“That’s an excellent suggestion, Miss Triggs. Perhaps one of the men here would like to make it.” (Punch cartoon)

At the end of June I attended a workshop organised by the Centre for Studies on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information (CELE) at the University of Palermo in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on the topic “Digital violence and hate speech”, which dealt with the tensions between advocates for freedom of expression and the victims of online violence against women (VAW).

A trainer from Fundación Karisma in Colombia headed up the workshop, which brought together participants from Argentina, Mexico, Uruguay, Honduras, Chile, Brazil and other Latin American countries.

The trainer went through an explanation of the right to freedom of expression, its limits, and the role that anonymity plays in that field, especially when it comes to online VAW. She also shared the gobsmacking data that 74% of countries (out of 84 surveyed) are doing nothing to stop online violence, according to Web Index statistics.

“The internet offers possibilities but it also amplifies the inequalities,” the trainer stated. Young LGBT people experience three times more online harassment than other young users. Female journalists and women human rights defenders are also frequently among the targets of online violence and hate speech.

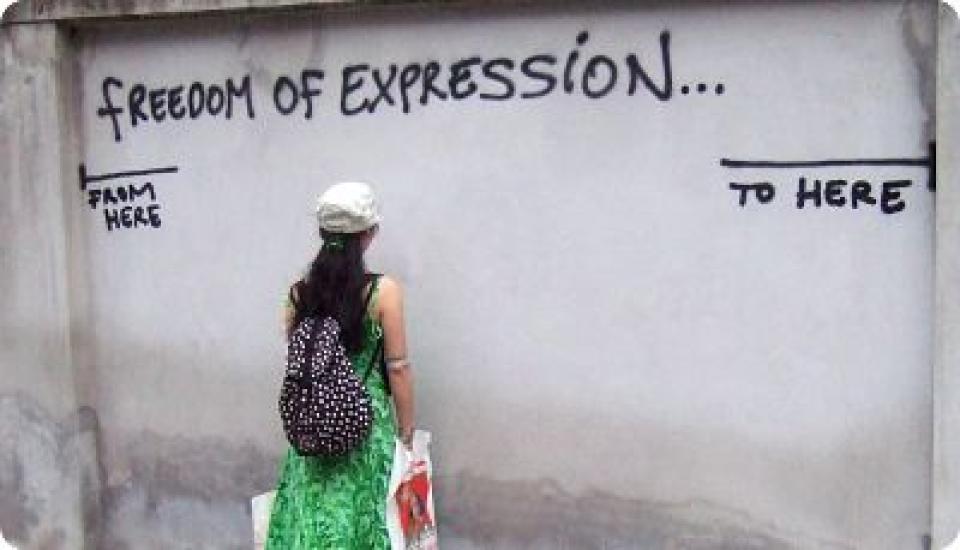

We have raised this issue before. In 2014, APC's Take Back the Tech! campaign focused on how online violence silences women's voices on the internet. Dealing with this topic emerged as a purposeful and timely decision of tapping and acting on this burning reality coming out in our recently launched research and constantly popping up among our partners and in the media. “Violence silences” was the motto of this campaign that advocated for women to be able to use their voices and express their opinions in the public sphere of the internet, and to empower them to exercise their right to freely express themselves without being afraid of threats and violent backlashes.

That said, and back to the workshop organised by CELE that I attended at the end of June, most of the cases shared there were about online attacks against women with high public profiles and not so much about ordinary women who happen to be going through this awful experience. Of course this makes sense, because high-profile women's statements have further reach and they are definitely more exposed to people's scrutiny.

Our research “From impunity to justice: Exploring corporate and legal remedies for technology-related violence against women” found three general categories of women who experience tech-based VAW: someone in an intimate relationship whose partner has become abusive; a professional with a public profile involved in public communication (e.g. writers, researchers, activists and artists); and a survivor of physical assault – often from intimate partner abuse or rape.

It is worth remembering that women in the public sphere are just one of the three profiles that our research identified as the most common among women experiencing online violence. Within this category, there are many cases of online violence targeting women journalists and women human rights defenders.

The other two categories identified, involving “someone in an intimate relationship whose partner has become abusive”, and “a survivor of physical assault” are the ones that are rarely portrayed by the media and the ones where the victims generally face a bigger struggle in accessing justice. Our research showed that access to justice for women suffering these attacks represents a huge struggle caused by the perception that violence that takes place online is not “real” and is therefore less harmful; the perception that technology-based VAW is a new form of violence and has nothing to do with other forms of violence; the perception that there are no legal remedies to deal with technology-based VAW; and the perception that women should just claim their rights if they want redress.

But here is the thing: all women are exposed to these kinds of violent online expressions perpetrated against them, just because of being women and speaking out about something in the public sphere of the internet. And one of the major outcomes of online violent attacks has been the silencing of these women, who are unable to find another resource to deal with this.

Women speaking up in the online agora

Famous cases of online harassment were mentioned during the workshop, such as the one suffered by female gamers like Anita Sarkeesian from Canada, Jenny Haniver from the United States, or Alanah Pearce from Australia.

Interestingly, Pearce decided to do something unusual when it comes to facing online hate speech: she sent Facebook messages to the mothers of four young boys who had threatened her online, based on the fact that many of the boys who threatened her were only 10 to 15 years old. When one of these women responded, Pearce shared the exchange with her 29,000 Twitter followers, using the well-known naming and shaming strategy.

The Fat, Ugly or Slutty website posts examples of harassment from all games – mostly screenshots of in-game messages that women receive from other gamers. Here is another example of women “daring to enter male territory” and the consequences of that. One of the hundreds of testimonies on the website reads:

“Me and my friends (another 3 girls) were playing a Gamebattles match against this guy and his friends. They were being very abusive via words like hoe slag etc in their clan tag. And this one guy kept sending me messages like this”

Grace, one of the site co-founders, says that although gamers can report harassment, there's a widespread perception that this achieves nothing. This perception matches the findings of our research, which revealed that “less than half of reported cases of technology-based violence against women (VAW) are investigated by the authorities.” In less than a third of the cases reported, action was taken by the service provider, and less than half of the cases reported to the authorities (41%) were investigated, although a relatively high number of cases (49%) were indeed reported to authorities.

Another of the online hate speech cases highlighted during the workshop – and one that generated lots of interest among the participants – was that of the British Cambridge professor Mary Beard, whose particular story became popular not only because she contacted one of her 20-year-old Twitter attackers, but because she also invited him for lunch and ended up writing a job recommendation for him, after realising that this young troll had no idea about that what he was doing could affect his job prospects.

Beard's reaction towards the perpetrator worked exceptionally well in her particular case but cannot be considered the general rule, and neither can Pearce's. As a matter of fact, I think it might work only on very few occasions and, above anything else, when the woman being harassed has had no direct contact or previous history with the harasser, which is not the case of the two other profiles of women identified in our research.

Besides this, I basically want to question this idea that came out during the debate that took place after mentioning Beard's case. It was said there that internet trolls act out mainly because of ignorance. Ignorance about what, you may ask: ignorance about what they are doing, or the extent of the harm they are causing, perhaps?

My take on this is the following: there is a component of ignorance in their actions; I will concede that to internet trolls. But I wouldn't say that this component relates to the naivety of not knowing that they are harming a woman by attacking her and stating something like “I will rip your head off, you cunt.” I would rather say that the ignorance, if any, lies in the fact that internet trolls are completely unaware of how unoriginal they are being in their actions and how much they are inserted in and functional to a patriarchal system that has always tried to silence women's voices.

As Mary Beard herself revealed, the silencing of women is reflected in Western literature since the times of the classical Greeks. And here is where the ignorance might lie: internet abusers are themselves the living examples of pure misogynistic history, now acting out on a modern technological platform. And women are being attacked for speaking out, as has happened since the beginning of times in our society.

Beard gave a very interesting lecture in 2014 on this topic under the title "Oh Do Shut Up Dear" about the public voice of women. The Cambridge professor took a long view on the “culturally awkward relationship between the voice of women and the public sphere of speech-making, debate and comment,” arguing that if we want to “understand – and do something about – the fact that women, even when they are not silenced, still have to pay a very high price for being heard, we have to recognise that it is a bit more complicated and that there’s a long back-story.” I think her analysis is right on spot and applicable to what we call nowadays “internet trolling”.

She begins by tracking what she says is the first recorded example of a man telling a woman to shut up and telling her that her voice was not to be heard in public, this taking place at the very beginning of the tradition of Western literature, more precisely at the start of The Odyssey, where young Telemachus says to his mother Penelope: “Mother, go back up into your quarters, and take up your own work, the loom and the distaff … speech will be the business of men, all men, and of me most of all; for mine is the power in this household.”

Right where written evidence for Western culture starts, women’s voices are not being heard in the public sphere. Another example of this goes back to the Roman world, with Ovid’s Metamorphoses (as Beard explains, that extraordinary mythological epic about people changing shape), which repeatedly returns to the idea of the silencing of women in the process of their transformation: Io is turned into a cow by Jupiter, so she cannot talk but only moo, while the chatty nymph Echo is punished so that her voice becomes merely an instrument for repeating the words of others.

Beard recognises only two main exceptions in the classical world to this “abomination of women’s public speaking”: first, women are allowed to speak out as victims and as martyrs – usually to preface their own death; secondly, women could legitimately rise up to speak to defend their homes, their children, their husbands or the interests of other women – women may, in extreme circumstances, speak up publicly to defend their own sectional interests, but not speak for men or the community as a whole.

Here is the thing: in the old days, public speaking and oratory were considered exclusive practices and skills that defined masculinity as a gender. “Public speech was a – if not the– defining attribute of maleness. A woman speaking in public was, in most circumstances, by definition not a woman,” stresses Beard. She highlights, “an integral part of growing up, as a man, is learning to take control of public utterance and to silence the female of the species.”

Transferring this to these days, Beard explains that “these attitudes, assumptions and prejudices are hard-wired into us: not into our brains (...) but into our culture, our language and millennia of our history.” And this plays out – still on the 21st century – not only in the overall public sphere of politics, media, etc., but also and outrageously in online spaces. “Some of these same issues of voice and gender have to do with internet trolls, death-threats and abuse. (...) What is clear is that many more men than women are the perpetrators of this stuff, and they attack women far more than they attack men (one academic study put the ratio at something like 30 to 1, female to male targets),” states Beard.

The more Beard looked at the threats and insults that women received, the more she found that they fitted into the old patterns exposed before. When venturing “into traditional male territory” being a woman, the abuse comes no matter what. “It’s not what you say that prompts it, it’s the fact you’re saying it.” And that matches the details of the threats themselves, she adds: “They include a fairly predictable menu of rape, bombing, murder and so forth.”

“Shut up you bitch” (one of the usual online messages received by women), “I’m going to cut off your head and rape it” (a tweet message that Beard herself received), or “You should have your tongue ripped out” (as tweeted out to another journalist) are just daily examples of the level of hateful messages and online threats that women receive just for the sake of speaking out in online media.

When it comes to strategies for women dealing with this kind of abuse, solutions are far from unambiguous and straightforward. One of the usual responses and consequences of the attacks is that women withdraw from the online spaces, silencing themselves. “Ironically the well-meaning solution often recommended when women are on the receiving end of this stuff turns out to bring about the very result the abusers want: namely, their silence. ‘Don’t call the abusers out. Don’t give them any attention; that’s what they want. Just keep mum,’ you’re told, which amounts to leaving the bullies in unchallenged occupation of the playground,” says Beard.

But then I came to realise, after reading about this whole continuum of culturally and politically based attempts to suppress women's voices – whether they were being excluded from the Greek agora or now from the internet agora – that there is a huge disconnect between the inherited socio-cultural and political perception of women speaking in public and the international legislative framing that gives women the fundamental right to freedom of expression, protected by international human rights law. And this is something basic, something that was fought for, which ancient civilizations lacked: the recognition of women as citizens with the same rights as men.

So this raises the question: How can our cultural patterns shift in a way that they reflect the overall advances achieved in legislation? Perhaps the answer resides close to what what Beard says: “What we need is some old fashioned consciousness-raising about what we mean by the voice of authority and how we’ve come to construct it.” Until we reach that point of awareness, we, dear women, need to continue to speak up.

Image by Harald Groven used under Creative Commons license.

Responses to this post

I guess I always think of fighting fire with fire. But I’m a guy.

To the idiotic comment about ripping open your neck, reply with more violence and idiocy. “Well, great. I have a bear trap installed in my neck to rip your weenie off. And it’s the small size, so it ought to fit you.”

To insult a guy, you often target either their penis or their sex life. If they talk about your boobs, say something like “Better than the piece of plywood you were porking last night”. If they call you a slut, say “At least I HAVE a sex life.” Typically these guys are hetero and insecure about their masculinity so calling them gay also works. If they brag about how big their dick is, reply “I bet your boyfriends like that a lot!”

Don’t just deny it with a superior air, you’ll come off as one of their teachers (probably a lot of them are school age). You have to come up with something colorful. Go to urbandictionary.com and study up on crude slang phrases like “dick cheese” and “queef” and “aunt flo”.

- Add new comment

- 10755 views

Add new comment