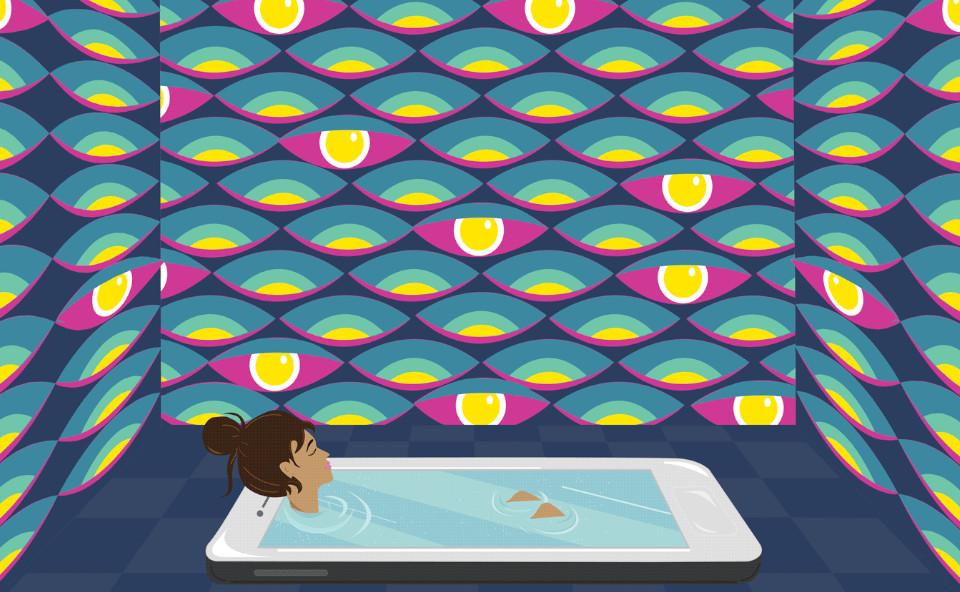

"Being Watched" by Meshi Sanker on Behance. Creative Commons BY NC-SA.

Monitoring and Control

The reduction and dehumanisation of women have come to validate practices that threaten our autonomous expression of personhood through the violent control and subjection of women’s bodies. Women find their life stories hijacked by sexist narratives that forcefully promote ideas of who women should be rather than who we are.Msimang, S. (2021). Surfacing: On being black and feminist in South Africa. In Winnie Mandela and the Archive: Reflections on Feminist Biography (p. 17). Wits University Press. Similarly, surveillance uses such hegemonic norms and narratives to design multiple separations of people into normal/abnormal, good/evil’ etc.Foucault, M., & Sheridan, A. (1995). Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison [E-book]. Vintage Books. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/55026/discipline-and-punish-by… Hence legitimising control and power over people's lives and bodies. Meanwhile, in the attempted segmentation, people face violence for defaulting against set standards, thus facing disciplinary action, which currently includes Online Gender-Based Violence (OGBV).

OGBV, i.e. violence facilitated through technology by one or more people harming others based on their sexual or gender identity, includes stalking, bullying, sexual harassment, defamation, hate speech, or other online controlling behaviour.Iyer, N., Nyamwire, B., & Nabulega, S. (2020, August). Alternate Realities, Alternate Internets : African Feminist Research for a feminist internet. Pollicy.org. https://ogbv.pollicy.org/report.pdf Here, women are bullied and targeted for embodying identities especially deemed as non-conforming to normative gender ideals, embracing their visibility or simply existing within the space. Surveillance takes away power from people by reducing and demarcating them into ‘useful’ and ‘ intelligible’ categories that seek to subjugate and rearrange people into a political practice. It confirms the entitlement to women’s lives and bodies as everyone’s business and property. This entitlement helps us understand that the harassment women face online echoes patriarchal enforcement of submission and punishment,Gqola, P. D. (2015). Rape: A South African Nightmare (1st ed.). Melinda Ferguson Books. one that operates within disciplinary domains of oppression.

Women are bullied and targeted for embodying identities especially deemed as non-conforming to normative gender ideals, embracing their visibility or simply existing within the space.

While these instances may speak to how offline social paradigms are mirrored online, it is also necessary to understand how social media design, especially visual-based media, may play a role in how Muslim Women's interactions are surveilled. Given the fundamental understanding of cultures that codify online surveillance, what does it mean for a supposed ‘neutral’ space to facilitate the disciplinary power of the gaze that is fixed everywhere?

Being a visible Muslim woman: the experience of a Muslim influencer

“Instagram puts forward a certain aesthetic of a Muslim woman”, Fatou, an African influencer shares. The aesthetic of a Muslim woman promoted by Instagram influences their monitoring experiences and how they are perceived. Suppose the widespread image of a Muslim woman influencer is a non-black African Muslim woman. In that case, spaces such as Instagram also promote the monolithic narrative of who Muslim Women should embody while sidelining black African women in the space. This forces the need to assimilate into that which “works”. Hence, given Fatou’s and other African Muslim influencers complex experiences on Instagram, most attempt to balance between ideals that expect them to replicate the Instagram version of a hijabi while staying authentic to her personal identity as they curate their online profile. These concerns show a first-hand account of how Instagram facilitates the performance of the aspirational version of ourselves.

Black women celebrities are portrayed as “always ready to be gazed upon”,Dubrofsky, R., & Amielle Aagnet, S. (2015). Feminist Surveillance Studies (2015–06-12). Duke University Press Books. and this is also true for influencers. Similarly, Fatou explained that people who monitor and bully do so because they believe they have the ‘right’ or freedom of speech to give their opinions on anything available to them. The intricacy of this situation is that while the women may not have full agency on how their content is responded to or participate in their objectification, visual media present them as having 'autonomy' and authenticity.

Instagram recently explained that content on the “feed” and “stories” appear in an order of “what one cares about”, where they referred to such content as close friends and acquaintances. Here, algorithmic decisions determine what content is seen or unseen and which ones become viral or not. In this scenario, if the algorithmic-determined standard of a Muslim woman is a specific kind of feminine and modest creator, then such an aesthetic becomes the focal standard. At the same time, “what people care about” does not translate into positive neutrality. A serial aggressor whose goal is to target Muslim influencers would be considered to “care” about their content given that they are constantly and specifically engaging with influencer’s content and activities online. The issue presented in this case shows yet another example of how surveillance abstracts from context. Algorithms cannot fully determine who a close acquaintance is or whether a particular user wants their close family or friends to view their content online.

The aesthetic of a Muslim woman promoted by Instagram influences their monitoring experiences and how they are perceived. Suppose the widespread image of a Muslim woman influencer is a non-black African Muslim woman.

On the other hand, black Muslim women face what Mona Eltahawy describes as the trifecta of oppression (misogyny for being women, racism for being black and Islamophobia for being Muslim). To be visibly Muslim online means to be caught between multiple expectations and realities where people expect one to represent the Instagram aesthetic of a hijabi while censoring oneself from the “haram police” who watch and control Muslim women’s activities within an Islamophobic community. Harassment on visual-based social media differs from Twitter or Facebook, where content gains traction to other communities through shares and retweets. On Instagram, for instance, a few influencers shared that targeted bullying happens in isolation because of the platform’s focal functionality being pictures and visuals. As such, it reduces how much others witness targeted bullying of Muslim influencers, especially when their will read long captions is minimal.

Furthermore, due to this design, aggressors often utilise direct messages (DM), therefore, the isolated experiences women face. The isolation on Instagram diminishes the chances of solidarity with victims of abuse. It also makes use of a panoptic strategy of immobilization, individualisation and partitioning. Panopticism abolishes collectives by replacing them with separated individualities.[2]

Consequently, while Fatou feels monitored by different groups of people who go ahead to message her because of the content she posts, unapprovingly, her self-censorship is primarily due to the ‘criticism’ (read bullying) experiences Fatou has heard other Muslim women endure. Thus, her reasons to precautiously avoid being a target of harassment and people who might message Fatou telling her “a Muslim woman should not do that”.

Influencers on Instagram are considered as prosumers (content producers and consumers) seen to have “put themselves out there” as agents of a masculine cybergaze. [5] Social media is indeed a source of pleasure and monetary gains for many influencers. By promoting her content on Instagram, Fatou was able to gain visibility for herself and her podcast. Many other influencers also curate content based on their love for fashion, writing and awareness creation, to name a few.

However, if most women have to constantly rethink or overthink what they post on social media given the existence of violent cybergazes, then their expression of pleasure through what might be considered agency becomes complicated and threatened.

The Digital Panopticon

Social media monitoring, Kovacs theorises, makes us carefully construct our online identities, and only a few people are immune to the disciplinary power of the collective cybergaze. What one might consider the simple act of posting a picture invokes a self-monitoring and overthinking process. Hence, the cybergaze embodies disciplinary power that scrutinises others, classified as part of interpersonal domains of oppression. In this realm, individuals arm themselves with the role of policing, enforcing, and punishing others through everyday interactions. In addition, other forms of power, such as the state, lie behind the cybergaze to organise violence and discipline those who default from norms, allowing the control of women's expression and autonomy online. On Instagram, when people are on display, communities of people play the "policing" role, punished through violence online and offline.

Panopticism is the systematic design of monitoring cultures. For surveillance to be effective, it must be embedded within our hegemonies and through technological structures. Surveillance in our hegemonies operates as a way to demarcate, break down and produce governed bodies through political anatomies of surveillance.

Surveillance is organised through the gaze of the community as well as large databases and sophisticated technology to control and ensure that people conform to the norms and standards. However, at the core of the panopticon is people, that is, the design of a prison-like structure that leverages hypervisibility where people know they are being watched but cannot tell by who or how. Anyone can wield the panoptic machine to administer the power of surveillance, and a panopticon represents more than a building but a power tool. However, the digital panopticon unifies both human and non-human surveillance through the fundamental structure of how algorithms work. The unification of both types of surveillance is organised through tech companies’ use of surveillance mechanisms to gather information on users to predict future behaviours through machine learning that finds patterns in large amounts of data, thus the first stage of the panoptic structure. Meanwhile, the continuous interaction with posts online by different users who are shown specific content based on what social media companies claim the user “cares” about reinforces community surveillance, which generates such amounts of data, thus feeding the algorithm.

Social media spaces, especially visual-based media such as Instagram, or TikTok, facilitate this type of digital monitoring. In both spaces, people’s lives are on display, by design and by pleasure. This also influences the type of curation that happens within the space. In a recent interview with Somali creatives, Najma uncovers that “we tend to play a role in our monitoring by constantly updating our profiles and stories on where we are and what we are doing”. Meanwhile, Instagram also facilitates a digital panopticon through what Fatou explains as the unfair dynamics of the platform allowing people with no profile picture, real names, or content to have full access to you. This scenario she shared also went as far as people stalking her offline. The profit-based value of big tech platforms leverages influencer's culture and hypervisibility to achieve its goal. Social media algorithms can determine many things about a person based on the kind of influencers they engage with. The same can be said for the traction visual media platforms such as Instagram, Youtube, and TikTok have gained from influencer culture. Hence, part of the profit motive pushes followership and engagement as financially lucrative for the influencers, consequently discouraging the will to carefully create a safe community even when many are stalkers and aggressors.

Part of the profit motive pushes followership and engagement as financially lucrative for the influencers, consequently discouraging the will to carefully create a safe community even when many are stalkers and aggressors.

At the same time, surveillance through panopticism influences the need to assimilate. It causes a permanent state of visibility to the unknown that it becomes a more straightforward tactic to fit in. Assimilation as a way to avoid monitoring achieves the panopticon’s goal that makes people self-monitor and control themselves. Thus, women such as Fatou claim to have witnessed the bullying of other women, and the extremes of stalking begin to “carefully” curate themselves online to keep away from being targets.

The digital panopticon operates through a sexist, misogynistic and Islamophobic lens, which takes away any supposed neutrality. Similarly, by promoting a singular image of who a Muslim woman should be or look like, Instagram affords a carefully designed visibility of a panopticon that flourishes from controlling people’s bodies. At the same time, carefully curating oneself to avoid bullying or harassment from known and unknown gazes is the core function of panopticism - where power remains visible yet unverified. [2]

The digital panopticon operates through a sexist, misogynistic and Islamophobic lens, which takes away any supposed neutrality.

Subverting the gaze

Fatou’s horrific stalking experience was partly a result of her openly sharing her activities online. Yet, as Instagram's policies, moderation and algorithm continue to put Muslim women at risk, the women work through strategies to protect themselves.

Women like Fatou shared that they reported their incidences; however, Instagram’s action was not effective. They explained that “a post is gone” and not the aggressor. Fatou put her account on private to view who follows her. Still, she expressed that her strategy is easier when you have a small number of followers - which is not the case for influencers. Similarly, it does not stop an “anonymous kitten” from following you and having access to parts of you, thus contributing to the discomfort of the monitoring gaze of the unknown.

Additionally, Fatou said other influencer friends blur their faces online to avoid being targeted offline. No one wants to be a subject of harassment or scapegoated as an example to others. Yet the attempts to subvert the cybergaze continues to prove insufficient as the space becomes increasingly violent to women and queer people.

Thus far, I have tried to explain how surveillance is the structural domain of oppression that causes disciplinary action of online gender-based violence. Mere images or videos of people cannot provide a contextual understanding of their lives and social cultures. For instance, the two Egyptian TikTok influencers recently sentenced to 10 years in prison for defying "family values" over content posted on TikTok and other social media channels explained that their content was taken out of context. Most influencers also shared how they were forced to rethink certain activities they enjoyed because they might receive unsolicited DMs and comments from the haram police. Consequently, surveillance abstracts people from their contexts and creates disembodiment as women attempt to escape the gaze.

Surveillance abstracts people from their contexts and creates disembodiment as women attempt to escape the gaze.

The notion of agency becomes marred in instances of abuse and control. Hence, it becomes necessary to investigate the offline gendered structures that validate control of women’s bodies and locate the role of social media moderation and design in the monitoring experiences of black Muslim women influencers.

- 2670 views

Add new comment