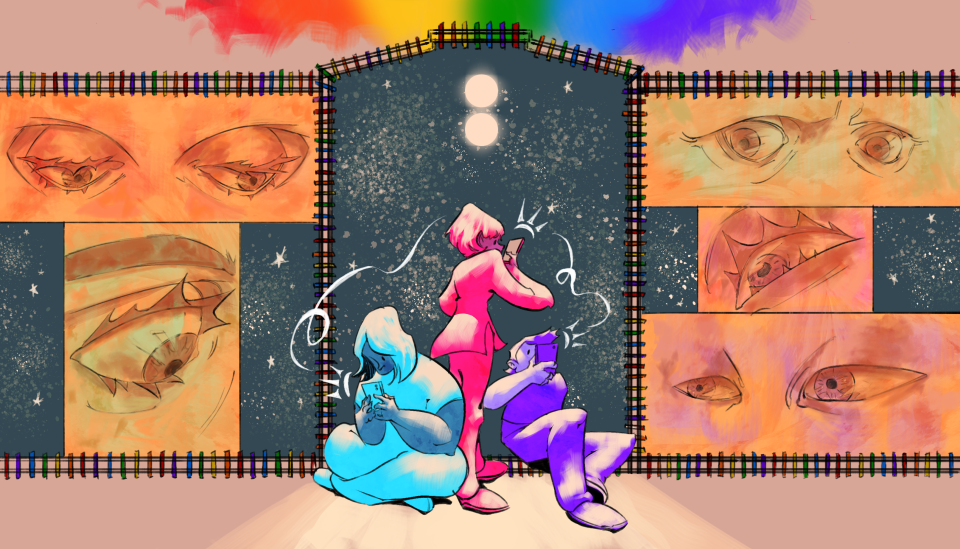

Queer individuals in Pakistan are constantly subjected to surveillance and live under threats of violence. Illustration by Fizzah

With the spread of social media, Pride, a movement that began in the West in 1970s, has become a digital experience, allowing for people in countries where it is dangerous to be queer, to take part in whatever capacity they feel is safe. With the prevalence of major digital platforms came trending Pride hashtags and generally globally available content around queer identity, especially in June when Pride month is celebrated around the world. While this opened up the event for so many who were historically kept away from it, it also opened the doors to hate – the kind which affects those who live in countries hostile to queer people. One such country is Pakistan.

Being Queer in Pakistan

Being queer, and engaging in same sex intimacy is illegal and criminalised in Pakistan under Section 377 of the Pakistan Penal Code. The section, ‘Unnatural Offenses’ reads, “Whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal, shall be punished with [imprisonment for life,] or with imprisonment of either description for a term which [shall not be less than two years nor more than] ten years, and shall also be liable to fine.”

This gives rise to already prevalent homophobia in Pakistani society where it roots from the ideology that homosexuality is against the order of God, and that queerness is a “Western” concept being enforced upon us. In a society that is as deeply Islamic as Pakistan’s, both religious and legal factors play out horribly for all queer people. The common belief here being that homosexuality corrupts society therefore outside the pale of religion.

As a queer person in Pakistan, my reaction to the existing homophobia is to morph my personality and my outward expression in as many ways as possible. I protect myself by masking my personality, by knowing where my safe spaces are and where I could be unsafe (digitally and on-ground). There are many people for whom breaking ties with their family and friends is an inevitable outcome of ‘coming out’ (or in a lot of cases, being outed).

The only group on the spectrum that is legally recognised and protected are the transgender and intersex communities, but even then, they are subjected to violence and discrimination without accountability. There is an ongoing genocide against transgender people in Pakistan, with murders being reported almost daily, the highest in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. In addition, in 2014, a paramedic in Lahore murdered three gay men he met online to supposedly “teach them a lesson”, he said. In 2015, a group of terrorists were captured for planning to kill gay people in Pakistan, because ‘they were spreading homosexuality at the behest of America.'

As a queer person in Pakistan, my reaction to the existing homophobia is to morph my personality and my outward expression in as many ways as possible. I protect myself by masking my personality, by knowing where my safe spaces are and where I could be unsafe.

Digitising Queer Experience

Due to prevalent social stigmas, queer people could not and cannot have any form of self-expression in physical spaces in Pakistan, which is why digital spaces became an important outlet. But the thing about digital spaces is that they are for everyone, and soon even they became unsafe.

I spoke with Sameen*, a queer woman who used to be Pakistan-based and ran an anonymous Twitter account back in 2012. She moved out of Pakistan in 2016 and is currently based out of the USA. “I made my account back then because Twitter in Pakistan was pretty small and I felt safe. I kept my account open because I wanted to reach out to more queer people and also thought my anonymity would shield me.” In her own words, she said that Twitter was a space for her to shout “my inner, most queer thoughts because I couldn’t very well go around Karachi and do that.” She notes a very significant change in the Twittersphere around 2017 and 2018, when her relatively small and “insignificant” account got attacked by trolls. These accounts blamed her for spreading immorality in the country, and also threatened her to reveal her true identity. “I received messages on Twitter from men claiming they had the ability to find my address and forcibly outing me in public, which was the scariest thought.” Sameen admits that in that moment, she fell for their messaging, “I went into a spiral, I convinced myself that they could track an IP address or something. I began to believe them and it consumed me.” She immediately deleted the account. Although she lived far away, she didn’t want to see what would happen if she didn’t comply. “Few of my followers did stand up for me. I do appreciate that kind of allyship, but how far can allyship really take us, given the monster that Pakistani Twitter has become?”

The hatred against queer people comes in waves, the proliferation of which seems to be a very well-oiled conservative machine that mobilizes followers behind a certain hashtag or a message, based on pre-existing homophobia that is reignited during these waves leading to a barrage of hate online.

How far can allyship really take us, given the monster that Pakistani Twitter has become?

In 2022, this hate was sparked when the US Embassy in Pakistan tweeted about teir work to empower the LGBTQ community in Pakistan, along with reaffirming their ‘mission’ to eradicate homophobia. Regardless of their good intention, the aftermath of the tweet directed unprecedented hate on the community.

Majority of the replies under the tweet called for the embassy to leave Pakistan, while others used the rhetoric of religion to reinforce homophobia as a counter-argument. In fact, the post got the country’s right-wing Islamist parties call the embassy out for disrespecting laws of the land, and put out a total rejection of the “values” they were trying to push forward.

Tariq*, a gay man based in Rawalpindi, says, “The tweet by the embassy was completely irresponsible, tone-deaf, and dangerous.” Tariq works with the transgender and intersex communities, teaching them digital skills. “The US Embassy acted poorly. They unleashed the gates of hate on us.” He adds, “They sit behind barbed wire, security guards, and guns. Who do we hide behind?” The anger in his voice is palpable, and completely justified. He relays how ‘irresponsible’ posts like these affect the people he trains, the trans community. “[The transgender persons] are already constantly attacked. Add in the additional layer of queer identity being a ‘foreign conspiracy’, and within seconds you’ve made the lives of people who are so obviously queer more and more dangerous."

Following that comment, Tariq laughs, “Sometimes we’re very quick to paint these communities as these powerless victims, and I literally just did that. The thing is, online, these women are queens!” He details how the community he works with is loud and proud online. I spoke to Saima*, a trans woman, a TikTok-er and an Instagram ‘star’ (by her own admission). “I am who I am. I fought to be happy, I still fight. We live in danger, but we thrive in it too! If someone hates me, that’s his problem, not mine,” she laughed loudly. She says, “I am happy and confident online. If someone abuses me on the internet, what’s the most they can do? Yes, we face real danger too. God forbid that dark day falls to me, or my sisters, but when it does come, I will leave it to God. I can go knowing I lived my life on my terms.” Saima’s purpose is clear: reclaim space and reclaim happiness for yourself.

But what the US Embassy did is not an isolated incident. Many global entities have disregarded local sensitivities thus making it possible to mould global communications to attack queer persons in Pakistan. For instance, during Pride 2021, TikTok had pushed very inclusive branding. Pride hashtags were shown as globally trending, and relevant content showed up on feeds in Pakistan too. Moreover, TikTok also reposted viral Pride videos on other platforms like Facebook and Instagram. While this content was being published by and reshared for the global audience that TikTok has, in Pakistan, it caused outrage amongst people. #UninstallTikTok became a top trend on Pakistan’s Twitter. TikTok has been a contentious app in Pakistan, with the app being blamed for spreading “immorality” and “indecency” in the country leading to four bans by the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority. The queer content during June 2021 being openly displayed was just part of a long list of grievances people had with the app in the country.

The tweets that users posted contained images that used religion and nationalism as a rallying cry against TikTok, and more broadly against homosexuality.

This graphic was shared in a tweet calling for people to uninstall TikTok in Pakistan for spreading homosexuality. The text in Urdu reads, ““Prove you are a responsible Pakistani by uninstalling TikTok: the app spreading homosexuality in the country.” Whereas, The man pictured in the background is Pakistan’s founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, and his quote at the bottom, “There is no power on earth that can undo Pakistan”, is used to evoke yet again the sentiment of nationalism. Source: Twitter

These calls are a rallying cry for some, but for others is the sound of impending doom. Haider*, a gay man based in Karachi, was accused for spreading the “gay agenda” when he posted a “Get Ready With Me” styling video, where during one shot he faces the camera and says, “Will I look too gay if I wear this”, referring to a flashy pair of shoes. He claims that his content was always made with the aim of depicting his true self, but he was careful not to use the word ‘gay’ ever. Haider admitted that he thought nothing of the two second bit of his overall video, but he soon was proven wrong. “A friend messaged me saying that my TikTok was being shared on Twitter under the #UninstallTikTok trend. She sent me the link and I quickly realised that one snippet where I used the word ‘gay’ was basically everywhere,” he said.

As a result, he swiftly deactivated his social media accounts in hopes that the hate would stop. “Laying low is what helped. The peak of the video being shared lasted very little mostly because I simply disappeared. If I had been online, fighting this, this would’ve lasted longer,” he remarks. He adds further, “It seems Pakistan doesn’t have a way forward for queer people. It’s scary. Just a few weeks back, someone in Karachi went berserk over Skittles Pride month packaging! That’s messed up!”

The experiences of others around me force me to rethink the expression of my identity. Something as simple as putting my pronouns (he/they) in my employers’ HR management tool is a challenge, not because I wasn’t sure that I identify as non-binary, rather because it was such a public declaration of my queer identity. Was I really ready to make such a statement while living in Pakistan? My mind immediately raced to the worst case scenario; an unaccepting colleague taking a screenshot of my profile, with my name and picture on full display. There could be no hiding from it. Changing my pronouns out of fear was needed but it also felt horribly wrong, almost as if the work I did to love myself and my identity was undone. But a week later, I changed it back to he/they, because I could not let fear control my life any longer.

Being queer in Pakistan is different than being queer in geographies where global trends are set, like in the North. There has to be a way forward, and Pakistani transgender rights activist, Dr. Mehrub Moiz Awan seems to have a response. In a recent podcast, Mehrub talks about how ‘Pride’, the celebration and what it stands for, is a Western concept that is rooted in the cultural context relevant there. There is a lot to learn from it, however, she claims that it is important to recognise and remember that while the Stonewall riots started ‘Pride’, the celebration and the propagation of Pride was taken over by caucasion, gay, and cis-gendered men. She says that for Pakistan to get to a point where people of all orientations can co-exist in peace, we have to decolonize our minds and go back to the rich queer culture of the Indian subcontinent. After all, regressive laws such as Section 377 of the Pakistani Penal Code are colonial legacies, wherein British colonizers enforced these laws and they remain codified not only in Pakistan but some other former British colonies as well.

The experiences of others around me force me to rethink the expression of my identity. Something as simple as putting my pronouns (he/they) in my employers’ HR management tool is a challenge, not because I wasn’t sure that I identify as non-binary, rather because it was such a public declaration of my queer identity. Was I really ready to make such a statement while living in Pakistan?

French sociologist and writer, Frédéric Martel, makes a similar argument in his book, “Global Gay: How Gay Culture is Changing the World”, a product of his travels to many countries to study gay culture, including Iran and Saudi Arabia. He says, “Gay people are increasingly globalized and often very Americanized, but they remain deeply rooted in their individual countries and cultures. In the era of globalization, openness to influence and rootedness in history are not mutually exclusive. Indeed, the local singularities of gay life and the heterogeneity of LGBTQ+ communities are strong, even when sheltered under the same flag."

I look towards the new generation, and the queer creators within them to revolutionise the way queerness is expressed and perceived on the internet. They are unafraid, even in a country like Pakistan.

We are here, we are queer, and we are never leaving.

- 2558 views

Add new comment