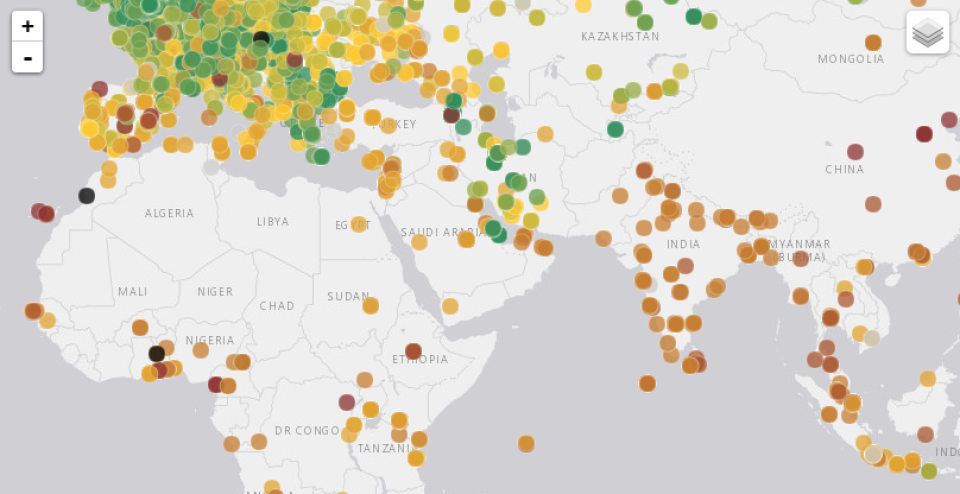

Atlas showing internet penetration based on standard ping measurements. Original at Ripe Atlas

Targeting ‘the gap’ between women and men in access to the internet is fundamental in reaching the goal of access for all. In an article for the Alliance for Affordable internet, the Web Foundation argues that the indicator of this gap should be calculated relative to a women-centred reference when the intention is to focus on the disparity and disadvantages faced by women.

The indicator of this gap should be calculated relative to a women-centred reference when the intention is to focus on the disparity and disadvantages faced by women.

Gender internet access gap indicators contribute to defining goals for international and country-level policies. They intend to convey the relationship between female and male access, and account for different countries’ total internet penetration, and male and female overall populations. Consider, for instance, values indicated in the Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) 2018 Inclusive Internet report, which uses women-centred references. South Africa and Kenya both have slightly more females in their total population and higher internet penetration than the rest of the continent, at 52% and 44% respectively. However, while the gender access gap in South Africa is just 2% difference, in Kenya it is 54% difference. Meanwhile, for countries with lower internet penetrations like Namibia, at 16%, and Cote d’Ivoire, at 22%, there can be widely different gender access gaps. Namibia is the only African country with a gender access gap in favour of women, at -7%, but also has a much higher overall population of females; while Cote d’Ivoire has a much higher overall male population and a gender access gap of 60%.

South Africa and Kenya both have slightly more females in their total population and higher internet penetration than the rest of the continent, at 52% and 44% respectively. However, while the gender access gap in South Africa is just 2% difference, in Kenya it is 54% difference.

International Telecommunications Union (ITU) and the Groupe Spécial Mobile Association (GSMA) show that internet user gender gaps in the past few years have narrowed in ‘developed’ regions. Unlike Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) and the Web Foundation, however, ITU and GSMA calculate the value of the gender gap as proportions of the internet penetration rates for men; that is, the indicator is the difference in the internet penetration rate between men and women as a proportion of the internet penetration rate for men. Use of a male-centred or women-centred ratios contribute to markedly different values. For instance, ITU published a gender gap of 25.3% difference for the entire African continent using a men-centred reference in 2017; yet, if the same proportions are used to calculate relative to women, the gender gap is 33.9% difference.

Use of a male-centred or women-centred ratios contribute to markedly different values.

Both gender gap differences are correct, but while the ITU’s indicator emphasises that the lower proportions of women than the proportions of men using the Internet, a women-centred reference emphasises how much more likely men are to have Internet access than women. The Web Foundation observes that the lack of standardising around either a men- or women- centred indicator means the figures are used interchangeably. This certainly contributes to losing focus on the gap that the indicator is intended to show, and makes it difficult to monitor progress in closing it. For instance, according to the ITU, Africa is the only region where the gender gap widened from 20.7% in 2013 to 25.3% in 2017. This means that in four years the proportion of women using the Internet, relative to men, has decreased by 4%. The Web Foundation’s Women's Rights Online Global Report was published in 2015, and the first Inclusive Internet report in 2017, and I was unable to find ITU’s disaggregated statistics of Internet penetration in 2013. Thus, I was unable to calculate how much less likely women now are to have access than men, using a women-centred reference, for comparison purposes.

The Web Foundation observes that the lack of standardising around either a men- or women- centred indicator means the figures are used interchangeably. This certainly contributes to losing focus on the gap that the indicator is intended to show, and makes it difficult to monitor progress in closing it.

The Inclusive Internet report notes that, according to one advocacy group, if current trends continue, 71% of female Africans will be offline in 2020, compared with 48% of men. Their extensive surveys make it clear that women’s lower adoption rates are not merely a shortage of access but the result of wide ranging social, economic, infrastructure and content-related factors. Therein lies both the main importance of a women-centred, rather than a men-centred, indicator - but also its problems.

The Web Foundation states that “we can more accurately understand how many more women need to come online in order to reach gender parity". Certainly posing questions around why men’s use is “the measuring stick for women’s internet use" can be a valuable rhetoric in drawing attention to the deeply gendered infrastructures of telecommunications industry and international policy-making. Such questions can provoke reflecting on what real access is for women, and what internet use might mean in women’s lives. However, unlike the Web Foundation, I do not consider a women-centred reference in calculating an indicator either represents a “women-centred perspective", nor conveys the wide variety of situations that women experience.

An indicator is not really a women-centred perspective, it is a perspective that somewhat abstractly sums up a multi-faceted situation.

An indicator is not really a women-centred perspective, it is a perspective that somewhat abstractly sums up a multi-faceted situation. The Web Foundation’s more detailed statistics about key contributors to keeping women offline, such as education, skills and content available as well as affordability, illustrate how their access and use is a function of society more generally, and that technology perpetuates existing disadvantage. Any strategy to effectively address women’s disadvantage in access and use must, therefore, address all the many international and local inequalities in which the internet is situated. Gender gap indicators are not a new thing in assessing development, and most gender gap indicators of the many social, economic and infrastructure factors that ultimately will shape access to the internet, use men-centred references. Consider The World Economic Forum, which has used men-centred ratios for over a decade to calculate, for instance, indices for economic participation and opportunity (female labour force participation over male value), and educational attainment (female literacy rate over male value).

Given difficulties in finding historical disaggregated gender data it seems we might shoot ourselves in the foot by calling for women-centred references.

Given difficulties in finding historical disaggregated gender data it seems we might shoot ourselves in the foot by calling for women-centred references.

- Firstly, we will be less able to assess relationships, say between internet use and wider economic participation, or between internet access and educational attainment.

- Secondly, as illustrated with some historical data, we might be limited in monitoring changes in indices over time in assessing the ways technology can amplify disadvantage.

Image source:Wikimedia Commons, Photo by published under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

A women-centred perspective on access to the internet is about the meaning of access situated in women’s lives.

A women-centred perspective on access to the internet is not merely a matter of calculating an indicator using a statistic about women’s overall internet penetration as a reference. Rather, it is about the meaning of access situated in women’s lives.

In the past six months I’ve had the privilege of working with women and men in the global south on the APC’s Local Access Project, where my role focuses on the social and gender impacts of Community Networks in rural areas. It is becoming clear, from research in two continents so far, that the meaning of access lies in the way many social, economic and infrastructure factors play out, or are resisted, in everyday acts of participating in the networks.

Digital gender gap indicators, like other indicators of structural inequalities between men and women, are certainly useful sensitization to the broader contexts of disparity and disadvantages faced by women in the countries I visited. Indeed, sometimes country level digital gender gap indicators were sound predictors of the rough proportions of women and men’s access to the community networks, and to the internet. However, this was not always the case, partly because all community networks studied were rural, where access is generally lower, and also because of more specific local, social and cultural approaches to gender. Active participation in organisational and technical decisions about the networks, which in turn shaped opportunities for access, sometimes resonated with indicators of educational attainment and income nationally; but not always.

Indeed, my early analysis suggests that what was more telling were details about the ways women negotiated access to the Internet and participation in the network. For instance, social expectations of women’s roles meant that women with technical skills had to manage their time more carefully to use the internet and participate in community network decisions, even in a country with a gender access gaps in favour of women. Meanwhile, even when women had access to something as mundane as instant messaging the nature of that access differed, and was situated in broader socio-cultural issues; for instance, women had significantly fewer and more restricted types of people in their WhatsApp contacts lists.

Social expectations of women’s roles meant that women with technical skills had to manage their time more carefully to use the internet and participate in community network decisions, even in a country with a gender access gaps in favour of women.

As, a Loc Access team-member - Steve Song, reminds that dangerous things happen when indicators become goals. Addressing the gap between women and men is as much about making visible and understanding many concerns that shape women’s access and women’s experience of access to the internet, as it is about meeting enumerated targets. To me, that seems to mean, as another Loc Access team member, Kathleen Diga sums up, the best use of our energies may be to choose an indicator of this gap and stick to it.

Addressing the gap between women and men is as much about making visible and understanding many concerns that shape women’s access and women’s experience of access to the internet, as it is about meeting enumerated targets.

An earlier version of this article contained edits that were unauthorised by the author. This version has been corrected.

- 5543 views

Add new comment