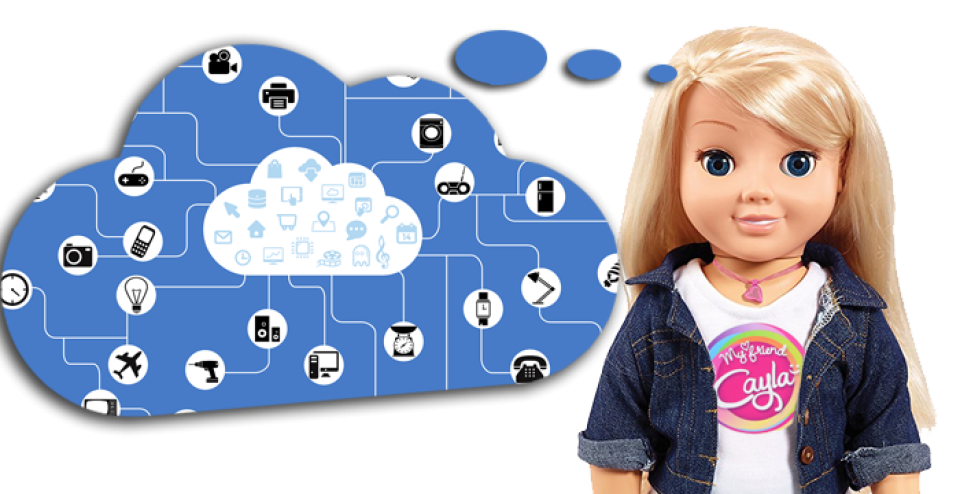

Image by Namita Aavriti, courtesy Cayla the hackable doll

If an object has a chip, it becomes smart, and by extension our houses become smarter – and so do our cities, hospitals, toys, phones. But what about the inventors, the creators, the owners, the users of all these smart and tiny things – are we becoming smarter?

I am fascinated by the ubiquitous ability of internet technologies to animate things, transform them into hubs, bypass walls and diminish distances. I am fascinated by the fact that behind all this infrastructure of the internet are simply cables of different sizes and length connecting computers, developing and integrating systems.

Now any object can become THE computer, the exchange point where data is transferred, collected and processed.

And in this continuum I feel exposed. It is not so much about the fact that the doll Cayla can see and observe the chaotic status of my bedroom or the uncleaned dishes. It is indeed disturbing that an object can potentially hack into my privacy and broadcast the inside of my home, or talk and reach out to little girls and boys. And what about the vibrator with integrated camera and light that can connect to the wi-fi and can shorten, almost eradicate, the distance with my lover. That too can be hacked and used for a bot-net attack against those others whose rights, beyond that of privacy, I care and defend the most.

The hacking in itself is more than disturbing – it is a permanent, potential status of aggression – but still to be hacked is also the state of being connected and using the internet

It is the RISK I have to confront every time. It is the threat that makes me think, learn and fight for a 360 degree right to privacy. And if I can isolate the intrusion – the third eye looking at the inside – I would say I feel I can manage. I can blind objects camera, I can disconnect them totally, I can think of using a VPN. So I feel I still have the agency as a user on how to use all these smart objects. I can engage in a strategy of self-protection and reclaiming of my privacy, and this is really essential and vital to sustain any interaction in a world mediated by technology and the internet. But there is more. There are two things that make me “hostile” and resistant to the current mainstream of the internet of things. These are the things that make me feel deprived of my agency, and they come even before the hack happens, even before the object is turned against me or breaches its own purpose.

First, is the continuous invisible collection of data that I have not consented to. The fact that both my metadata (log in, location pattern and so on) and my actual data (my own bits of images and sounds) are sent somewhere, to someone and I do not know to whom, for what purpose and for how long. And this is the default of any interaction data that has to transit from A to B and we, the users, do not know enough about what happens in-between.

First, is the continuous invisible collection of data that I have not consented to. The fact that both my metadata (log in, location pattern and so on) and my actual data (my own bits of images and sounds) are sent somewhere, to someone and I do not know to whom, for what purpose and for how long.

Second, is the shield of the innovation mantra – which allows for a de facto system that is irresponsible and does not hold anyone accountable for what could happen to me and my data. Because “innovation” cannot happen if rights are taken into consideration from the beginning. It seems that innovation is allowed the possibility to do damage, and only after that will the system start working on developing patches, either legally or technically.

The chip creator, the producer of the object, and all the intermediaries that see my data can easily escape any liability in the jungle of jurisdictions, proof and evidence, actual and perceived damages.

The chip creator, the producer of the object, and all the intermediaries that see my data can easily escape any liability in the jungle of jurisdictions, proof and evidence, actual and perceived damages. And again and again the users, the buyers, the citizens of this smarter and smarter connected world are left alone to manage their own desire, curiosity and need for the ubiquitous internet.

So again and again the users, the buyers, the citizens of this smarter and smarter connected world are left alone to manage their own desire, curiosity and need for the ubiquitous internet. They also have to deal with the threats and fear of the potential collection of any of their data, and the threats or risks of being hacked and abused.

The advices provided by many experts testers are: Do not buy the doll, do not fantasize using a vibrator. Or if you do then be aware, we have informed you! So, somehow the overall responsibility rests on the user.

The other advice, which scares me even more, is that we should rely on the innovation mantra coupled with the positive effect of competition. The defense of IoT is that it protects consumers, but only once the objects are on the market and people have been hacked and their rights abused. Big companies, such as FB, Google, Microsoft, … are more and more interested in artificial intelligence and the IoT is offering them the knowledge and the environment they need to better understand and innovate. And their business model reliant on users and customers will make sure they take care of our safety and privacy.

Well! They might be better at protecting our little secrets more than small producers of cheap objects, things, dolls and so on, but their business model is heavily reliant on DATA, the big data the millions of their user base provides them for free every instant of our connected lives.

They might be more careful about protecting our data (the images, the sounds) but their hunger for our metadata and behavioral pattern has no limit. And beyond this they are careful in their lengthy Terms of Service to not take responsibility, especially in the case of a breach or hack and subsequent exposure and abuse faced by the user. The user is once again alone in asking for justice, in controlling the damage and recovering from it.

In 2014, The Wire commented on the nature of the IoT.

As the Internet of Things (IoT) continues its run as one of the most popular technology buzzwords of the year, the discussion has turned from what it is, to how to drive value from it, to the tactical: how to make it work.

IoT will produce a treasure trove of big data – data that can help cities predict accidents and crimes, give doctors real-time insight into information from pacemakers or biochips, enable optimized productivity across industries through predictive maintenance on equipment and machinery, create truly smart homes with connected appliances and provide critical communication between self-driving cars. The possibilities that IoT brings to the table are endless.

And that’s really scary because treasure hunts are brutal, and have never respected anything or anyone. The ethics of the big company are yet to be proven, as is their culture of respecting diversity.

Even if the doll Cayla and the vibrator with camera are superfluous and something that due to their cost can only be afforded by western middle class, there are a thousand applications of the IoT that pose serious questions around how architectural and data decisions are framed, and then used. We will ALL be profiled by a small group of potent companies; our data will serve as a specific economic model and the safety net offered to us relies solely on corporate responsibility.

We will ALL be profiled by a small group of potent companies; our data will serve as a specific economic model and the safety net offered to us relies solely on corporate responsibility.

We live in a world where more and more states force people into the digital without providing them the basic elements for an informed and meaningful consent. In this same world, affordability of the internet is far from realised, and big companies, from private telcos to tech giants, remain de facto the gatekeepers that hold the keys to the wonderland.

Clearly this wonderland for billions of humans is still a dreamland, and for many others what is still needed is the bare necessity for survival or the opportunity for a better life. It is just a minority that enjoy access and has a voice. Still these voices are fragmented by languages, cultures, privileges and so at the end, setting rules remains in the hands of the usual suspects.

We are all, already, involuntary inhabitants of the internet of things. And it is not about avoiding buying objects that will violate our rights, and mistakenly relying on market competition to get our right to safety and privacy to be implemented. The real issue around the IoT is how to frame innovation since the very beginning as respectful and dependent on a human right framework so that small as well as big innovators cannot test whatever they want, while we chase behind them, trying to contain the damage.

____

The text was inspired by attending two workshops at #RightsCon 2017 in Brxelles

The Internet of Things and Ubiquitous Surveillance, an #allmenpannel except for Wafa Policy analyst at Access Now and of course for Carly the recently famous doll that can spy and be hacked while interacting on demand. And another session one day earlier was Let’s Talk About Sex Toy Security, more balanced in term of gender participation and with very interesting comments around cultural patterns of language inspired by widely used terms in tech environment such as penetration test, and also about how they frame design and threat modelling.

In the two session the stars were Cayla the doll and a vibrator.

- 6976 views

Add new comment