Image credit: Go: Woman considers a play. By Chad Miller. Creative Commons BY SA. Via Wikimedia Commons.

It's been nearly a decade since research stirred the quiet world of Wikipedia editors with a revelation: there is a gender gap among Wikipedia editors. Only between 15% and 10% of Wikipedia editors are women.

In statistical terms the situation has remained pretty much the same since, despite various commitments made by the Wikimedia Foundation (which supports Wikipedia and all associated projects).

But are we, women who are actively part of the Wikimedia movement, in the same situation we were a few years ago? What has changed and what still needs to be done? Throughout this article and the two that will follow, my invitation is to think about how far we women have come on Wikipedia and how we can continue to generate an inclusive environment that allows us to grow.

But are we, women who are actively part of the Wikimedia movement, in the same situation we were a few years ago? What has changed and what still needs to be done?

Don’t see the forest for the trees

A few weeks ago, a Spanish newspaper asked, "Why is Wikipedia still man's territory?". The article commented on recent research published this year by the Open University of Catalonia (UOC) based on data from 2017.

The research took only software-measurable variables, such as user gender profiles and article classification categories, to determine the low participation of women on Wikipedia. However, this type of research often takes a snapshot with what can be measured exclusively on the platform. This ignores the role that women play in other spaces of the Wikimedia community and in the movement, and does not reflect its diversity.

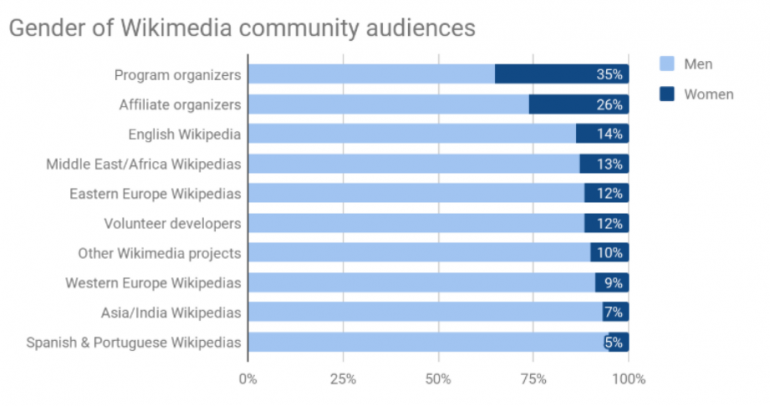

For example, the Community Insights report produced in 2018 by the Wikimedia Foundation showed that women had almost 35% participation in movement activities and 26% in affiliated organizations.

Graphic by EGalvez (WMF) under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence. Bar chart showing the gender distribution of participants in Wikimedia communities. Women reach their highest participation (35%) as programme organisers.

This is not to say that these numbers are necessarily good, or that criticism around women's participation on Wikipedia should be silenced. But the problem with a snapshot based on what the platform says is that it helps reinforce gender stereotypes and renders invisible the work of women who are already in the movement.

This emulates the problems often seen in the free software movement’s commitment to Linus Torvalds' phrase: "show me the code", with the idea that the only way of relevant participation in the free software world was through writing code. Taking data that comes exclusively from the software (from the Wikipedia platform) crystallizes the idea that the only contributions that count are the edits, the contributions made online. This ignores the fact that in the adventure of building collaborative knowledge there are many other equally relevant tasks.

Taking data that comes exclusively from the software (from the Wikipedia platform) crystallizes the idea that the only contributions that count are the edits, the contributions made online.

Getting organized is the task

Indeed, it is not enough to be on the platform and edit. And many women in the movement quickly realised that when they analysed the phenomenon of the gender gap. It was necessary to organize, establish alliances and invite and teach other women and identities to edit. That's what the 35% of women in the "program organisers" category and the 26% of "affiliated organizations" responded to.

These women are the ones who have organised Wikiprojects and organizations such as Art+Feminism, WikiWomenInRed, 500 Women in Scientists, Wikidonne or Wikimujeres, to name just a few. They are the ones behind the collaborations and support networks found in Telegram groups to intervene in on-wiki discussions and build mutual support when some editor or admin make arbitrary decisions. It has been the work of these groups and the LGBTQI++ minorities and other marginalised groups that has garnered a commitment from the Wikimedia Foundation to support volunteers who identify within the LGBTQI++ community. And, just as importantly, it has been these women's and minority groups who organised, demanded and secured a Universal Code of Conduct, which will help change many of the harmful interactions within the platform that prevent participation of women.

It has been these women's and minority groups who organised, demanded and secured a Universal Code of Conduct, which will help change many of the harmful interactions within the platform that prevent participation of women.

Many of these women are also active Wikipedia users and editors, but is it fair to judge their contributions based solely on the number of edits? On whether or not they declare gender on their user profile? (They may have good reasons for not wanting to do so).

On Wikipedia, the tasks of organising, of building alliances, of training female editors, of inviting new people to join, are the equivalent of housework. No one takes it into account. But housework and organising are not a given. It is not by chance that an important part of those who do these tasks are women. But this hard, overlooked and under-supported work is necessary to build a more inclusive environment.

For a Wikipedia where we all fit

It is useful to have statistics on the actual participation of women on Wikipedia, and no one wants inflated statistics. In fact, many of these metrics are useful for assessing progress and investing more effort. But the decision about what data counts is as political a decision as any other.

The way these data found their way into the publishing media is not innocent either. Thus, for example, some of the articles that the UOC research collected were titled: "The story is still told by man", "Wikipedia is still a man's territory". The idea implicit in these verbal constructions is temporal continuity: nothing has changed with respect to the past, everything remains the same, men continue to win, and as the efforts have not been worthwhile, it will continue to be so. Don't even try, ladies.

The decision about what data counts is as political a decision as any other.

Of course, those who research on Wikipedia in general do not control how the media communicate their research. But it is also important to understand that the media, particularly Spanish-speaking media, has found some morbidity in communicating these percentages. Good news is not news, so do not miss the opportunity to publish a story that talks about how bad Wikipedia is, as if the gender gap or the glass ceiling were not phenomena that also affect, incidentally, newspaper editors and universities. Anna Torres already said it: with a sexist society, we have a sexist Wikipedia.

Since the gender gap statistics became known, women and minority and dissident communities have achieved many victories within and outside the Wikimedia movement. We have done so navigating a complex community and context, with multiple conflicting interests, and are often unsupported or in outright opposition to the consensus controlling community. Building collaborative knowledge is much more than participating in a software platform. It is time to recognise the value of these other tasks.

- 6232 views

Add new comment