment against women namely:- doxxing, trolling, and cyber stalking, had become increasingly common. A similar survey by the Association of Media Women in Kenya (AMWIK) resonated with iHub’s findings. The survey titled ‘Online safety for women journalists’ (2017)’ revealed that Cyber bullying, trolling, defamation, sexual harassment and identity theft emerged as key digital threats facing women journalists in Kenya.

A 2017 study by iHub, East Africa’s leading innovation space for technologists and digital activists, reported that incidences of online harassment against women namely:- doxxing, trolling, and cyber stalking, had become increasingly common.

An earlier study by the Web Foundation (2015) revealed that 6 in 10 women aged 18-24 in Kenya, had experienced some form of online harassment. Globally, UN Women’s 2015 report findings unveiled that despite the lack of comprehensive data, it had been estimated that at least 23% of women had reported having experienced online abuse or harassment.

The ORIGINS of Non-Consensual Pornography IN KENYA

In the past few years, a uniquely modern and malicious form of online harassment has taken root in Kenya. This abuse – non-consensual pornography (most commonly referred to as “revenge porn”), has hit social media like a whirlwind, with groups such as “Mafisi Channel”, a notorious telegram platform operating solely for the purposes of sharing non-consensual intimate image among its 100,000+ members. The overarching aim of this channel is to shame and or bully ex lovers – predominantly women.

‘Non-consensual pornography is the distribution of sexually graphic photographs or videos without consent of the individual in the images. - The European Institute of Gender Equality.

Some aggrieved women have been bold enough to present their cases to relevant officers of the law charged with defending and protecting public security. One such case is that of Miss Kenya 2015 - Roshanara Ebrahim.

Miss Ebrahim was embroiled in a law suit after her ex boyfriend (Frank Zahiten), leaked her nude photos online, culminating in her being "dethroned" of the Miss Kenya title. Following this , Roshanara sued her ex boyfriend and the Miss Kenya organiser – Ashleys Kenya. A high court ruling delivered on December 7th 2016 ruled in favour of Roshanara, concluding that non consensual circulation of intimate images was a gross human rights issue, and that it breached the right to one’s privacy under Article 31 (c) of Kenya’s Constitution. The third respondent (Miss Kenya’s ex boyfriend), was required to pay the petitioner (Miss Kenya) 10,000$ in damages, for breach of her right to privacy.

A high court ruling delivered on December 7th 2016 ruled in favour of Roshanara.

Miss Roshanara’s case may be just one much-highlighted example of online and ICT-facilitated form of violence against women. There are a few other cases involving high profile individuals where either an ex-partner, and/or a hacker stole and distributed their private images on social media platforms, causing them immense damage and psychological distress, with some reportedly even contemplating suicide!

Still, it is believed that there could be more women reluctant to report these crimes to the relevant authorities owing to the stigma associated with these, that attaches to the women and not the men.

Illustration by Sylvia Karpagam

Measures being adopted to curb Non-Consensual Circulation of Intimate Images

There is steady progress thus far in efforts to deter this emerging problem. Kenya’s Computer Misuse and Cybercrime Bill (2018) for instance, criminalises Non-Consensual distribution of obscene or intimate images. Section 37 of this Bill states: ‘A Person who transfers, publishes, or disseminates, including making a digital depiction available for distribution or downloading through a telecommunications hardware or through any other means of transferring data on a computer, the intimate or obscene images of another person commits an offence and is liable, on conviction to a fine not exceeding 200,000 Kenya Shillings or imprisonment for a term not exceeding 2 years or both’.

It is widely believed that this will indeed immensely help curb the spiraling phenomenon.

At the global stage, in 2017, Facebook announced new Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools designed to keep non-consensual circulation of intimate images off its sites once flagged by users. This announcement came in the backdrop of Facebook holding a series of Women roundtables across the globe in 2016, whose aim was to discuss tech-related violence and solutions.

This announcement came in the backdrop of Facebook holding a series of Women roundtables across the globe in 2016, whose aim was to discuss tech-related violence and solutions.

Twitter similarly implemented a policy banning intimate photos or videos taken or distributed without the subject’s authorisation. A case in point – in July 2018, Cyprian Nyakundi, a renowned controversial blogger got his account suspended for going against the social media platform’s rules. This followed a move by the blogger to leak intimate photos of Radio Africa General Manager Martin Khafafa. In the photos, Khafafa – a married man, was pictured taking a shower with two ladies. It is believed that Khafafa flagged the account for Twitter’s prompt action.

On its part, the tech giant Google has measures in place too to take down requests in its search engine, that are related to non consensual sharing of intimate images.

Despite the above measures, some human rights activists feel that these efforts need to be adequately backed by remedies such as injunctions, civil law, and criminal law, to deter perpetrators from committing these heinous acts. On the other hand, some scholars who work on communication for development feel that a key step to combating online based violence is through sensitisation to alert internet users to what “revenge porn” entails, and the importance of Cybersafety, a sentiment that is echoed by iHub. ‘There is need to set in motion interventions to enhance policy reforms regarding cyber violence, build awareness and education, and form a network of relevant stakeholders committed to enhancing internet freedom of Women in Kenya’.- iHub Research

There is need to set in motion interventions to enhance policy reforms regarding Cyber violence, build awareness and education, and form a network of relevant stakeholders committed to enhancing internet freedom of Women in Kenya. - iHub Research

Conclusion

While the internet is largely perceived as a space to promote human rights, the rampant online violence may prove to be a challenge in the quest to protect these very rights.

In her address during the launch of the UN Women’s Report titled “Combating online Violence against Women and Girls: A Worldwide Wake-up Call”, UN Women Executive Director Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka decried online violence, stating that it had subverted the original positive promise of the internet’s freedom. Phumzile felt there was a need to take concerted steps to end it.

We need to respond and take heed of Mlambo-Ngcuka’s call and come up with legal and policy measures aimed at eradicating online gender-based violence against women. This will in turn help create a rich and enabling environment for achieving agenda 5 of the global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as well as Kenya’s Vision 2030 through the use of ICTs.

Director Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka decried online violence, stating that it had subverted the original positive promise of the internet’s freedom.

Footnotes

References

1. The European Institute of Gender Equality (Cyber Violence against women and girls - 2017)

2. iHub study- Enhancing Internet Freedom in Kenya (2017)

3. Association of Media Women in Kenya (AMWIK) Online safety for Women journalists’ survey (2017)

4. The Web Foundation – Women’s Rights Online: Translating Access into Empowerment (2015)

5. UN Women’s Report: Cyber Violence against Women and Girls: A Worldwide Wake-up Call (2015).

6. Kenya Law Reports Petition 361 of 201: Roshanara Ebrahim v Ashleys Kenya Ltd & 3 others (2016)

7. The Republic of Kenya’s Constitution (2010)

8. New York Times https://mobile.nytimes.com/2017/04/05/us/facebook-revenge-porn.html

9. The BBC http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-39502265

10. The Republic of Kenya Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Bill (2018)

11. Research ICT Africa (RIA) : The RIA Rap (Women @Facebook Roundtable: Discussing tech-related violence and solutions by African Women) - 2016

- 40209 views

Add new comment