If there’s anything I love with a passion, it’s kicking serious ass. Which is probably why, as an 8 year old, Dangerous Dave inspired equal amounts of angst and satisfaction in me. In this simple 8-bit video game, I overcame obstacles and struggled through levels, overusing my jet-pack privileges and never quite pressing the Alt-key fast enough. Okay, maybe I wasn’t a particularly good player, but I eventually made it to the end, feeling invincible for exactly 30 minutes.

When I was growing up, I had the privilege of accessing almost every PC game that came folded into my dad’s monthly Digit magazine subscription. I toted powerful plasma guns in the shooter game Quake, sent my two-headed hydra in for reinforcement while battling rival villages in the strategy game Age of Mythology, lived out my happiest magical fantasies in the Harry Potter game series, hacked into other users’ accounts on Barbie.com (it’s not too hard if everybody’s favourite colour is blue), and helped the My Scene girls get dressed for parties or um, go to the mall.

Dress-up games were embarrassingly addictive, but oddly enough, these online girl worlds became a way for me to forge a vague identity for myself. Character choices were similar across games: the girly girl, the artsy loner, the animal loving hippie, the rocker chick, and the odd-but-cute geek. Despite being ridiculously fun, I was thankful for the other game options I had, because at some point I definitely got tired of shopping addictions and inane problems. Oh, Chelsea’s going to buy that cute top you had your eyes on, huh Nicole? Well that’s too bad, maybe you should go home and think about what your life has become.

To an outsider, the world of gaming may conjure up images of trigger-happy slacker boys who are socially inept escapists, emanating a distinctive smell of wet socks. But this couldn’t be further from the truth.

What’s broadly referred to as ‘gaming’ is actually a vast and varied terrain spanning casual games, of which PacMan is considered the first, everyday mobile games such as Candy Crush, arcade games including simulated bike and car racing, and ‘serious’ games that boast complex narratives and gameplay, and require substantial investments of time. Deviating greatly from the geek-boy stereotypes it exudes, the gaming industry is of massive commercial and cultural significance.

Oh, and it happens to include more than just a handful of girls.

In 2010 The Economic Times carried an article reporting that women accounted for nearly 20% of the total gaming market in India, estimated at around 5.8 billion that year — a percentage that was expected to double over the following three years. Now 20% may seem small, but what these numbers don’t account for is both the subsequent boom in the gaming industry over the past 5 years, as well as the various barriers women gamers have had to surmount.

The advent of serious gaming in India in the early 2000s led to a dramatic gender gap in gaming demographics, where marketing efforts were, and continue to be, directed towards boys and young men. In turn, young girls who might be interested in videogames have fewer relatable options or role models. What’s more, gamers in India don’t have it too easy. Tech is expensive, tournaments are sporadic and disorganised, and gaming isn’t high up in the sanskaari good books. Parents can’t seem to decide how they feel about gaming and they can’t be blamed, given that newspaper articles flip-flop between insisting videogames can ‘cure’ autism or else turn your child into an asocial troll.

Despite these numerous disincentives, gaming is quickly gaining popularity across the country. And while the scene isn’t exactly teeming with female gamers and subreddits dedicated to them, there is undoubtedly a small and resilient number that have started to make their presence felt. And for the most part, Barbie.com rarely features in their lives.

********

23-year-old Reisa Nongrum began to play video games a little over a decade ago at a small gaming café in South Mumbai. Wired was an airy, well-kept space with a painted glow-in-the-dark dragon peering over the thirty odd players stationed at their computers. Despite a strict no-food rule, the cafe’s denizens would play for 16 hours at a stretch on some days. Starting off with generic car and bike racing games and later moving on to the popular shooter game Call of Duty, Reisa played with a group of boys who, over time, became her proxy family.

It was at Wired where Reisa was introduced to the popular Multiplayer Online Battle Arena (MOBA) game, Defence of the Ancients (DotA). MOBAs are one type of massively multiplayer online game (MMOG), capable of supporting large numbers of players simultaneously. In DotA, multiple players form two clans, or teams, that fight each other to ultimately destroy the rival team’s ‘ancient’ building. Calling the game immersive would be a giant understatement.

‘I played it nearly all day, every day, for three years,’ Reisa recalls. ‘When DotA became available on Steam [a digital gaming distribution market allowing users to play online], I no longer had to leave the house to play.’ Constraints on time got harder as Reisa dropped out of college to start her own restaurant, which took up 18 hours of her day. ‘I’d do just the bare minimum when it came to anything non-DotA related. I had to eventually stop playing the game just so I could get on with my life.’ Reisa imposed a self-ban to see if she could restrain herself from DotA for a year. Her experiment has been a success, but come 19 August 2015, she has every intention of jumping right back in.

The entrance of videogames into India coincided with the liberalisation policies of the early nineties, which opened up venues for import that rendered your auntie from America essentially useless during family visits. Nintendo Entertainment Systems were a rage across the country, with thousands of families thumping on their consoles and blowing on cartridges in unison — traditions that were strangely effective in optimising gameplay. Around the same time, arcade gaming began to grow into a booming sector. With a wide range of games, from air hockey to racing to dance games, arcades proved to be an important social space in which young boys and girls actively played together.

‘My dad had an MS DOS computer at his workplace that came with Prince of Persia. That was pretty much my first game. I must’ve been 7 or 8 years old then.’ Mea, a 27-year-old game designer and community manager working at EA Studios in Hyderabad, has a pretty familiar sounding gaming trajectory. Most veteran gamers started out with all the 8-bit glory of Prince of Persia (1989) and Mario Bros (1983), in which the now-recognisable 8-bit block graphics represented the computer architecture of the time. Both games are played with pixel characters who jump on mushroom men and tortoises to collect stars and jetpacks, or stab other shirtless men to avoid fatal drops on jagged rocks — all in order to save two hapless, pixelated princesses. As 90s kids we hadn’t yet experienced the full magnificence of the interwebs via our dinky dial-up connections, but biking through Napa Valley with a bunch of sociopathic characters from Road Rash really rounded up our semi-charmed kind of lives.

Some women’s forays into the gaming world came at a later stage. Rashi Chandra, a self-taught artist based in Noida, began her ‘romance’ with games after she joined gaming company Apra Infotech. Her mostly male colleagues were excited by the novelty of a female gamer, and introduced her to various gaming genres, encouraging her to play. There would, however, always be the one odd perplexing conversation about gender. ‘A few people seemed amused at my gaming. They often asked me whether I played Candy Crush or FarmVille, making jokes about those games being “girly”.’ Interestingly, while women do dominate the mobile gaming market and are often derided for their ‘frivolous’ interests, animator Daniel Floyd points out in his brilliant YouTube video ‘Video Games and the Female Audience’ that mobile gaming can serve as a gateway to more serious gaming for young women.

Rashi, currently a Witcher 3: Wild Hunt addict — the alleged new Mt. Everest of gaming with a vast open world structure — explains that her parents were always supportive of her, and sometimes even helped her buy hardware or software. For most gamers, though, parental concern often clouds their experience. While no parent needs a(nother) think piece to know that several hours of gaming may have unhealthy consequences, 21-year-old gamer Meghna Pradhan points out that their concerns are often misguided. ‘Earlier it was concern about us not acting like girls — me and my sister that is — along with fear that we will not do well on exams. Now, wrecking our careers is the major concern.’ To avoid her mother’s ire, Meghna resorts to online games and getting her cousins to smuggle in the odd offline game for her.

With time, videogames have developed more complex storylines, environments, and perhaps most significantly, characters that are carefully crafted personalities. As Runestone Studios game artist Alika Gupta says, ‘The characters are very well developed in terms of personality and motives. It’s not just a simple person running across the screen killing things.’ Most videogames have one of three character options: a pre-decided protagonist, a series of characters to choose from, or the option to customise and build your own character. In this way, videogames can become a way to experiment with various identities in controlled environments.

Perhaps the biggest player in the market of alternate virtual selves is Second Life (SL), a hugely popular online world that saw a monthly average of 1 million unique users in 2013. In SL, users create ‘avatars’ that go about their daily lives and interact with each other through an online chat system. When writer Nadika N, a Chennai-based intersex transwoman, logged onto SL for the first time in 2008, she hadn’t yet begun her gender transition. She tells me, ‘I joined Second Life for two reasons: one, to explore my gender identity and two, to learn more about archaeology.’ SL has had several educational gaming partnerships, and at the time, the University of California was using the platform to recreate a historical site. Nadika, who later went on to formally study archaeology, was drawn into the possibilities of avatar choices that SL presented. As you develop an SL avatar, you can choose to be, among other options, male, female, trans, an animal, a robot, an alien, or any combination of the above.

Looking back Nadika says, ‘SL helped not just in exploring my identity online; it helped me define it for myself offline, and build a network that supported me through various stages of finding that identity.’ During her time on the platform, her avatars were all either women or genderqueer, but greatly varied in their physical appearance — fat, thin, exaggeratedly hot, subtly pretty, some that looked closer to her real appearance, and some customised to look the way she wanted to after her transition. She goes on to say, ‘Being on Second Life made me think, feel, talk and react like a woman or a genderqueer person,’ and ultimately, there was not much disconnect between her avatars and her ‘real’ selves.

*********

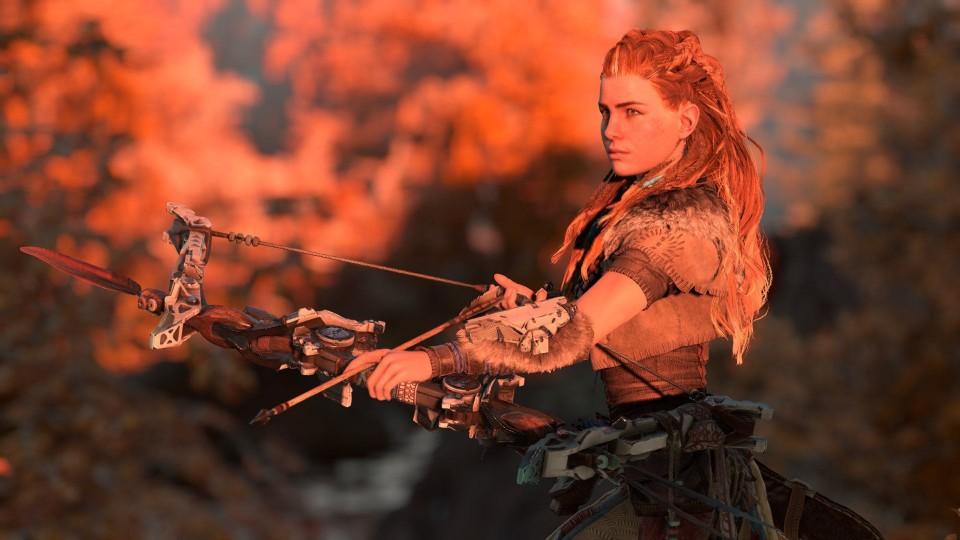

Last month, Los Angeles hosted the annual E3 (Electronic Entertainment Expo), one of the largest videogame trade fairs, used by publishers to introduce and advertise upcoming games. This year, E3 had big news for the gaming world: a slew of new female protagonists. The gaming industry has been severely criticised for not having enough strong female characters and for failing to reflect a growing demographic of women gamers. Where women characters do exist, critics often point out that they tend to be overtly and unnecessarily sexualised.

‘Dragon Age is more realistic with its women,’ Meghna tells me of the multi-award winning combat game in which players set out to defeat evil forces threatening their world. ‘If you expect Harlequin [a villain from the Batman games] to look like your modern American woman and not someone who should be getting backaches from the size of her chest, it’s not going to happen easily. But when Dragon Age: Inquisition did a more realistic character make [of its women], they got called ugly.’

Meghna compares Dragon Age to the Korean game Echo of Soul, a massive multiplayer online role play game, in which players collect the souls of the monsters they kill and use them to customise their avatars. She describes how her avatar, whose nipples are barely covered, is apparently only at a ‘medium skimpy’ level. ‘A guy came up to my avatar and commented on how great her tits were. But the silver lining was when he realised I was actually a girl playing and not another dude, and started apologising vehemently,’ she laughs. While some people argue that character attractiveness is a fairly reasonable demand from a fantasy game, the extra-sexiness of women characters can also sometimes make them less playable. For instance, armour for female characters in combat games has been criticised for being little more than bikini chainmail, making them easily susceptible to injury.

That’s just one way of looking at it though.

‘Sexy badass females are awesome,’ Niha Patil states simply. The 22 year old from Mumbai is a professional costumer, makeup artist, and cosplayer — a performance artist who uses detailed costumes and jewellery to dress up as different characters from manga, anime, comics and videogames. In this way, Niha has figured out a way to monetise both her avid interest in gaming and her costume design skills. Her Facebook fan page, Niha Novacaine, has over 7300 fans who log in to catch Niha’s frequent transformations into video game characters.

But to put yourself up for scrutiny on the internet is a difficult task. ‘I have to heavily moderate my page; the amount of hate mail I receive is ridiculous. The thing is, most people objectify cosplayers,’ Niha says dismissively. In fact, swimming through a sea of hate seems to almost come with the territory of being a woman gamer — or simply a woman — online.

In August 2014 the GamerGate controversy rocked the foundations of the gaming world. What started off as several positive media reviews of American developer Zoe Quinn’s Depression Quest — an interactive game in which players experience the world through the lens of someone who lives with depression — quickly escalated into a lot of very angry (and largely white male) gamers accusing gaming journalism of privileging social justice over the ‘quality’ of a game. Add to the mix Quinn’s ex-boyfriend, who devoted a blog post to detailing her alleged sexual partners, including one games journalist (who, incidentally, never reviewed any of Quinn’s games). Ignoring facts and claiming outrage over the lack of ‘ethics in games journalism’, GamerGate supporters went in for the kill. Quinn and her family received vicious online attacks: their contact details and addresses were made public, her accounts were hacked, and she received innumerable rape and death threats, all nauseatingly graphic.

In a continuing witch-hunt, GamerGate led to renewed harassment of game critic Anita Sarkeesian, whose web series Tropes vs. Women in Video Games examines the representation of female characters in gaming. Sarkeesian was forced to flee her home, and GamerGate supporters went on to lead similar attacks against other prominent individuals who expressed any support for these women. In this way, whatever interesting point GamerGate could possibly have raised about gaming journalism was drowned out in a barrage of misogyny and vitriol, all directed at a woman whose only ‘fault’, in their own words, was that she was an ‘ignorant bitch’.

Closer to home, perhaps what any woman gamer can relate to is the struggle to get a large number of male peers to take you seriously. Bhavika Tekwani, a Mumbai-based software engineer who has been playing videogames since she was in Grade 10 tells me, ‘They all accept you eventually, but I do this thing where I have to demonstrate how much I know or how often I play to be considered a “real gamer”. This has to be repeated every time there’s a new dude in the team. They automatically assume he is skilled, [but] they don’t assume the same for me.’

She adds on a darker note, ‘One of the worst things I’ve heard was when a guy told me that if I played a female character he could just “rape her and it’d be game over”.’ In her newly released documentary film GTFO (Get the F$@! Out), filmmaker Shannon Sun-Higginson takes on the daily, persistent misogyny that women gamers and developers are subject to. As one woman featured in the film explains of team games, ‘Every time I opened my mouth to say, “Hey dude, there’s someone coming up behind you” it was, “Shut up, bitch. Shut up, bitch”.’

Given the broader environment, it’s unsurprising that Bhavika concludes by saying, ‘I’ve never heard anyone call themselves a “girl gamer”. I think girls know that they’re supposed to draw as little attention as possible to their female identity to fit into male dominated circles.’ In fact, women gaming in India prefer to steer clear of mentioning their gender at all — unless they’re with a familiar group of people. Mrinmayi Sawant, founder of the digital media company TechByTheBay and ex-DotA fanatic explains, ‘Gaming is very male dominant in India. A lot of girls play without revealing their gender or pretend to be boys. I did too for a while. Only when I actually made some genuine friends did I disclose my gender.’

This sometimes works both ways though, with men preferring to play as female characters. Several men admitted that playing the female version of the protagonist in Mass Effect, a sci-fi game featuring an all-out intergalactic war, had been infinitely more interesting because of the brilliant job that voice actor Jennifer Hale had done. Another bunch of men ‘reasonably’ explained that if they had to stare at a bottom all day, they’d prefer it to be female.

As India’s small gaming scene continues to grow, and increasing numbers of girls and women join the thriving community, we can be hopeful that both men and women will stop treating women gamers as novelties — either to be deified or disregarded. Because ultimately it’s the experience of playing that pulls us in, and all you want from a videogame is to be entertained, challenged, and kick some ass along the way.

This piece was originally published in Medium by Deep Dives as part of the series Sexing the Interwebs

- 8604 views

Add new comment