On January 3, Caroline Sinders and I conducted a workshop at Tactical Tech about applying design-thinking approaches to understanding and addressing online and offline harassment. I write about the results of this workshop in two parts, the first, this one, dealing with the framing of online harassment in the context of speech, and why this needs to be reconsidered. The second documents how we applied a design-thinking approach to understanding how online and offline harassment occurs.

Harassment as a Speech Issue

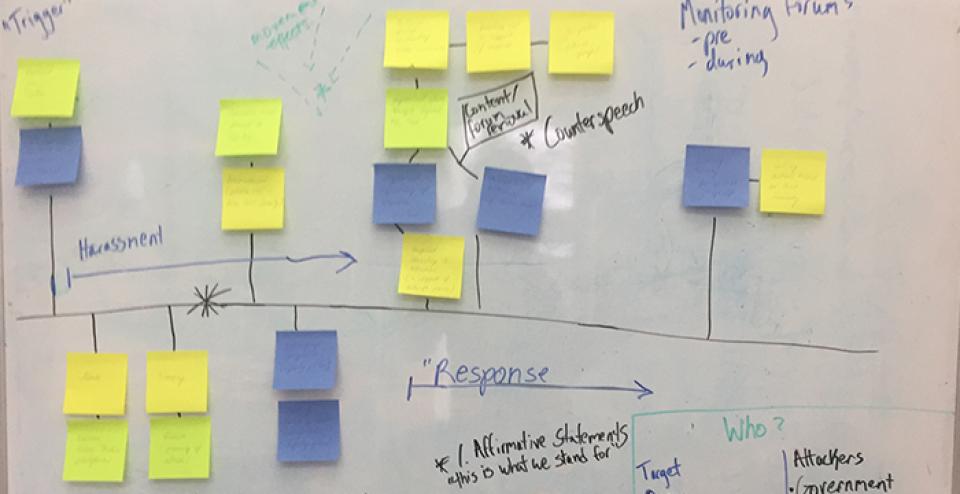

Caroline and I wanted to visualise and concretise the technical,cultural, social, and psychosocial elements of harassment; and to experiment with different methods to think about the problem.Why? Because approaching online harassment from the perspective of freedom of speech and human rights sets a specific frame on the problem and approaches solutions through the state and the law, even as the reach of these agencies are complex to establish in the governance of the internet.

If we want to think about minimising and controlling the impact and scale of harassment, then we perhaps need to think of it at a more granular level, as a socio-technical problem, and as something that is contextually constituted by the interactions of human behaviour, technical interfaces, and social context. We set out to map the problem of harassment from a forensic perspective, taking a transversal cut through the dimensions of how it happens and thinking about ways to represent it in system, and human terms.

If we want to think about minimising and controlling the impact and scale of harassment, then we perhaps need to think of it at a more granular level, as a socio-technical problem, and as something that is contextually constituted by the interactions of human behaviour, technical interfaces, and social context.

What’s the problem?

Over the past six months, Tactical Tech has been developing a project about online harassment in the context of a number of inter-linked political and social realities.

- There are a variety of words being used to describe phenomena associated with harassment – cyberstalking, bullying, hate speech, trolling – that sometimes involve serious behavioural, offline, technical, and psycho-social-emotional elements. Using certain kinds of language frame the problem in a particular way.

- Online harassment generally tends to be seen as a speech issue because everything that happens on the internet is thought of as speech. However, the kinds of harassment that take place through the internet have physical dimensions too, and go beyond just verbal abuse. Also, what does it mean to frame harassment as a speech issue when freedoms of speech and expression are typically framed to prevent censorship by states? How does the right to freedom of speech and expression get constructed, enacted and enforced when the primary threat does not come from the state, but from known people,or peers, co-workers? How does the liberal democratic cornerstone, freedom of speech, serve as a baseline where different social and political traditions of rights and agency exist? We believe these are important questions if we have to be more creative and effective in addressing the problem in its various, global, manifestations. Sky Croeser’ recent article that teases out the tension that has developed in framing online harassment in terms of freedom of speech has been a valuable inspiration in trying to think about the possibility of different approaches to contending with the manifestations of online harassment in a range of contexts.

- The other political reality we consider is around how regulation and accountability in the online world is possible, or not, with offline laws, ideas of rights, and policies. It is difficult to make online ‘violations’ (everything from ‘piracy’, to the severe penalties faced by hacktivists, to privacy) accountable through offline laws. In some countries, feminist activists like the Digital Rights Foundation in Pakistan, and the advocacy group Feminism in India, are working with law enforcement to address online harassment and violations and make them accountable through traditional legal structures. Others elsewhere may expect accountability through social media platforms.

We approach this constellation of problems from a design-thinking perspective, to take it apart and reconstruct it – rather than trying to think “through” it – as if blasting a tunnel through a mountain. What else is harassment if not just a violation of the right to speech?

What else is harassment if not just a violation of the right to speech?

Who was in the room

The workshop was early in the year when most people are still on holiday, or in hibernation mode if they live in Northern Europe or North America; so we didn’t expect a strong response from our invitees. We were a group of ten people from diverse backgrounds – privacy advocates,technologists, computer scientists, designers, researchers, and writers. Participants were of varying genders, nationalities and ages and lived in Berlin, New York, or San Francisco.

What do we talk about when we talk about …

Taking inspiration from Donna Haraway who says, “it matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts what descriptions describe descriptions…” it was important for us to start with a baseline of where each of us come from in how we frame and think about online harassment through language.

Donna Harraway says – “it matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts what descriptions describe descriptions…”

We did a short exercise for the group to claim words that they feel appropriately describe the reality of online harassment, and words they find problematic. This resulted in a rich discussion in which some important themes emerged; the first related to how thinking about ‘harassment’ in terms of speech was considered problematic; and second, that words like ‘trolling’, or that harassment is “only virtual” are still far too commonly used.

Words that were considered more appropriate and palatable were: attacking, bullying, online harassment, abuse, contextual violence, targeted abuse, targeted retaliation, silencing, trauma. One cluster of problematic words honed in on the tension with notions of speech:

“Inevitable result of ‘free speech‘”

“Freedom of speech”

“Constitution”

“Hate speech”

Each of these words are significantly different although they are held together by a common idea that equating online harassment with ‘speech’ is problematic. In the discussion that followed, participants clarified that on one end is the idea that some harassment is enabled by the very fact of people being protected by freedom of speech laws; and on the other, that wrongly applied ideas of speech – such as hate speech – have come to embody what online harassment is, when it clearly isn’t a matter of speech alone but includes offline repercussions, or instills fear for physical safety. Moreover ‘‘hate speech‘ is, in a legal sense applied to expressions that may be construed as an incitement to violence against groups, rather than individuals, based on race, ethnicity, nationality, or religion.

The workshop group talked about how the freedom of speech that the internet is thought to enable emerged from a specific milieu- mostly White male Californian Cyber-libertarian-ism of the 1990s – that ended up shaping early impressions and practices of the internet. The idea that “information just wants to be free” perhaps pre-supposes that creators of that information already have the experience of human rights and privilege, which could be said early adopters of the internet enjoyed. One participant referenced recent re-readings, or appropriations of John Perry Barlow’s Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace, which seemed woefully limited now.

The idea that “information just wants to be free” perhaps pre-supposes that creators of that information already have the experience of human rights and privilege, which could be said early adopters of the internet enjoyed.

‘Freedom of speech’ is a legal concept that ensures that the state does not limit citizens’ voices and expressions; in the Western, liberal democratic tradition it has served as a cornerstone of democracy. As Croeser notes, it does not necessarily port over automatically to social media platforms that are not the same entities as public spheres although they may be treated and shaped as such.

“We need an internet version of ‘don’t shout fire in a theatre‘” said one participant echoing a commonly held feeling in the room that we were dissatisfied with the extrapolation of freedom of speech as a legal right and conceptual framing to address online harassment. We need to consider some thing else.

“We need an internet version of ‘don’t shout fire in a theatre‘” said one participant echoing a commonly held feeling in the room that we were dissatisfied with the extrapolation of freedom of speech as a legal right and conceptual framing to address online harassment.

There was also resistance to the use of the word ‘trolling’ as well to refer to the entire phenomenon. ‘Trolling’ has a specific history of use as well and what was first a behaviour has now become both identity and Bat signal, as Whitney Philips writes. Trolling survived the early years of the internet whereas other subcultures and practices have not, such as ‘flame wars’, ‘blatherers’ and so on, but it is perhaps a limited word, too, said the group.

It was valuable to have another spoken language perspective in the room (and we discussed the importance of doing this exercise in other languages so as to understand how the issue is being framed in local contexts). One participant was a German-speaker who has dealt with harassment and attacks and is a feminist activist. She referred to the cluster of words that minimize online attacks as just being about the virtual, that cybergewalt (cyberviolence) is considered to be just virtual with no offline repercussions.

Recent work by Ingrid Burrington, Andrew Blum, James Bridle, Trevor Paglen and others on infrastructures of the internet also serve to complexify the debate over regulation of speech online i.e. to make it more complex and layered. Uncovering the materiality of the internet throws into question where particular regulatory frameworks or social contracts of the internet come from. If the internet is not a free speech soapbox but is a complex assembly of material, political, economic, symbolic and imaginary interests and power, then how does a specific idea of free speech become it reigning social contract?

There are, also, many diverse traditions of speech, regulation, rights, expression, participation and mobility from around the world. What are they, Sky Croeser asks (personal communication, January 11, 2017) and how do we draw them out? What other practices of community, speech and anonymity exist in online spaces and how can we amplify our learnings from them? This is work we believe should receive more attention, and particularly from online spaces that use and test them. We believe this is work that deserves more attention, and will look forward to Sky’s new writing on this topic, as well as responses to it.

Next, the second part of this two-part post will describe the workshop we did and its results.

What other practices of community, speech and anonymity exist in online spaces and how can we amplify our learnings from them? This is work we believe should receive more attention, and particularly from online spaces that use and test them.

Footnotes

Haraway, D. (2016) Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin

in the Chthulucene (Experimental Futures). Duke University.

- 8182 views

Add new comment