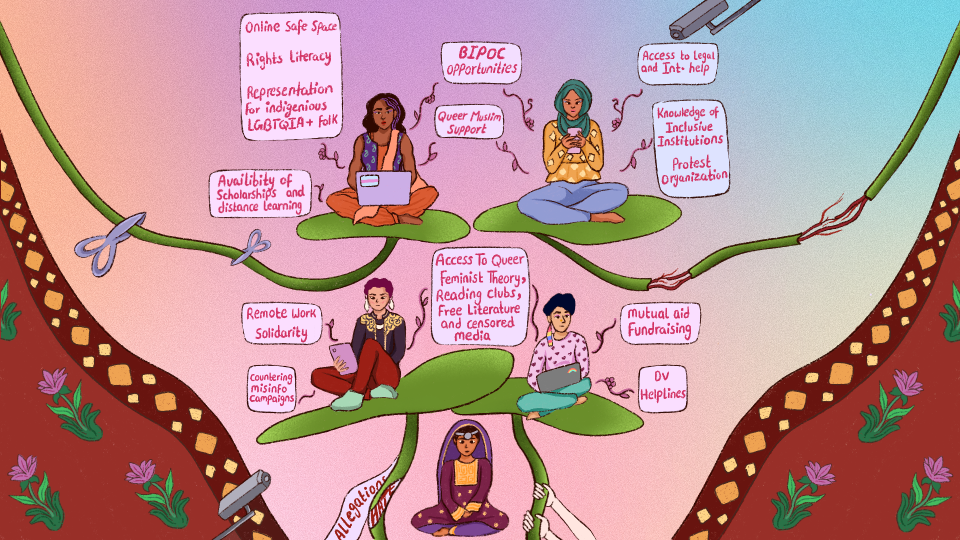

Barriers to digital access for women, non-binary and gender diverse folks restrict them from accessing full potential of the internet. Illustration by Mashaal Sajid for GenderIT.

Despite the boom in the usage of the internet and technology in the past few decades, gender digital divide continues to be a hindrance around the world that bars women, non-binary and gender diverse people from accesssing the full potential of this communication marvel. In the last three years since the COVID-19 hit the world and disrupted every aspect of life, the magnitude of this digital divide has become all the more prominent as women and marginalised folks struggled to continue many basic tasks that now depend on digital access.

According to GSMA’s Gender Gap report for the year 2022, women are 16 percent less likely to use mobile internet, and 7 percent less likely to own a smartphone. Their access to the digital technologies is heavily reliant on available disposable income that the family is willing to dispense on the internet which is still considered a luxury. Even though the necessity of technological access cannot be contested, for many around the world, and mostly in the Majority World or the Global South, internet access and enabling devices are still a want than a need that often takes a backseat as families prioritise meeting other basic needs of food, shelter, clothing and healthcare, leaving no room to afford the internet or a digital device. The situation is very relevant in South and Southeast Asia where even the cost of digital access is the lowest as compared to the rest of the world, yet it continues to be unaffordable or inaccessible for the majority of the people in the region.

The Global South makes up the majority of the population of the world, and is also home to most of the low income countries, some of which also make up the majority of the South and Southeast Asia. This region is amongst the most poverty stricken lands, and makes it difficult for the residents to afford basic and essential necessities. As a result, the internet becomes an afterthought, even when it is needed rather than a want that can be ignored. However, the impact of this poverty is not uniform among the residents, rather the nuances of this effects can be seen in how women and gender diverse folks experience it compared to cisgender men.

The International Telecommunication Union states in its May 2022 report that, “Across Asia and the Pacific, an estimated 54 per cent of women use the Internet compared to 59 percent of men, reflecting a comparable digital gender gap amid lower usage overall.” Owing to this gender gap, it is speculated that the digital inequality will translate into economic inequality barring women in ASEAN countries from accessing the many financial benefits of technology. It is known that the lack of and controlled digital access has direct implications on the way women’s lives can be improved in patriarchal societies.

Given the patriarchal and conservative control over gendered bodies, it often becomes impossible to challenge the status quo, and as a result, the already marginalised individuals are further ostracised and denied access to the larger world and the opportunities that the internet brings.

Geographical barriers, financial restrictions, infrastructural hurdles, lack of digital literacy, increasing gender based violence, and patriarchal control, all contribute towards the digital divide that impacts women and gender diverse folks more than it impacts other individuals. These communities find themselves struggling to negotiate their access in exchange for other needs and freedoms, if at all. Given the patriarchal and conservative control over gendered bodies, it often becomes impossible to challenge the status quo, and as a result, the already marginalised individuals are further ostracised and denied access to the larger world and the opportunities that the internet brings.

This edition that focuses on the stories and experiences from South and Southeast Asia, explores deeper into the issue of gender digital divide in six countries, including Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Myanmar, Indonesia and Malaysia, through multi-format stories written and drawn by local writers and artists who understand and have experienced the nuances of the discussion of technological gap in their respective countries. The stories delve into the larger theme of access to the internet, with sub-themes focusing on patriarchal control on access, affordability, online gender based violence and its impact on access, lack of digital literacy, and community resilience.

For example, where the internet opens avenues for employment and educational opportunities, women and young girls lose these chances as they are refused access by the men of the house on the pretext of other men gaining easy access to them if they are connected to the internet. In many households in Indonesia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Sri Lanka, for example, women and girls depend on the permission of men in their house to use a mobile phone, let alone own it. In Afghanistan, the new Taliban government has banned the telecom companies and shop owners from selling mobile SIM cards to women, resulting in a wider gap in their independent ownership of mobile phones and access to the internet. Women and young girls not only depend on men around them for their financial needs, but also for their technological usage. In Afghanistan, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, the impact of this digital divide was found to have direct impact on everyday lives of women and gender diverse folks, including on their basic communications, work, education, entertainment and self-expression, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdowns to control the spread of the virus. Women were barred from accessing it as they juggled between domestic responsibilities that were dumped on them, whereas, others were suffering because of the unaffordable device access. In Myanmar and Malaysia, online gender based violence and the need to constantly put yourself out there that leads to surveilling eyes consistently looking for more content to see and attack, has led to women and LGBTQI+ folks being vigilant of what they post and how they post it. They find themselves over-analysing their social media activities, and overthinking every post they make, often leading to self-censorship in hopes for the potential abusers to not find them on the internet. The stories explore how technology that enables and empowers women and LGBTQI+ folks in many ways, also becomes a weapon for their oppression at the hands of those who aim to confine them. The relationship of technology with identity and existence is seen from a lens of the oppressed, and despite the ability of digital devices becoming ground zero for gender based violence, writers and artists shed light on the resilience of the marginalised folks and how they fight back everyday as an act of taking the power back.

In rural villages in Indonesia, the internet continues to be unavailable and unaffordable for low income communities, so they found another way to connect with the world amidst information blackouts during COVID-19. The residents of two villages formed community radios that became a primary source for the locals to get critical information about healthcare, work opportunities, safety and education for everyone. These radios provided a way for everyone to be updated with information needed to stay safe during the pandemic while also ensuring their daily life is not crippled. This is not only about the community’s ability to come together and find solutions to their problems themselves, but also a reflection on the governments’ failure to provide essential services to communities structurally left-out from the discourse of rights-based policymaking.

Gender digital divide is a form of gender based violence designed to keep marginalised folks from accessing public spaces as equals.

The edition, which comprises six stories from different countries, looks at the impact that the gender digital divide has on the lives of already marginalised individuals; how it further enables offline and online violence against them based on their gender and sexuality, and how they have to brave up everytime they navigate or occupy online spaces. The offline violence that limits the potential of many of the women and gender diverse folks also translates on the internet if and when they manage to go online, forcing them to negotiate their expression which often leads to abuse.

Studies have found that gender digital divide is not just a mere inconvenience, rather it directly impacts the country’s economy as much as it promotes exclusionary treatment towards women and gender and sexual minorities. It is a form of gender based violence designed to keep marginalised folks from accessing spaces as equals, and coming forward as equal members of society with equal access to rights, opportunities and justice. It is a form of control to continue to keep them oppressed.

Internet access is a right, and denial of access is a violation of rights and the norms of justice.

- 699 views

Add new comment