There’s a word – which is an entire multi-faceted concept in itself – which comes to my mind very often, whether I’m reading the news, working, talking with loved ones or following someone’s train of thoughts online.

Intersectionality.

The concept it expresses has always been at the core of my perspective of the world and of my work, exploring how technology can most effectively serve justice and rights.

So I decided to write about it, as it might turn out to be useful for others as well – next time you’re scraping data to investigate the patterns behind an issue, supporting a group in building their advocacy strategy, or making up your own mind before going to the polls.

Intersectionality: what is it

The term first appeared in legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw’s paper Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics (1989).

The theory of intersectionality focuses on how a wide spectrum of biological, social and cultural categories which characterise our identities (such as gender, race, class, ability, sexual orientation, religion, and more) interact on multiple and often simultaneous levels.

These intersections are what ranks us as citizens of higher or lower status (power) in the society we live in – possibly also ranking us so unfavourably that we find ourselves in a marginalised position. Marginalised individuals are often regarded as an underclass: society doesn’t provide them with equal access to basic material needs, work opportunities, education, welfare or health care.

Consequently, the interaction of the categories building our societal profile can contribute to social inequality and injustice, fueling forms of oppression towards groups belonging to one or more of these categories, which interconnect and ultimately create a whole system of discriminations intersecting with each other.

In her 1991 paper Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color, Crenshaw discusses the theory with a specific focus on the analysis of the race and gender dimensions of violence against women of color in the United States, and how their struggles had been ignored by both feminism and anti-racist movement. But she also highlights how the understanding of intersectionality can serve as a basis to address other kinds of marginalisations as well and how it can serve the aim to acquire social and political equality and improve democracy. In her words

” […] Intersectionality may provide the means for dealing with other marginalizations as well. For example, race can also be a coalition of straight and gay people of color, and thus serve as a basis for critique of […] institutions that reproduce heterosexism.

With identity thus reconceptualized, it may be easier to understand the need for and to summon the courage to challenge groups that are after all, in one sense, “home” to us, in the name of the parts of us that are not made at home. […]

Recognizing that identity politics takes place at the site where categories intersect thus seems more fruitful than challenging the possibility of talking about categories at all. Through an awareness of intersectionality, we can better acknowledge and ground the differences among us and negotiate the means by which these differences will find expression in contracting group politics.”

A tool for action

As human beings, we don’t have one-dimensional identities – we’re all a combination of biological, social and cultural categories. We’re living intersections, we’re multi-dimensional. And so are the issues affecting us.

So when we are designing a technology, a tool, a policy to sort out an issue emerging in any of the domains constructing our lives – politics, health care, security, labor, property, taxes, education, environment, media – adopting an intersectional perspective is greatly beneficial.

Intersectionality is a way to think holistically about how different forms of oppression (and privilege) interact in people’s lives, and as such is a concept with both a tremendous theoretical explanatory power and a substantial efficacy as an action strategy.

The decisions we take as member of a society (for example going to vote), as well as the methods we adopt to build tools aiming to solve issues affecting us and others in any type of context (especially contexts which are not part of our own individual experience, but that we’re working to serve), would tangibly benefit not only from an understanding of what intersectionality is, but also from applying its analysis into the issues we’re tackling.

Critiques about the theory have also been expressed, criticising it as a divisive approach which focuses on the differences between individuals instead of highlighting their commonalities to achieve a positive goal. But being aware of differences and act accordingly doesn’t mean being divise nor accentuating tensions. Aiming to deeply and objectively understand the complexity of our society, the intersectional perspective has grown from a realistic and tangible way to describe an issue to a precious tool to describe a solution.

Equipped with it, it’s now up to us making the most of the learnings achieved through an intersectional analysis of the issues we face, and create action plans (for soft- and hardware tools, platforms, strategies, advocacy campaigns, movements) which reflect that complexity.

There are plenty of projects and organisations adopting an intersectional thinking in their work. I’ll mention some, which don’t aim to represent a comprehensive catalog of case studies, but more practically a few interesting cases which can be helpful in illustrating some of the infinite number of ways this approach can be adopted to build a tool or action.

In its own words, “Mobile Voices (Vozmob) is a platform for immigrant and/or low-wage workers in Los Angeles to create stories about their lives and communities directly from cell phones”. The project (fully bilingual, in English and Spanish) started as a way to offer domestic workers based in LA a way to share the stories and get in touch. It’s now grown in variety and size of content, is edited by a group of immigrant workers meeting once a week to curate it – and it also has a sister tool, Vojo. Vojo can be used for projects all around the world, allowing to post stories from inexpensive mobile phones via voice calls, SMS, and MMS (no Internet connection nor smartphones needed).

Open Whisper Systems is “both a large community of open source contributors, as well as a small team of dedicated developers” building applications aiming to advance the state of the art for secure communication.

Among their apps: RedPhone, a free and open source Android app providing end-to-end encryption for your calls; and Signal, a free and open source iPhone app that employs end-to-end encryption, allowing users to send messages and make calls while keeping their communication safe. Both apps are available in more than 30 languages.

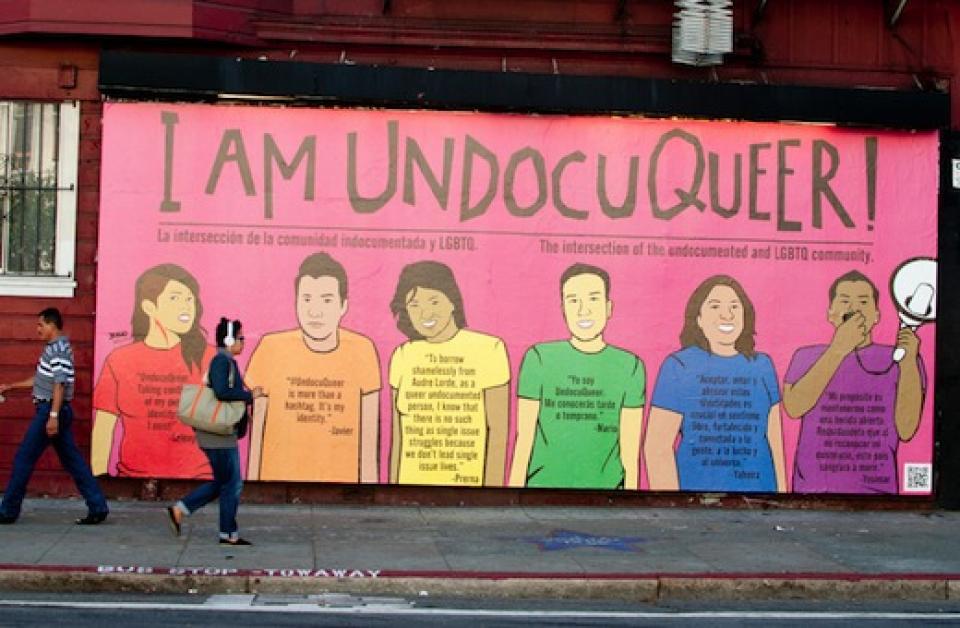

Undocumented queer immigrants are at the forefront of the fight for immigrant and LGBTQ rights in the United States. A multitude of intersections shapes their lives, as they experience exclusion from the country where they grew up, their communities, and from both the mainstream LGBTQ and immigration reform groups. The phrase often resonating in the movement – “ni de aquí, ni de allá” – sharply sums up their struggle: it reclaims the freedom to define what home means, whether in a geographic sense, within the community, or a gendered sense, within the body.

Actions and demonstrations led by activists such as Tania Unzueta (her speech Queer, Undocumented & Out greatly gives voice to the movement’s struggles), Lulú Martinez, Prerna Lal, projects like Julio Salgado’s I Am UndocuQueer poster series, make the most of the complex learnings coming from experiencing today’s society as both queer and undocumented immigrant individuals, and powerfully turn them into collective mobilisation, protests and actions, aiming to raise awareness, advance visibility and representation and challenge the biased policies ruling their lives.

How to make the most of it

So how can we translate the understanding of intersectionality into an action strategy both at an individual and structural level?

There are a multitude of steps we can take, and I’ll highlight the ones I find standing out the most for their efficacy.

At an individual level:

- Know the history which made the systems which are framing today’s contexts, the struggles and resistance movements which pushed its boundaries and the surviving mechanisms of the communities who are still fighting for justice and rights;

- Explore and understand our and others’ identity, the culture and society we live in, and the position we all have as part of them. Where do we benefit from the system and where we don’t. We are likely to find out that we qualify for overlapping layers of privilege and oppression – they constitute our own intersections.

- Focus on the systems of oppression and marginalisation experienced by us and by others, analyse them, their history and especially their power structures, so that we can build a deeper analysis of the challenges and crises we all face;

- Take responsibility for our layers of privilege in how we move about the world, especially as we learn to respectfully get in touch with, and work for, communities that we’re not a part of. Learn to be an ally.

At a structural level:

- Look out for the intersections present in the context we’re working on, remembering to apply a dynamic understanding of identity and intersectionality. Each context, community, issue we’ll work with will have its own intersections at play. We should never approach an issue bringing with us assumptions about the intersections we’ll find before having actually studied the reality of the context. We need to let the issues and the individuals affected by them tell us which are the dynamics at stake;

- But do not focus exclusively on the intersections, losing the the big picture on the entire system which includes them. Our goal is to analyse a problem in detail to come up with a more comprehensively shared vision for a solution;

- Do not perpetuate the inequalities we’re working to challenge in the first place, and therefore provide resources and access to those who don’t have them – in ways that are not tokenizing. And be very careful with the term empowerment – it implies that the “empowered community” of choice didn’t have its own power before our intervention: in some cases this is true, but in many this is actually an overstatement from our side;

- Hold ourselves accountable, especially when tense dynamics arise during the working process (as they’re likely to);

- Don’t make it symbolic nor transactional, make it transformative. Intersectionality isn’t something that you can carelessly apply to the surface of a campaign, nor an exchange of favours. It should fuel alliances to reframe what used to be a divisive issue into a shared value;

- Evaluate when it’s the case to go beyond short-term single-issue funding. This is a call to funders: consider when the goal you want to be achieved could benefit from a) the offer of grants aimed to support work with an intersectional approach (instead of a single-issue approach) and b) long-term funding (which, differently from short-term funding, can more effectively support a holistic modus operandi).

Why underestimating intersections is not an option

Technology and policies aiming to fuel and defend justice and rights should not only reflect the complexity of issues, but the complexity of people’s lives. Our lives and identities are nuanced and interconnected and so should be the tools and frameworks we build to make our societies work and improve.

Ignoring or minimising intersections and distinctions is not an option, as it doesn’t come without negative consequences. Underestimating them would end up allowing historical issues to keep doing their caustic work. Challenging them to adopt an intersectional approach will make our lives and the societies we live in more equal, safer and stronger.

This post was originally published in Beatrice Martini’s blog

- 7510 views

Add new comment