Important achievements were attained at the recent Commission on the Status of Women 57th session reviewing government progress worldwide in addressing violence against women and girls. One such attainment was governments’ recognition of the growing role of information and communication technologies in the continuum of violence against women.

Perhaps you are a bit skeptical about the usefulness of such declarations in transforming women’s every day lives. After all, in this same meeting feminists and governments alike heard about ever-increasing violence against women and girls – sexual violence in areas of conflict, sexual harassment on the streets, adolescent and child pregnancy, intimate partner violence, feminicides. Even if we interpret greater documentation as a sign of government progress to address VAWG (despite many noted limitations in unifying and honing data collection) the figures are numbing. We still need those vital civil society shadow report statistics to offer us a closer and frequently harsher, albeit unoffical, view of VAWG realities across the world.

So, is there any point to these yearly reviews and declarations? A recent, much smaller gathering on feminicides in Mexico City – made available to us all thanks to the wonders of ICT (1) – gave me a different perspective in a country whose name has become a synonym for words like “feminicide” and “impunity”.

Establishing the concept of feminicides in Mexico has been part of a journey using the law as a mechanism for change. Feminicide violence is clearly defined as being rooted in discrimination, which the State is under obligation to eliminate. (Mexico long ago signed the Covention for the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination). The landmark findings of the Interamerican Court case on Campo Algodonero make the Mexican government legally and judicially responsible because, indeed, it had signed the accords of Belem do Para – Mexico had argued that such signed accords weren’t binding. Such are the slow-growing fruits of two incredibly meaningful declarations, in addressing the most extreme expression of violence against women. Sadly, however, you rightly note – Mexico’s feminicides keep growing. The National Citizen Feminicide Observatory (OCNF for its initials in Spanish) has documented 4,112 feminicides in just 13 states from January 2007 to June 2012 (2).

OCNF’s networked efforts to build evidence and track recourse are the grimmest testament to mexican impunity, especially noting the institutional violence in feminicide cases which are not properly investigated and are dismissed as a result of organised crime. Therefore the Observatory has focussed on how to end impunity. Their answer? Make sure that feminicides are tipified in state law, to recognise them for what they are and what they are NOT: “crimes of passion”. And ensure that there are specific investigative protocols to address them. Not hundred-page protocols like those that were copy-pasted from international accords with no understanding of local realities where “CSI” units might not even have a camera to take photographic evidence at the scene. No, the national observatory has boiled it down to a simple, practical recommendations to ensure the procuration of justice. Such principles include – treat all violent deaths of women as feminicides until you find evidence to the contrary. For example, question suicides, especially when women’s bodies show evidence of bruising and torture. Don’t invoke gender stereotypes when you assess the crime. Don’t criminalise family members – their daughter’s death is not due to them letting her come home from work late at night. Explore evidence before assigning justification- if you are convinced the feminicide was “due to organised crime” you can be blinded to other evidence.

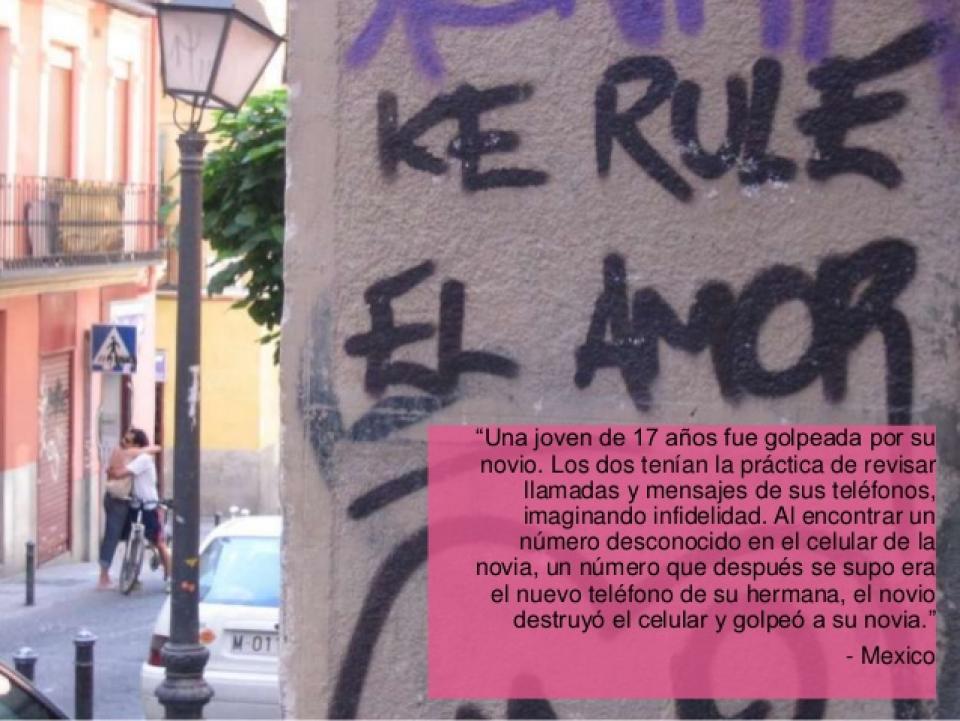

Call sheets, noted OCNF’s Yuriria Rodríguez, are vital sources for understanding victims’ last communications. The assignation of feminicide in one case in Sonora had been cast aside, citing “family reasons” behind the woman’s murder. Rodríguez noted that on the day of her death the victim had received over 100 calls from the same number, from one of the suspects in the case. If the role of technology in the continuum of violence is taken seriously, not only would call records become a regular part of investigations, violence mediated by technology might be taken more seriously by authorities, women may recognise warning signs earlier on, and intervention before violence escalates may be possible. But first, like the Observatory, it all starts with evidence building, and declarations, and legislation, and protocols.

Which is what this issue of GenderIT.org is all about. You’ll find information around evidence-building and finding solutions for recourse around VAWG mediated by technology in Colombia, the Philippines and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In Mexico, we are proud of our “Ley general de acceso de las mujeres a una vida libre de violencia” – the general law for women’s access to a violence-free life”. Feminists purposefully fought for the law to be framed in the positive. It is a mouthful to say and cite, but each time it is, we are reminded that it is indeed our right to live free from violence. It’s there, signed into law, in Mexico’s attempt to put international conventions into practice on the ground. The challenge now is making the law reality. But you do have the right.

You do have the right to live a life free of violence. Yes. You. Do.

Footnotes

(1) “Feministas Socialistas: Feminicidio” featuring, among others, Andrea Medina and Yuriria Rodríguez as speakers. www.youtube.com/watch?v=pEZpmtzg_qY, www.youtube.com/watch?v=6eCTds8sbao

(2) Joint report presented by Mexican civil society organisations for the second round of the Universal Periodic Review of Mexico.

- 17489 views

Add new comment