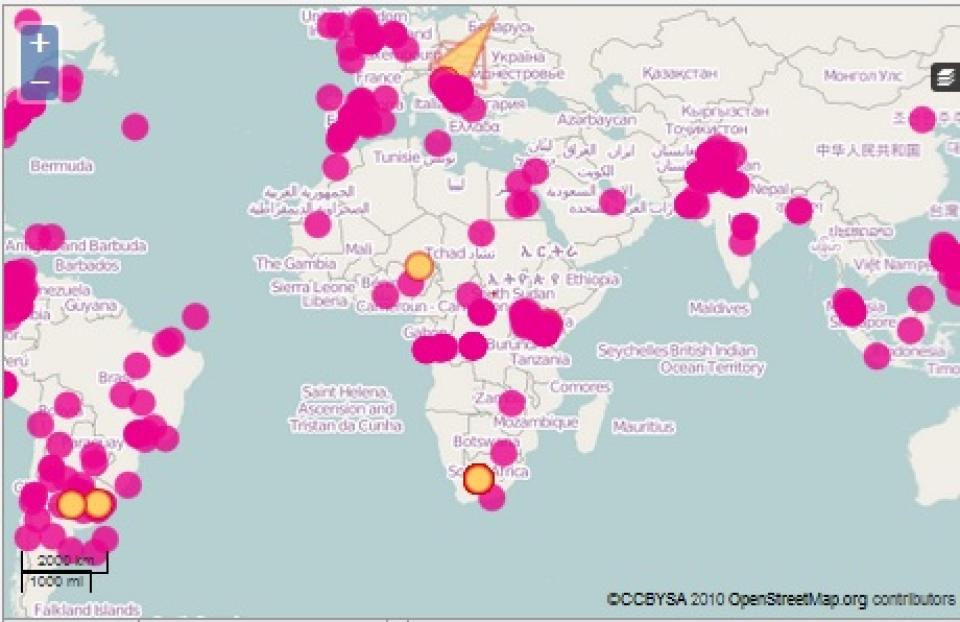

Over 500 hundred stories of women's survival and endurance and around 2000 incidents of violence against women (VAW) using online spaces and information and communication technologies (ICTs) are recorded in the Take Back the Tech! world map. Each dot bears silent witness to the hellish situations women have gone through for days, weeks and even months till they or someone who knew what was going on decided to speak up, to denounce, to try to stop the violence.

This new expression of gender violence came up in many subtle ways at first, but rapidly grew and changed to open online attacks, to blunt disclosure of intimate information via cell phones or social networks, making photos and videos go viral, and to the creation of websites to get revenge on former partners by uploading personal material that had been handed in trust, with no consent to be shared nor disseminated.

When the APC Women's Rights Programme (APC WRP) decided to use the Ushahidi map to collect information about the online violence that many women around the world were enduring, the aim was to gather evidence and show how ICTs can be used to perpetrate violence against women. APC WRP also wanted to use this information to raise awareness, get to the authorities and platform owners to provide answers and solutions to online VAW and commit to women's access to justice when they faced this violence. Working with survivors, anti-VAW activists and policy-makers to put an end to online VAW was also a top objective.

Analysing mapping results

In two years, from July 2012 to July 2014, almost 500 cases denouncing the use of ICTs and online spaces to perpetrate violence against women have been uploaded onto the map. Most of them came from the countries where the APC WRP and its partners organisations were working in the project “End violence: Women's rights and safety online”. Partners from seven countries took part in the project: Pakistan, Philippines, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Mexico, Colombia, Kenya, and Democratic Republic of Congo. APC WRP staff also contributed to map cases, including those shared by women in workshops, seminars and events where VAW and ICT issues were discussed.

Most of the cases mapped had been published in local or national newspapers, including websites, and other cases were denounced in blogs, institutional websites, reports by anti-VAW activists, and women's NGO's online bulletins. Many volunteers have contributed to mapping these cases, dedicating their time and expertise to help survivors tell their stories.

Mapping survivors

Though cases come from very different countries, they share many things in common. In spite of all the cultural differences, map data suggest a typical profile of a woman who experiences harm online:

- She is likely to be between the ages of 18 and 30

- The violation is likely to be perpetrated by someone known by her.

- It is most likely to happen on Facebook.

- It is mostly likely to be a form of emotional harm.

- This emotional abuse is likely to be repeated

- It is likely to involve threats of violence, emotional blackmail, or sharing private data (such as photographs) with others.

- She may take action to avoid or stop the violation.

- She is more likely to go to the police to report the violation rather than report it to Facebook.

- The police may investigate the case, but are not likely to investigate it.

As the table below shows, the majority of the cases reported are perpetrated by someone known to the person who experiences the violation (nearly 40%), followed by someone unknown (27%) and then by a group of people (15%). Violations by the State and an internet platform providers are reported to be the lowest.

The majority of the cases reported fall in the 18-30 age group, followed by the “under 18” age group, as can be seen from the table below. Together these make up to 74% of the number of cases reported where the violator was identified. Harm is also reported reasonably frequently for 31-45 years old (accounting for 21% of the total cases reported), but less so from the age group 46 onwards, only 5%.

There are possible explanations for this data, as younger women are the ones that use their cell phones, social networks and online spaces to interact and relate with friends and met new acquaintances more frequently. They also use online tools a lot, so they are more likely to write and report about their situation if things go wrong. The age group 45 and older are less likely to use the online mapping tool to report harm, though in general they are becoming good users of ICT tools and the internet. Then, we see that there's no mention to online VAW perpetrated against older women. It is also possible that the age group 60 and older are not internet active and are not ready to use online tools to report VAW.

Mapping the kind of harm survivors face online

What kind of harm do women face online? Are they easy to confront? Are women aware that online behaviours can be as dangerous as those happening offline? Recent studies in Spain show that most teenagers don't consider online harassment as VAW, for example.

The map shows us that harm does happen as a result of online VAW, and not only emotional harm, but also physical harm that might follow online harassment and stalking.

As the table above shows, the majority of cases (33%) are reported as “emotional harm”, followed by “harm to reputation” and “invasion of privacy” (both at 18%), with invasion of privacy being slightly higher. At nearly 11%, “physical harm” is strikingly high, suggesting that the internet is being used as an intermediate communication platform for direct physical violations, as opposed to the violation remaining online.

Most survivors who are ready to tell their story, say that at first they were petrified by the situation. They didn't know what to do nor how to find rapid solutions to stop online VAW and its consequences. After a first shock, most of them informed themselves and started to fight back. Some did it by themselves, too frightened or ashamed to tell friends or family. Others looked for help from people they trusted or denounced the situation to the authorities. Very few decided to report to technology platform providers, though most of the cases (26%) happened in Facebook or via mobile phones (19%).

These results also demonstrate that abusers prefer platforms which offer immediate, direct access, such as mobile phone and Facebook.

Who is ready to report?

In spite of the stressful situation survivors go through, many of them are ready to report online VAW. 56% of those experiencing harm are likely to take action, suggesting a sense of empowerment overall amongst those experiencing online harm. Then, 44% are not likely to take action, also suggesting the need for awareness raising and empowerment on the alternatives for effective action when harm online occurs.

This table shows the main actions women take to report online gender violence:

We see women prefer reporting to the authorities (69%) rather than to the service provider (just 8%), supporting the observation that service providers are not seen to be sufficiently responsible for their platforms in terms of one person violating the rights of another. This is relevant, for as we have seen before, most of the violent situations women had to bear happened in Facebook or via mobile phones.

Then, while a number of cases are reported to authorities (49% of actions taken), less than half of them appear to have been investigated by the authorities (nearly 41% only). This suggests a legal disconnect between online harm and those empowered to take action against other forms of VAW, such as the police or the legal framework.

This is possibly due to online harm not being taken seriously enough by authorities, or the lack of a sufficient policy environment that protects the rights of those harmed online. The person reporting the case is also more likely to enter into a dialogue with the aggressor than report the incident to the service provider, suggesting the potential of further exposure to harm.

Next steps

This analysis and mapping of violence against women using information and communication technologies, social networks and internet spaces is part of a bigger project. It includes research in the seven countries mentioned at the beginning of this article, with case studies and analysis of anti-VAW and cybercrime legislation in each of those countries. Further research about the role of internet platform providers in taking actions to stop VAW will complete this endeavour.

All this information will help to produce clear recommendations to policy-makers in governments, international bodies and ICT private companies, encouraging them to have a new look at anti-VAW policies in a society where growing numbers of the population have access and use ICTs regularly to communicate and relate to each other. We need to be aware that online spaces are a place where power is disputed, and gender relations are included in this dispute.

- 17725 views

Add new comment