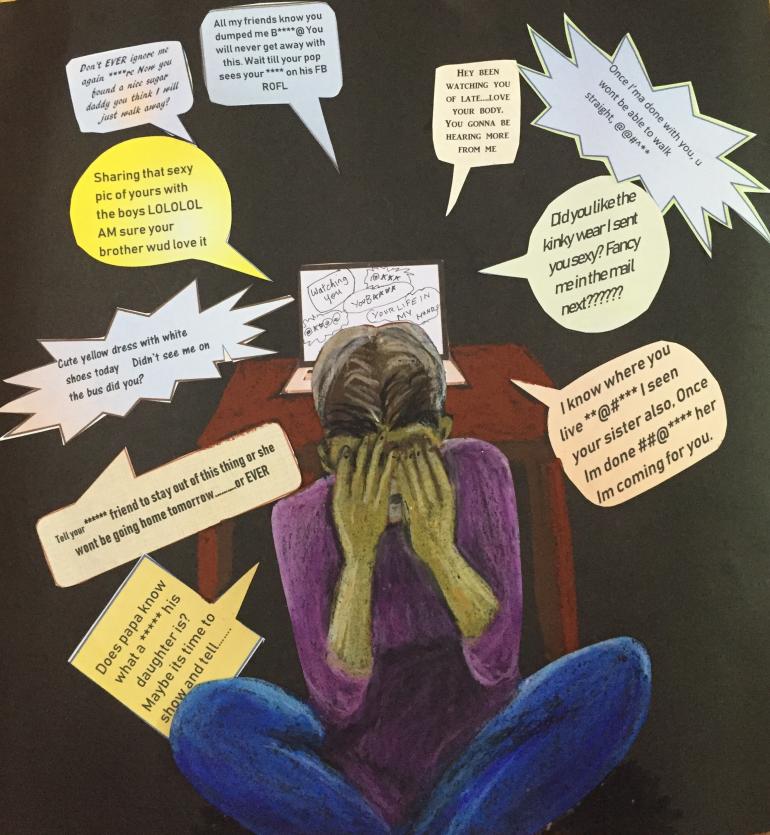

Still from video created by Digital Sister, as part of project by Centre for Gender and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights at the BRAC James P Grant School of Public Health, BRAC University (Bangladesh)

Growing up in Bangladesh, I experienced my first “wrong-number” phone call when I was 10-years-old, during the time of landlines, before we had mobiles or smartphones. Wrong-number calls would usually be initiated by young men who would dial a random number until they heard a young woman answer. Then they would try to strike up a conversation by asking the recipient a barrage of questions about their name, age, location, family, marital status and even daily activities. Over the years I heard stories of these wrong-number calls and how sometimes women on the other end would choose to have romantic relationships with them over the phone. But somehow these stories always ended up becoming cautionary tales of how these phone relationships would turn into something more turbulent.

Growing up in Bangladesh, I experienced my first “wrong-number” phone call when I was 10-years-old

The first time I answered one of these calls, the 10-year-old me knew something didn’t feel right. When the unknown caller asked me my name, I didn’t want to tell him. Generally, I had been taught not to engage with strangers. So I hung up and avoided answering the phone for the rest of the day. Thankfully he didn’t call back, but that doesn’t mean I never answered a wrong-number call again. Choosing not to engage with the caller became my method of dealing with them. More particularly, I was lucky none of these callers ever turned into an incessant stalker. But it was commonplace to hear stories of various degrees of harassment from wrong-number callers among my female friends. For those whose stories became a more serious problem, they rarely knew where to go for help.

Today with the rise of technology and fast-growing access to smartphones and the Internet, wrong-number calls have evolved into more sinister occurrences of online or “cyber” harassment where perpetrators can hide behind digital spaces, often making it harder to bring them to justice. A frightful statistic from a recent report by the Bangladesh Legal Aid Services and Trust (BLAST) revealed 73%of women internet users have experienced cybercrime. As of December 2017, the Bangladesh government’s ICT Division’s Cyber Help Desk reported receiving more than 17,000 complaints, of which 70% were from women[1].

According to a report by the POLICY project, Bangladesh’s adolescent population (ages 15–24) was estimated at about 28 million in 2000, and is projected to increase by 21% to reach 35 million by 2020. This is also the first generation of Bangladeshis to have access to affordable technological devices such as computers and smartphones with built-in Internet services. By the end of April 2018, the Bangladesh Regulatory Telecom Commission (BRTC) reported that the total number of internet subscribers was 85.918 million. More the 93% of these subscribers use internet on mobile phones, and the total number of people using mobile phones are more than 150 million.

As explained by Farhana Akter in a previous article, the scenario of Bangladesh is as so: While the expansion of ICT and growing Internet penetration across the country indicates nationwide development and that the Government is rapidly reaching its vision of a “digital Bangladesh,” there are some pre-existing social-physiological factors and inadequate legal protections that have resulted in more cyber violence against women.

There are some pre-existing social-physiological factors and inadequate legal protections that have resulted in more cyber violence against women.

Findings from our research

Young women are most vulnerable to cyber harassment, and this was evident in a recent research exploring the sexual reproductive health and rights (SRHR)-related needs of urban, middle-class young people in Bangladesh. Here female participants were very vocal about instances of harassment they faced online and their frustration about not knowing where to find a solution.

Under the study by BRAC James P Grant School of Public Health, BRAC University, we conducted focus group discussions (FGDs) with over 200 adolescents and young people between the ages of 15 and 24 in Dhaka and Chittagong–the two largest cities in Bangladesh. We were finding that whether it was among the male or female groups, at least one instance of cyber harassment was shared during every FGD. However, the female respondents were more likely to share negative stories that they experienced first-hand, rather than the male respondents who mainly reported stories they had heard about.

We were finding that whether it was among the male or female groups, at least one instance of cyber harassment was shared during every FGD.

When I listened to the young women sharing their stories, I couldn’t help but recall the stories my own friends and I had shared with each other about wrong-number callers from our own pre-teen and teenage years. Similarly, the young women discussing cyber harassment with me now were also left without any knowledge of whom to turn to for help.

With the proliferation of the internet and mobile phones in Bangladesh, use of social media platforms like Facebook has also increased; in 2017, BRTC reported that there were approximately 29 million registered Facebook users, of which 86% use it from their mobile devices. According to the most recent GSMA Mobile Gender Gap Report, at least one third of the subscribers of mobile phones and internet in the country are women. Stories from both our male and female participants revealed the most common platforms where they or someone they know faced harassment or cyberbullying were Facebook and Instagram. Sharing her experience, one FGD participant from a local private university told us she believed that experiencing bullying on Facebook was common among women her age. She said:

“I have been bullied on Facebook, in one of the university groups. My picture was posted there and someone wrote that I go to the cafeteria to get treated to free food by other people, and that I don’t pay my own bill. A lot of hurtful things were written there. I reported the cyberbully to Facebook, but the comments are still there.”

While Facebook and Instagram have created help centres to increase awareness about digital safety and site policies against bullying and harassment, perpetrators often find loopholes like making multiple accounts in order to keep pursuing their targets. A female FDG participant from an urban youth volunteer organization told us she had an online stalker who followed her on Instagram and persistently sent her inappropriate messages. In the end, she had blocked 57 accounts that the harasser had created to contact her; and she could keep reporting and blocking them, but it didn’t stop them from making a new account every time. This can be particularly unnerving for young people whose day-to-day lived experiences are now deeply influenced by their online behaviour and interactions[2]. While digital platforms have revolutionised the way young people communicate today, it also has many adverse effects such as an increased risk of mental health issues (depression, anxiety, etc.) due to cyberbullying and online harassment, particularly for young women.

In the end, she had blocked 57 accounts that the harasser had created to contact her

Texting and digital messaging are central way teens build and maintain relationships. But this level of connectivity may lead to potentially troubling and non-consensual exchanges. In a recent study by the Pew Research Centre about the online behaviour of US teenagers, a quarter of respondents said they have been sent sexually explicit images they didn’t ask for, while 7% said someone has shared explicit images of them without their consent[3]. One female participant of our study shared a story she had heard about another young woman receiving unwanted photos:

“Very recently, my friend got a message on Facebook Messenger with a picture of a guy’s genitals. I hear about these types of incidents very frequently. Guys send this kind of thing on social media. My friend was very courageous and she took a screenshot and sent it to all of his friends. And then that guy had to confess to sending it to her. So yeah, that is something that can also happen.”

Cyberbullies and online harassers alike can use photos of others without their consent in a variety of ways, including manipulation using editing software. A male respondent of our study at a local private university in Dhaka city mentioned hearing about people editing photos and using them to harass or extort young girls for money. He said, “They use Photoshop. You just paste another person’s head on to another’s body.” He said that this is done to create fake, “sexually-suggestive” photos and then shared among friends through various Facebook groups.

Another male respondent from a different private university shared a story where after breaking up with her boyfriend, a young woman was blackmailed by her ex who was still in possession of explicit photographs she had privately texted him while they were still together. Thus, with muddled lines between digital consent and relationships established online, young people in Bangladesh are not only vulnerable to cyberbullying and harassment but also perplexed as to how to overcome these issues.

Young people in Bangladesh are not only vulnerable to cyberbullying and harassment but also perplexed as to how to overcome these issues.

While the ICT Act of 2006 and the Telecommunication Act of 2001 is technically in place to help bring perpetrators of online harassment to justice, only a very small proportion of cases actually result in any form of legal action. Also, very little public information is available about legal resources in terms of cases of cyber harassment. A common concern expressed among our FGD participants was that perpetrators of online harassment can easily get away because they assume law enforcement agencies do not know how to handle these cases. More shockingly, some of the female respondents said they were afraid to report cyber harassment because they would be disgraced for getting into such a predicament in the first place. One of the female participants described her story of being “victim-shamed” when she approached the local police. She said:

“I was dealing with being harassed online and I wanted to find out the person’s identity, so I went to the police. But before I went, I covered my face with a hijab so that no one could recognize me. I had to pay a man to help me get the harasser’s SIM card registration number, but it was incorrect anyway. I didn’t pursue this further because it would end up costing a lot of money, and it would involve my parents' public image and mine. So, I just let it go.”

A common concern expressed among our FGD participants was that perpetrators of online harassment can easily get away because they assume law enforcement agencies do not know how to handle these cases.

There was a tone of hopelessness among several individuals who spoke about their experience with cyber harassment. No one was able to reach a solution, nor find closure; they all ended up enduring the torture, allowing it to take its course before eventually fading away–if they were lucky. Although the aim of this particular research was to identify the SRHR-related needs of urban, Bangladeshi youth, we felt that cyber harassment fit under the umbrella as one of the emerging problems that needed to be addressed for today’s young people. “I wish we knew more success stories of how girls overcame their harassers online,” said one young woman. Her words deeply resonated with us and as a result of these findings on cyber harassment, we decided to develop a short animation video to present the common scenarios and explain how to get help.

Making a video

Informed directly by the research participants, the animation video shows three common types of online harassment that were mentioned: cyberstalking, profile hacking, and fake social media accounts created using another person’s identity without consent. Based on the case stories, each scenario is presented as a problem that the character thinks they are facing alone. However, in the end, solutions such as the National ICT Helpline number are presented along with the message that no one should have to be alone in fighting against cyber harassment. Our goal was to encourage those feeling helpless in their own situations to at least find the courage to speak to someone they trust as the first small but significant step towards getting the help they need. We chose to include this message because we found most young people who spoke about cyber harassment and bullying said they were afraid to tell their parents or friends about what was happening to them in fear of being judged or shamed.

Our goal was to encourage those feeling helpless in their own situations to at least find the courage to speak to someone they trust as the first small but significant step towards getting the help they need.

Overall, the taboo around sex that exists in Bangladesh directly transfers into issues of sexual harassment because of cultural complexities around ideas of consent and society “frowning upon” any type of relationship between unmarried young men and women–whether it takes place online or offline. Although it is important to further investigate how to overcome such cultural barriers in providing SRHR-related information and services, the animation we produced serves to further emphasize how more research-informed strategies should be used to effectively deliver critical SRHR messaging to Bangladeshi youth using digital technology.

Research-informed strategies should be used to effectively deliver critical SRHR messaging to Bangladeshi youth using digital technology.

[1] Zaman. T., Gansheimer. L., Rolim S.B., & Mridha T. (December 2017). Legal action on Cyber Violence against Women. Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust and BRAC. https://www.blast.org.bd/content/publications/Cyber-violence.pdf

[2] Anderson M., Smith A., & Nolan H. (September 2018). A majority of teens have experienced some form of cyberbullying. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewinternet.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2018/09/PI_2018.09.27_teens-and-cyberbullying_FINAL.pdf

[3] Ibid.

References

- Akter, F. (2018, June 17). Cyber Violence Against Women: The Case of Bangladesh. Retrieved from https://www.genderit.org/articles/cyber-violence-against-women-case-bangladesh

- Anderson, M., Smith, A., and Nolan, H. (2018, September). A Majority of Teens Have Experienced Some Form of Cyberbullying. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2018/09/PI_2018.09.27_teens-and-cyberbullying_FINAL.pdf

- Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BRTC). (2018). Internet Subscribers in Bangladesh April, 2018. Retrieved from BRTC website: http://www.btrc.gov.bd/content/internet-subscribers-bangladesh-april-2018

- Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BRTC). (2018). Mobile Phone Subscribers in Bangladesh April, 2018. Retrieved from BRTC website: http://www.btrc.gov.bd/content/mobile-phone-subscribers-bangladesh-april-2018

- Barkat, A., & Majid, M. (2003). Adolescent Reproductive Health in Bangladesh: Status, Policies, Programs, and Issues. POLICY Project. Retrieved from http://www.policyproject.com/pubs/countryreports/arh_bangladesh.pdf

- Effects of Bullying. (2017, September 12). Retrieved from https://www.stopbullying.gov/at-risk/effects/index.html

- Halim, H. (2017, September 6). Only 2% Active Facebook Users in Bangladesh. Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved from https://www.dhakatribune.com/feature/tech/2017/09/06/2-active-facebook-users-bangladesh/

- Holson, L. (2018, May 1). Instagram Unveils A Bully Filter. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/01/technology/instagram-bully-filter.html

- Rowntree, O. (2018). Connected Women: The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2018. Retrieved from GSMA website: https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/GSMA_The_Mobile_Gender_Gap_Report_2018_32pp_WEBv7.pdf

- Zafar, A. (2016, June 27). Mapping Uncharted Territory – Sexual Rights and Reproductive Health of Bangladesh’s Urban Youth Using Digital Technology [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://jpgsphblog.wordpress.com/2016/06/27/mapping-uncharted-territory-sexual-rights-and-reproductive-health-of-bangladeshs-urban-youth-using-digital-technology/

- Zaman, S., Gansheimer, L., Rolim, S. B., & Mridha, T. (2017). Legal Action on Cyber Violence Against Women. Dhaka: Bangladesh Legal Aid Services Trust (BLAST). Retrieved from https://www.blast.org.bd/content/publications/Cyber-violence.pdf

- 36199 views

Add new comment